Government Watchdog Expects Medicaid Work Requirement Analysis by Fall

The country’s top nonpartisan government watchdog has confirmed it is examining the costs of running the nation’s only active Medicaid work requirement program, as Republican state and federal lawmakers consider similar requirements. The U.S. Government Accountability Office told KFF Health News that its analysis of […]

Health Care

Covered California Pushes for Better Health Care as Federal Spending Cuts Loom

Faced with potential federal spending cuts that threaten health coverage and falling childhood vaccination rates, Monica Soni, the chief medical officer of Covered California, has a lot on her plate — and on her mind. California’s Affordable Care Act health insurance exchange covers nearly 2 […]

Health Care

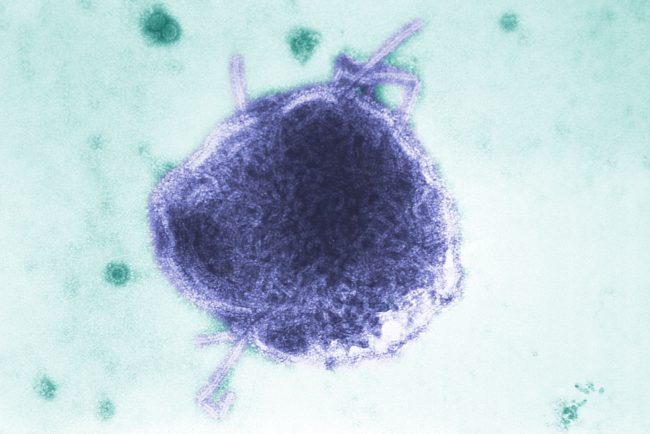

‘Sharp rise’ in Ontario measles cases with 223 new infections

Public Health Ontario is reporting 223 new measles cases since last week as the spread in its southwestern region grows.

Measles

New York warns travellers about Canada: ‘Measles is just a car ride away!’

As measles cases continue to rise in Canada, particularly in Ontario, one U.S. state is taking notice of the surge and warning its residents about travel.

MeaslesAs measles cases continue to rise in Canada, particularly in Ontario, one U.S. state is taking notice of the surge and warning its residents about travel.

Rural Hospitals Question Whether They Can Afford Medicare Advantage Contracts

Rural hospital leaders are questioning whether they can continue to afford to do business with Medicare Advantage companies, and some say the only way to maintain services and protect patients is to end their contracts with the private insurers. Medicare Advantage plans pay hospitals lower […]

Health CareRural hospital leaders are questioning whether they can continue to afford to do business with Medicare Advantage companies, and some say the only way to maintain services and protect patients is to end their contracts with the private insurers.

Medicare Advantage plans pay hospitals lower rates than traditional Medicare, said Jason Merkley, CEO of Brookings Health System in South Dakota. Merkley worried the losses would spark staff layoffs and cuts to patient services. So last year, Brookings Health dropped all four contracts it had with major Medicare Advantage companies.

“I’ve had lots of discussions with CEOs and executive teams across the country in regard to that,” said Merkley, whose health system operates a hospital and clinics in the small city of Brookings and surrounding rural areas.

Merkley and other rural hospital operators in recent years have enumerated a long list of concerns about the publicly funded, privately run health plans. In addition to the reimbursement issue, their complaints include payment delays and a resistance to authorizing patient care.

But rural hospitals abandoning their Medicare Advantage contracts can leave local patients without nearby in-network providers or force them to scramble to switch coverage.

Medicare is the main federal health insurance program for people 65 or older. Participants can enroll in traditional, government-run Medicare or in a Medicare Advantage plan run by a private insurance company.

In 2024, 56% of urban Medicare recipients were enrolled in a private plan, according to a report by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, a federal agency that advises Congress. While just 47% of rural recipients enrolled in a private plan, Medicare Advantage has expanded more quickly in rural areas.

In recent years, average Medicare Advantage reimbursements to rural hospitals were about 90% of what traditional Medicare paid, according to a new report from the American Hospital Association. And traditional Medicare already pays hospitals much less than private plans, according to a recent study by Rand Corp., a research nonprofit.

Carrie Cochran-McClain, chief policy officer at the National Rural Health Association, said Medicare Advantage is particularly challenging for small rural facilities designated critical access hospitals. Traditional Medicare pays such hospitals extra, but the private insurance companies aren’t required to do so.

“The vast majority of our rural hospitals are not in a position where they can take further cuts to payment,” Cochran-McClain said. “There are so many that are just really in a precarious financial spot.”

Nearly 200 rural hospitals have ended inpatient services or shuttered since 2005.

Mehmet Oz — doctor, former talk show host, and newly confirmed head of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services — has promoted and worked for the private Medicare industry and called for “Medicare Advantage for all.” But during his recent confirmation hearing, he called for more oversight as he acknowledged bipartisan concerns about the plans’ cost to taxpayers and their effect on patients.

Cochran-McClain said some Republican lawmakers want to address these issues while supporting Medicare Advantage.

“But I don’t think we’ve seen enough yet to really know what direction that’s all going to take,” she said.

Medicare Advantage plans can offer lower premiums and out-of-pocket costs for some participants. Nearly all offer extra benefits, such as vision, hearing, and dental coverage. Many also offer perks, such as gym memberships, nutrition services, and allowances for over-the-counter health supplies.

But a recent study in the Health Services Research journal found that rural patients on private plans struggled to access and afford care more often than rural enrollees on traditional Medicare and urban participants in both kinds of plans.

Susan Reilly, a spokesperson for the Better Medicare Alliance, said a recent report published by her group, which promotes Medicare Advantage, found that private plans are more affordable than traditional Medicare for rural beneficiaries. That analysis was conducted by an outside firm and based on a government survey of Medicare recipients.

Reilly also pointed to a study in The American Journal of Managed Care that found the growth of private plans in rural areas from 2008-2019 was associated with increased financial stability for hospitals and a reduced risk of closure.

Merkley said that’s not what he’s seeing on the ground in rural South Dakota.

He said traditional Medicare reimbursed Brookings Health System 91 cents for every dollar it spent on care in 2023, while Medicare Advantage plans paid 76 cents per dollar spent. He said his staff tried negotiating better contracts with the big Medicare Advantage companies, to no avail.

Patients who remain on private plans that no longer contract with their local hospitals and clinics may face higher prices unless they travel to in-network facilities, which in rural areas can be hours away. Merkley said most patients at Brookings Health switched to traditional Medicare or to regional Medicare Advantage plans that work better with the hospital system.

But switching from private to traditional Medicare can be unaffordable for patients.

That’s because in most states, Medigap plans — supplemental plans that help people on traditional Medicare cover out-of-pocket costs — can deny coverage or base their prices on patients’ medical history if they switch from a private plan.

Some rural health systems say they no longer work with any Medicare Advantage companies. They include Great Plains Health, which serves parts of rural Nebraska, Kansas, and Colorado, and Kimball Health Services, which is based in two small towns in Nebraska and Wyoming.

Medicare Advantage plans often limit the providers patients can see and require referrals and prior authorization for certain services. Requesting referrals, seeking preauthorization, and appealing denials can delay treatment for patients while adding extra work for doctors and billing staff.

“The unique rural lens on that is that rural providers really tend to be pretty bare-bone shops,” Cochran-McClain said. “That kind of administrative burden pulls people away from really being able to focus on providing quality care to their beneficiaries.”

Jonathon Green, CEO of Taylor Health Care Group in rural Georgia, said his system had to set up a team to deal solely with coverage denials, mostly from Medicare Advantage companies. He said some plans frequently decline to authorize payments before treatments, refuse to cover services they already approved, and deny payment for care that shouldn’t need approval.

In these cases, Green said, the companies argue that the care wasn’t appropriate for the patient.

“We hear that term constantly — ‘It’s not medically necessary,’” he said. “That’s the catchall for everything.”

Green said Taylor Health Care Group has considered dropping its Medicare Advantage contracts but is keeping them for now.

Cochran-McClain said her group supports policy changes, such as a federal bill that aims to streamline prior authorization while requiring Medicare Advantage companies to share data about the process. The 2024 bill was co-sponsored by more than half of U.S. senators, but needs to be reintroduced this year.

Cochran-McClain said rural-health advocates also want the government to require private plans to pay critical access hospitals and similar rural facilities as much as they would receive from traditional Medicare.

Green and Merkley stressed that they aren’t against the concept of private Medicare plans; they just want them to be fairer to rural facilities and patients.

Green said rural and independent hospitals don’t have the leverage that urban hospitals and large chains do in negotiations with giant Medicare Advantage companies.

“We just don’t have the ability to swing the pendulum enough,” he said.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Blockbuster Deal Will Wipe Out $30 Billion in Medical Debt. Even Backers Say It’s Not Enough.

Underscoring the massive scale of America’s medical debt problem, a New York-based nonprofit has struck a deal to pay off old medical bills for an estimated 20 million people. Undue Medical Debt, which buys patient debt, is retiring $30 billion worth of unpaid bills in […]

Health CareUnderscoring the massive scale of America’s medical debt problem, a New York-based nonprofit has struck a deal to pay off old medical bills for an estimated 20 million people.

Undue Medical Debt, which buys patient debt, is retiring $30 billion worth of unpaid bills in a single transaction with Pendrick Capital Partners, a Virginia-based debt trading company. The average patient debt being retired is $1,100, according to the nonprofit, with some reaching the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The deal will prevent the debt being sold and protect millions of people from being targeted by collectors. But even proponents of retiring patient debt acknowledge that these deals cannot solve a crisis that now touches around 100 million people in the U.S.

“We don’t think that the way we finance health care is sustainable,” Undue Medical Debt chief executive Allison Sesso said in an interview with KFF Health News. “Medical debt has unreasonable expectations,” she said. “The people who owe the debts can’t pay.”

In the past year alone, Americans borrowed an estimated $74 billion to pay for health care, a nationwide West Health-Gallup survey found. And even those who benefit from Undue’s debt relief may have other medical debt that won’t be relieved.

This large purchase also highlights the challenges that debt collectors, hospitals, and other health care providers face as patients rack up big bills that aren’t covered by their health insurance.

Pendrick’s chief executive, Chris Eastman, declined several requests to be interviewed about the debt sale, which has not been previously reported. But Eastman acknowledged in a 2024 podcast episode that collecting medical debts has grown more challenging as regulators have restricted how collectors can pursue patients.

Pendrick has now shuttered, which Sesso said provided strong motivation for this deal. “This was a really great opportunity to get a debt buyer out of the market,” she said.

Undue Medical Debt pioneered its debt relief strategy a decade ago, leveraging charitable donations to buy medical debt from debt trading companies at steeply discounted prices and then freeing patients from the obligation to pay.

The nonprofit now buys debts directly from hospitals, as well. And it is working with about two dozen state and local governments to leverage public money to relieve medical debt in communities from Los Angeles County to Cleveland to the state of Connecticut.

The approach has been controversial. And Undue Medical Debt’s record-setting purchase — financed by a mix of philanthropy and taxpayer dollars — is likely to stoke more debate over the value of paying collectors for medical debts.

“The approach is just treating the symptoms and not the disease,” said Elisabeth Benjamin, a vice president at the Community Service Society of New York, a nonprofit that has led efforts to restrict aggressive hospital collections. Benjamin and other advocates say systemic changes such as ensuring hospitals offer sufficient financial aid to patients and reining in high medical prices would be more valuable in preventing people from sinking into debt.

But many government officials see retiring people’s unpaid medical bills as part of a larger strategy to make it easier for patients to avoid debt in the first place.

“Turning off the tap is what’s really important in the long run,” said Naman Shah, a physician who directs medical affairs at the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. The county is working to improve local hospital financial aid programs for patients. But Shah said debt relief is key, as well.

“It’s easy to criticize band-aids when you’re not the one who’s cut,” he said. “As a physician, I take care of people who have cuts, and I know the importance of stitching them back up.”

Undue Medical Debt’s latest deal, which it is spending $36 million to close, will help patients nationwide, according to the nonprofit. But about half the estimated 20 million people whose debts Pendrick owned live in just two states: Texas or Florida.

Neither has expanded Medicaid coverage through the 2010 Affordable Care Act, a key tool that researchers have found bolsters patients’ financial security by protecting them from big medical bills and debt.

The patients eligible for debt relief have incomes at or below four times the federal poverty level, about $63,000 for a single person, or debts that exceed 5% of their incomes.

About half the debts are also more than seven years old. These have been donated to Undue Medical Debt by Pendrick, the group reported.

The nonprofit plans to pay for the rest of the debts over the next year and a half, though all collections have stopped against patients. It also plans to spend an additional $40 million — or $2 a person — to process the debts, find patients, and inform them that their debts have been relieved.

Sesso, Undue’s chief executive, said she hopes the debt purchase will keep policymakers focused on enacting longer-term solutions to the nation’s medical debt crisis.

She applauded state leaders for taking steps to bar medical debts from their residents’ credit scores. But she said action is also needed in Washington, D.C. However, the Trump administration has suspended regulations enacted under former President Joe Biden that would have barred credit reporting of medical debt nationally, and congressional Republicans are now moving to revoke the new rules.

“There is a limit to what state and local governments can do to solve this problem,” Sesso said. “It’s really a national problem that has to be solved at the national level.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

The House Speaker’s Eyeing Big Cuts to Medicaid. In His Louisiana District, It’s a Lifeline.

MANSFIELD, La. — When Desoto Regional Health System took out $36 million in loans last year to renovate a rural hospital that opened in 1952, officials were banking on its main funding source remaining stable: Medicaid, the joint federal-state health program for low-income people and […]

Health CareMANSFIELD, La. — When Desoto Regional Health System took out $36 million in loans last year to renovate a rural hospital that opened in 1952, officials were banking on its main funding source remaining stable: Medicaid, the joint federal-state health program for low-income people and the disabled.

But those dollars are now in jeopardy, as President Donald Trump and the GOP-controlled Congress move to shrink the nearly $900 billion health program that covers more than 1 in 5 Americans.

Desoto CEO Todd Eppler said Medicaid cuts could make it harder for his hospital to repay the loans and for patients to access care.

“I just hope that the people who are making these decisions have thought deeply about it and have some context of the real-world implications,” he said, “because it’s going to affect us as a hospital and going to affect our patients.”

One of the decision-makers is Eppler’s representative in Congress: House Speaker Mike Johnson, who lives about 35 miles north of here. He said he knows the Republican leader and his staff understand hospitals’ plight: The mother of Johnson’s chief of staff is CEO of a rural hospital in the district.

“I’ve never met a congressman yet that wanted a rural hospital in their district to close, and certainly Mike is no exception to that rule,” Eppler said.

Last year nearly 290,000 people in Johnson’s district were enrolled in Medicaid, about 38% of the total population, according to data compiled by KFF, the health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

About 118,000 of them are in the program thanks to the Affordable Care Act, which allowed states including Louisiana to expand Medicaid to cover low-income adults, many of whom were working in low-paying jobs that don’t provide health insurance.

Louisiana ranks second in Medicaid enrollment, at nearly 32% — a reflection of the state’s high poverty rate. As Republicans weigh cuts, their actions could have dramatic consequences for their constituents here. Of the eight GOP-held House districts with the most Medicaid enrollees due to the expansion, four are in Louisiana. Johnson’s largely rural district ranks sixth in expansion enrollees.

Among them is Chloe Stovall, 23, who works in the produce aisle at the SuperValu grocery store in Vivian, Louisiana. She said her take-home wage working full time is $200 a week. She doesn’t own a car and walks a mile to work.

The store provides health coverage, but she said she won’t qualify until she’s worked there for a full year — and even then, it will cost more than Medicaid, which is free.

“I’m just barely surviving,” she said.

In February, Johnson pushed a budget resolution through the House that calls for cutting at least $880 billion over a decade from a pool of funding that includes Medicaid, to help fund an extension of Trump’s tax cuts and his border priorities. Republicans in Congress are now considering where to make cuts, and Medicaid is likely to take a big hit.

Defending the plan, Johnson said that Medicaid is “not for 29-year-old males sitting on their couches playing video games.”

Stovall said almost everyone she knows on Medicaid works at least one job. “I don’t even own a TV,” she said.

Contacted for comment, Johnson’s office pointed to his remarks at a conference in Washington last month. “We’re going to be very careful not to cut a benefit for anyone who is eligible to receive it and relies upon it,” Johnson said.

KFF Health News spoke with two dozen Medicaid enrollees in Johnson’s district. Most said they were unaware their congressman is leading the Republican charge to upend the program. Those informed of the Republican plan said it scares them.

Some GOP members of Congress want to eliminate the ACA’s Medicaid expansion funding, which led to 20 million working-age adults gaining coverage and helped slash the nation’s uninsured rate to its lowest level in history. Forty states and the District of Columbia have agreed to the change, which promised extra federal funding in exchange for expanding eligibility.

In this heavily Republican district, where Johnson won with 86% of the vote in November, 22% of residents live in poverty.

Like Trump, Johnson says he wants cuts to Medicaid but hasn’t elaborated other than saying the program should not cover “able-bodied” adults without imposing a work requirement.

“Everybody is committed” to preserving Medicaid benefits “for those who desperately need it and deserve it and qualify for it,” Johnson said at a news conference in February. “What we’re talking about is rooting out the fraud, waste, and abuse.”

Medicaid recipients in Johnson’s district, told about GOP plans to cut the program, said their lives are hard enough in a state where the minimum wage is $7.25 an hour. Without Medicaid, they said, they couldn’t afford health coverage.

In Vivian, near the borders with Arkansas and Texas, close to half of the 2,900 residents live in poverty. The main-street shops are mostly shuttered, except for a thrift store and a mom-and-pop restaurant that specializes in fried pork chops.

“Most everybody you know is on Medicaid here,” said Doris Luccous, 24.

Luccous said she makes $250 a week after taxes as a housekeeper at a nursing home while raising her 2-year-old daughter in her childhood home. While shopping with her father — who doesn’t work, because of a disability — she said she counts on Medicaid for her bipolar medicines and to pay for therapy appointments.

“I don’t know where I would be without it,” she said.

Neither Luccous nor Stovall said they voted in the last election, and neither knew that Johnson is their representative in Congress.

Vivian has few large employers, and most employers pay the minimum wage, which hasn’t changed since 2009. “We are just stuck,” Stovall said.

Still, she said, “it’s a community where everybody knows everybody, and people are always willing to lend a hand because so many are in difficult financial circumstances.”

Willie White is CEO of David Raines Community Health Centers, which operates six outpatient clinics in northwestern Louisiana that serve primarily Medicaid enrollees. He said that Louisiana already ranks among the worst states for people’s health and that Medicaid cuts would only worsen the situation.

“You cannot expect health outcomes to improve if people can’t afford to access care,” White said.

While the clinics provide primary and dental care on a sliding fee scale for uninsured patients, signing them up for Medicaid gives them better access to specialists and brings the health centers revenue to cover the cost of delivering care.

Many of the centers’ patients gained coverage through Medicaid expansion. Afterward, rates of screenings for colon and cervical cancer went from 10% to 50%, White said.

But if Congress cuts Medicaid, the health centers would be forced to cut services, he said.

“Mike Johnson has been here and knows us, and he and his office have been responsive about our issues,” White said. “The message in prior years was, ‘We need additional funding,’ but now it is asking for no cuts.”

Community health centers, which in 2023 provided care nationally to more than 32 million mostly low-income people, have seen funding increases from Republicans and Democrats for decades.

“Everyone is supportive, but the question remains what that support will look like under the current administration,” White said. “If there are to be reductions, they need to be done with a scalpel.”

Expecting cuts, the health centers have already restricted travel and put a hold on filling vacant positions, White said.

Sitting in a David Raines clinic in Bossier City, Benjamin Andrade, 57, said having Medicaid has been a lifesaver since he needed heart surgery in 2020. Andrade is a chef and said he supports his wife and two children on $14 an hour.

He had not heard about any potential cuts to the program. Without Medicaid, he said, “it would be very hard for me to pay for all the medicines I take.”

Dominique Youngblood, 31, who was at the clinic for a dental checkup, said she’s had Medicaid most of her life. “Medicaid helps me so I don’t have to pay out-of-pocket going to the doctors,” she said.

Youngblood, who has two children, makes $12 an hour at a day care center. Asked about GOP efforts to scale back the program, she said, “It’s not fair, because it helps a lot of people who cannot afford medications and emergency room trips, and those are costs you can’t control.”

Back in Mansfield, Eppler’s hospital is more than just a health facility — it’s where many people in town come for lunch. The cafeteria was packed on a recent Friday as workers served boiled shrimp, fried okra, and baked fish.

Eppler said he’s aware Republicans in Congress are targeting a system of taxes that some states, including Louisiana, levy on hospitals and other health providers to draw down more federal Medicaid funding. That money helps finance what are known as supplemental payments to providers. Some conservatives belittle the extra funding as “money laundering.”

But that money accounts for about 15% of the DeSoto health system’s budget, said Eppler, a retired Air Force lieutenant colonel who has been CEO for a dozen years. “We are using that money to invest in the next 50 years of Desoto Parish, to build a hospital that they can have that will be sustainable,” he said.

The supplemental payments, for example, help pay to provide mental health services at three outpatient clinics. “If that $4 million went away, we would have to limit services — it’s just that simple,” he said.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Measles can ‘erase’ your immune system’s memory. Here’s how

Measles doesn’t just cause illness, but also erases the immune system’s memory, leaving people vulnerable to infections they’ve previously fought off.

MeaslesMeasles doesn’t just cause illness, but also erases the immune system’s memory, leaving people vulnerable to infections they’ve previously fought off.

Immigration Crackdowns Disrupt the Caregiving Industry. Families Pay the Price.

Alanys Ortiz reads Josephine Senek’s cues before she speaks. Josephine, who lives with a rare and debilitating genetic condition, fidgets her fingers when she’s tired and bites the air when something hurts. Josephine, 16, has been diagnosed with tetrasomy 8p mosaicism, severe autism, severe obsessive-compulsive […]

Health CareAlanys Ortiz reads Josephine Senek’s cues before she speaks. Josephine, who lives with a rare and debilitating genetic condition, fidgets her fingers when she’s tired and bites the air when something hurts.

Josephine, 16, has been diagnosed with tetrasomy 8p mosaicism, severe autism, severe obsessive-compulsive disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, among other conditions, which will require constant assistance and supervision for the rest of her life.

Ortiz, 25, is Josephine’s caregiver. A Venezuelan immigrant, Ortiz helps Josephine eat, bathe, and perform other daily tasks that the teen cannot do alone at her home in West Orange, New Jersey. Over the past 2½ years, Ortiz said, she has developed an instinct for spotting potential triggers before they escalate. She closes doors and peels barcode stickers off apples to ease Josephine’s anxiety.

But Ortiz’s ability to work in the U.S. has been thrown into doubt by the Trump administration, which ordered an end to the temporary protected status program for some Venezuelans on April 7. On March 31, a federal judge paused the order, giving the administration a week to appeal. If the termination goes through, Ortiz would have to leave the country or risk detention and deportation.

“Our family would be gutted beyond belief,” said Krysta Senek, Josephine’s mother, who has been trying to win a reprieve for Ortiz.

Americans depend on many such foreign-born workers to help care for family members who are older, injured, or disabled and cannot care for themselves. Nearly 6 million people receive personal care in a private home or a group home, and about 2 million people use these services in a nursing home or other long-term care institution, according to a Congressional Budget Office analysis.

Increasingly, the workers who provide that care are immigrants such as Ortiz. The foreign-born share of nursing home workers rose three percentage points from 2007 to 2021, to about 18%, according to an analysis of census data by the Baker Institute for Public Policy at Rice University in Houston.

And foreign-born workers make up a high share of other direct care providers. More than 40% of home health aides, 28% of personal care workers, and 21% of nursing assistants were foreign-born in 2022, compared with 18% of workers overall that year, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

That workforce is in jeopardy amid an immigration crackdown President Donald Trump launched on his first day back in office. He signed executive orders that expanded the use of deportations without a court hearing, suspended refugee resettlements, and more recently ended humanitarian parole programs for nationals of Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela.

In invoking the Alien Enemies Act to deport Venezuelans and attempting to revoke legal permanent residency for others, the Trump administration has sparked fear that even those who have followed the nation’s immigration rules could be targeted.

“There’s just a general anxiety about what this could all mean, even if somebody is here legally,” said Katie Smith Sloan, president of LeadingAge, a nonprofit representing more than 5,000 nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and other services for aging patients. “There’s concern about unfair targeting, unfair activity that could just create trauma, even if they don’t ultimately end up being deported, and that’s disruptive to a health care environment.”

Shutting down pathways for immigrants to work in the United States, Smith Sloan said, also means many other foreign workers may go instead to countries where they are welcomed and needed.

“We are in competition for the same pool of workers,” she said.

Growing Demand as Labor Pool Likely To Shrink

Demand for caregivers is predicted to surge in the U.S. as the youngest baby boomers reach retirement age, with the need for home health and personal care aides projected to grow about 21% over a decade, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Those 820,000 additional positions represent the most of any occupation. The need for nursing assistants and orderlies also is projected to grow, by about 65,000 positions.

Caregiving is often low-paying and physically demanding work that doesn’t attract enough native-born Americans. The median pay ranges from about $34,000 to $38,000 a year, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and home health agencies have long struggled with high turnover rates and staffing shortages, Smith Sloan said, and they now fear that Trump’s immigration policies will choke off a key source of workers, leaving many older and disabled Americans without someone to help them eat, dress, and perform daily activities.

With the Trump administration reorganizing the Administration for Community Living, which runs programs supporting older adults and people with disabilities, and Congress considering deep cuts to Medicaid, the largest payer for long-term care in the nation, the president’s anti-immigration policies are creating “a perfect storm” for a sector that has not recovered from the covid-19 pandemic, said Leslie Frane, an executive vice president of the Service Employees International Union, which represents nursing facility workers and home health aides.

The relationships caregivers build with their clients can take years to develop, Frane said, and replacements are already hard to find.

In September, LeadingAge called for the federal government to help the industry meet staffing needs by raising caps on work-related immigration visas, expanding refugee status to more people, and allowing immigrants to test for professional licenses in their native language, among other recommendations.

But, Smith Sloan said, “There’s not a lot of appetite for our message right now.”

The White House did not respond to questions about how the administration would address the need for workers in long-term care. Spokesperson Kush Desai said the president was given “a resounding mandate from the American people to enforce our immigration laws and put Americans first” while building on the “progress made during the first Trump presidency to bolster our healthcare workforce and increase healthcare affordability.”

Refugees Fill Nursing Home Jobs in Wisconsin

Until Trump suspended the refugee resettlement program, some nursing homes in Wisconsin had partnered with local churches and job placement programs to hire foreign-born workers, said Robin Wolzenburg, a senior vice president for LeadingAge Wisconsin.

Many work in food service and housekeeping, roles that free up nurses and nursing assistants to work directly with patients. Wolzenburg said many immigrants are interested in direct care roles but take on ancillary roles because they cannot speak English fluently or lack U.S. certification.

Through a partnership with the Wisconsin health department and local schools, Wolzenburg said, nursing homes have begun to offer training in English, Spanish, and Hmong for immigrant workers to become direct care professionals. Wolzenburg said the group planned to roll out training in Swahili soon for Congolese women in the state.

Over the past 2½ years, she said, the partnership helped Wisconsin nursing homes fill more than two dozen jobs. Because refugee admissions are suspended, Wolzenburg said, resettlement agencies aren’t taking on new candidates and have paused job placements to nursing homes.

Many older and disabled immigrants who are permanent residents rely on foreign-born caregivers who speak their native language and know their customs. Frane with the SEIU noted that many members of San Francisco’s large Chinese American community want their aging parents to be cared for at home, preferably by someone who can speak the language.

“In California alone, we have members who speak 12 different languages,” Frane said. “That skill translates into a kind of care and connection with consumers that will be very difficult to replicate if the supply of immigrant caregivers is diminished.”

The Ecosystem a Caregiver Supports

Caregiving is the kind of work that makes other work possible, Frane said. Without outside caregivers, the lives of the patient and their loved ones become more difficult logistically and economically.

“Think of it like pulling out a Jenga stick from a Jenga pile, and the thing starts to topple,” she said.

Thanks to the one-on-one care from Ortiz, Josephine has learned to communicate when she’s hungry or needs help. She now picks up her clothes and is learning to do her own hair. With her anxiety more under control, the violent meltdowns that once marked her weeks have become far less frequent, Ortiz said.

“We live in Josephine’s world,” Ortiz said in Spanish. “I try to help her find her voice and communicate her feelings.”

Ortiz moved to New Jersey from Venezuela in 2022 as part of an au pair program that connects foreign-born workers with people who are older or children with disabilities who need a caregiver at home. Fearing political unrest and crime in her home country, she got temporary protected status when her visa expired last year to keep her authorization to work in the United States and stay with Josephine.

Losing Ortiz would upend Josephine’s progress, Senek said. The teen would lose not only a caregiver, but also a sister and her best friend. The emotional impact would be devastating.

“You have no way to explain to her, ‘Oh, Alanys is being kicked out of the country, and she can’t come back,’” she said.

It’s not just Josephine: Senek and her husband depend on Ortiz so they can work full-time jobs and take care of themselves and their marriage. “She’s not just an au pair,” Senek said.

The family has called its congressional representatives for help. Even a relative who voted for Trump sent a letter to the president asking him to reconsider his decision.

In the March 31 court decision, U.S. District Judge Edward Chen wrote that canceling the protection could “inflict irreparable harm on hundreds of thousands of persons whose lives, families, and livelihoods will be severely disrupted.”

‘Doing the Work That Their Own People Don’t Want To Do’

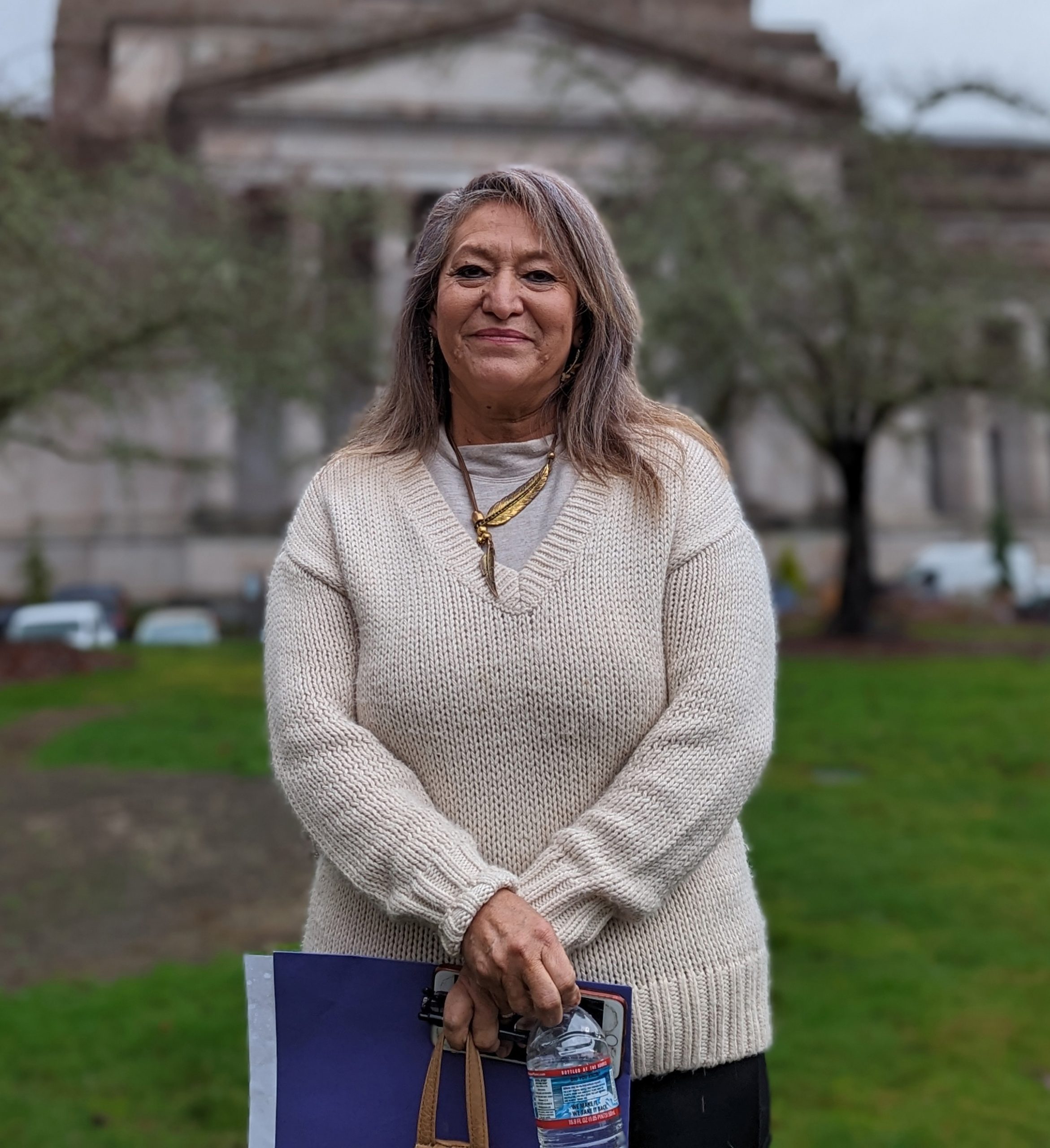

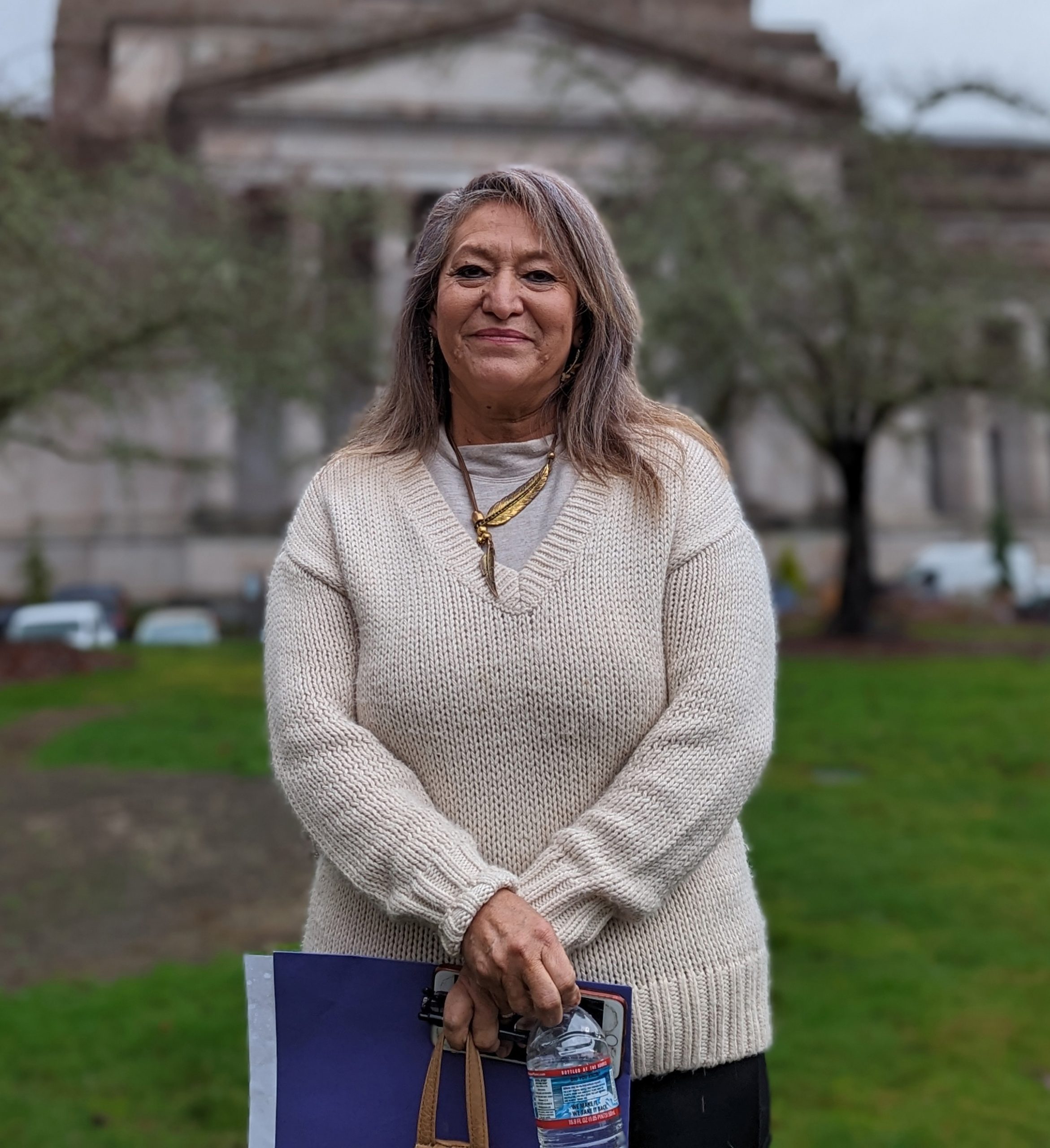

News of immigration dragnets that sweep up lawfully present immigrants and mass deportations are causing a lot of stress, even for those who have followed the rules, said Nelly Prieto, 62, who cares for an 88-year-old man with Alzheimer’s disease and a man in his 30s with Down syndrome in Yakima County, Washington.

Born in Mexico, she immigrated to the United States at age 12 and became a U.S. citizen under a law authorized by President Ronald Reagan that made any immigrant who entered the country before 1982 eligible for amnesty. So, she’s not worried for herself. But, she said, some of her co-workers working under H-2B visas are very afraid.

“It kills me to see them when they talk to me about things like that, the fear in their faces,” she said. “They even have letters, notarized letters, ready in case something like that happens, saying where their kids can go.”

Foreign-born home health workers feel they are contributing a valuable service to American society by caring for its most vulnerable, Prieto said. But their efforts are overshadowed by rhetoric and policies that make immigrants feel as if they don’t belong.

“If they cannot appreciate our work, if they cannot appreciate us taking care of their own parents, their own grandparents, their own children, then what else do they want?” she said. “We’re only doing the work that their own people don’t want to do.”

In New Jersey, Ortiz said life has not been the same since she received the news that her TPS authorization was slated to end soon. When she walks outside, she fears that immigration agents will detain her just because she’s from Venezuela.

She’s become extra cautious, always carrying proof that she’s authorized to work and live in the U.S.

Ortiz worries that she’ll end up in a detention center. But even if the U.S. now feels less welcoming, she said, going back to Venezuela is not a safe option.

“I might not mean anything to someone who supports deportations,” Ortiz said. “I know I’m important to three people who need me.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Redadas contra inmigrantes afectan a la industria del cuidado. Las familias pagan el precio.

Alanys Ortiz entiende las señales de Josephine Senek antes de que ella pueda decir nada. Josephine, quien vive con una rara y debilitante condición genética, mueve los dedos cuando está cansada y muerde el aire cuando algo le duele. Josephine tiene 16 años y ha […]

Health CareAlanys Ortiz entiende las señales de Josephine Senek antes de que ella pueda decir nada. Josephine, quien vive con una rara y debilitante condición genética, mueve los dedos cuando está cansada y muerde el aire cuando algo le duele.

Josephine tiene 16 años y ha sido diagnosticada con mosaicismo de tetrasomía 8p, autismo severo, trastorno obsesivo-compulsivo grave y trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad, entre otras afecciones. Todo esto significa que necesitará asistencia y acompañamiento constantes toda su vida.

Ortiz, de 25 años, es la cuidadora de Josephine. Esta inmigrante venezolana la ayuda a comer, bañarse y hacer tareas diarias que la adolescente no puede hacer sola en su casa en West Orange, Nueva Jersey.

Ortiz cuenta que, en los últimos dos años y medio, ha desarrollado un instinto que le permite detectar posibles factores desencadenantes de las crisis antes de que se agudicen. Por ejemplo, cierra las puertas y les quita las etiquetas de códigos de barras a las manzanas para reducir la ansiedad de Josephine.

Sin embargo, la posibilidad de trabajar en Estados Unidos puede estar en peligro para Ortiz. La administración Trump ordenó poner fin al programa de Estatus de Protección Temporal (TPS) para algunos venezolanos a partir del 7 de abril. El 31 de marzo, un juez federal suspendió la orden, dando a la administración una semana para apelar.

Si el programa se suspende, Ortiz tendrá que abandonar el país o arriesgarse a ser detenida y deportada.

“Nuestra familia quedaría devastada más allá de lo imaginable”, afirma Krysta Senek, la madre de Josephine, quien ha estado buscando un indulto para Ortiz.

Los estadounidenses dependen de muchos trabajadores nacidos en el extranjero para cuidar a sus familiares mayores, lesionados o discapacitados que no pueden valerse por sí mismos.

Según un análisis de la Oficina de Presupuesto del Congreso, casi 6 millones de personas reciben atención personal en un hogar privado o en una residencia grupal, y alrededor de 2 millones utilizan estos servicios en residencias para personas mayores u otras instituciones de cuidado a largo plazo.

Cada vez con más frecuencia, estos cuidadores son inmigrantes como Ortiz. En los centros de cuidados para adultos mayores, la proporción de trabajadores nacidos en el extranjero aumentó tres puntos porcentuales entre 2007 y 2021, hasta alcanzar aproximadamente el 18%, según un análisis de datos del Censo del Instituto Baker de Política Pública de la Universidad Rice, en Houston.

Además, los trabajadores nacidos en el extranjero representan una gran parte de otros proveedores de cuidados directos.

En 2022, más del 40% de los asistentes de salud a domicilio, el 28% de los trabajadores de cuidado personal y el 21% de los asistentes de enfermería habían nacido en el extranjero, un número superior al 18% de extranjeros en el total de la economía ese año, según datos de la Oficina de Estadísticas Laborales.

Esa fuerza laboral está en riesgo como consecuencia de la ofensiva contra los inmigrantes que Donald Trump lanzó en el primer día de su segunda administración.

El presidente firmó órdenes ejecutivas que ampliaron los casos en los que se pueden decidir las deportaciones sin audiencia judicial, suspendieron los programas de reasentamiento de los refugiados y, más recientemente, pusieron fin a los programas de permiso humanitario para ciudadanos de Cuba, Haití, Nicaragua y Venezuela.

Recurriendo a la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros para deportar a venezolanos e intentando revocar la residencia permanente de otros, la administración Trump ha generado temor incluso entre aquellos que han seguido las reglas de inmigración del país.

“Hay una ansiedad general sobre lo que esto podría significar, incluso si alguien está aquí legalmente”, dijo Katie Smith Sloan, presidenta de LeadingAge, una organización sin fines de lucro que representa a más de 5.000 residencias, hogares de cuidados asistidos y otros servicios para adultos mayores.

“Existe preocupación por la persecución injusta, por acciones que pueden ser traumáticas incluso si finalmente esas personas no terminan siendo deportadas. Pero toda esa situación, ya de por sí, altera el entorno de atención de salud”.

Según explicó Smith Sloan, cerrar las vías legales para que los inmigrantes trabajen en Estados Unidos también implica que muchos optarán por irse a países donde sí son bienvenidos y necesarios.

“Estamos compitiendo por el mismo grupo de trabajadores”, afirmó.

Más demanda, menos trabajadores

Se prevé que la demanda de trabajadores que realizan tareas de cuidado aumente considerablemente en el país, a medida que los baby boomers más jóvenes lleguen a la edad de su jubilación.

Según las proyecciones de la Oficina de Estadísticas Laborales, la necesidad de asistentes de salud y de cuidado personal a domicilio crecerá hasta cerca del 21% en el transcurso de la próxima década.

Esos 820.000 puestos adicionales representan el mayor aumento entre todas las actividades laborales. También se proyecta un crecimiento en la demanda de auxiliares de enfermería y camilleros, con un incremento de alrededor de 65.000 puestos.

El trabajo de cuidado suele ser mal remunerado y físicamente exigente, por lo que en general no atrae a suficientes estadounidenses nativos. El salario medio oscila, según la misma Oficina, entre $34.000 y $38.000 anuales.

Los hogares para adultos mayores, las residencias geriátricas con asistencia y las agencias de atención domiciliaria han lidiado durante mucho tiempo con altas tasas de rotación de personal y escasez de empleados, señaló Smith Sloan.

Ahora, además, temen que las políticas migratorias de Trump corten una fuente clave de trabajadores, dejando a muchas personas de edad avanzada, o con discapacidades, sin alguien que las ayude a comer, a vestirse y a realizar sus actividades cotidianas.

Con el gobierno de Trump reorganizando la Administración para la Vida Comunitaria —encargada de los programas que apoyan a adultos mayores y personas con discapacidades— y el Congreso considerando recortes radicales a Medicaid (el mayor financiador de cuidados a largo plazo en el país), las políticas antiinmigración del presidente están generando “la tormenta perfecta” para un sector que aún no se ha recuperado de la pandemia de covid-19, opinó Leslie Frane, vicepresidenta ejecutiva del Sindicato Internacional de Empleados de Servicios, que representa a estos trabajadores.

Frane señaló que la relación que los cuidadores construyen con sus pacientes puede tardar años en desarrollarse, y que hoy ya es muy complicado encontrar personas que los reemplacen.

En septiembre, la organización LeadingAge hizo un llamado al gobierno federal para que ayudara a la industria a cubrir sus necesidades de personal. Le propuso, entre otras recomendaciones, que aumentara los cupos de visas de inmigración relacionadas con estos trabajos, ampliara el estatus de refugiado a más personas y permitiera que los inmigrantes rindieran los exámenes de certificación profesional en su idioma nativo.

Pero, agregó Smith Sloan, “en este momento no hay mucho interés en nuestro mensaje”.

La Casa Blanca no respondió a las preguntas sobre cómo la administración abordaría la necesidad de aumentar el número de trabajadores en el sector de cuidados a largo plazo.

El vocero Kush Desai declaró que el presidente recibió “un mandato contundente del pueblo estadounidense para hacer cumplir nuestras leyes migratorias y poner a los estadounidenses en primer lugar”, al tiempo que -dijo- continúa con “los avances logrados durante la primera presidencia de Trump para fortalecer al personal del sector salud y hacer que la atención médica sea más accesible”.

En Wisconsin, refugiados trabajan con adultos mayores

Hasta que Trump suspendió el programa de reasentamiento de refugiados, en Wisconsin algunas residencias de adultos mayores se habían asociado con iglesias locales y programas de inserción laboral para contratar trabajadores nacidos en el extranjero, explicó Robin Wolzenburg, vicepresidente senior de LeadingAge Wisconsin.

Muchas de estas personas trabajan en el servicio de comidas y en la limpieza, funciones que liberan a las enfermeras y auxiliares de enfermería para que puedan atender directamente a los pacientes.

Sin embargo, Wolzenburg agregó que muchos inmigrantes están interesados en asumir funciones de atención directa, pero que se emplean en funciones auxiliares porque no hablan inglés con fluidez o no tienen una certificación válida estadounidense.

Wolzenburg contó que, a través de una asociación con el departamento de salud de Wisconsin y las escuelas locales, los hogares de adultos mayores han comenzado a ofrecer formación en inglés, español y hmong para que los trabajadores inmigrantes puedan convertirse en profesionales de atención directa.

Dijo también que el grupo planeaba impartir pronto una capacitación en swahili para las mujeres congoleñas que viven en el estado.

En los últimos dos años y medio, esta colaboración ayudó a los centros de cuidados para personas mayores de Wisconsin a cubrir más de una veintena de puestos de trabajo, dijo.

Sin embargo, Wolzenburg explicó que, por la suspensión de las admisiones de refugiados, las agencias de reasentamiento no están incorporando nuevos candidatos y han puesto una pausa a la incorporación de estos trabajadores.

Muchos inmigrantes mayores o que tienen alguna discapacidad, y a la vez son residentes permanentes, dependen de cuidadores nacidos en el extranjero que hablen su idioma y conozcan sus costumbres.

Frane, del sindicato SEIU, señaló que muchos miembros de la numerosa comunidad chino-estadounidense de San Francisco quieren que sus padres mayores reciban atención en casa, preferiblemente de alguien que hable su mismo idioma.

“Solo en California, tenemos miembros del sindicato que hablan 12 lenguas diferentes, dijo Frane. Esa habilidad se traduce en una calidad de atención y una conexión con los usuarios que será muy difícil de replicar si disminuye la cantidad de cuidadores inmigrantes”.

El ecosistema que depende del trabajo de un cuidador

Las tareas de cuidado son el tipo de trabajo que permite que otros trabajos sean posibles, sostuvo Frane. Sin cuidadores externos, la vida de los pacientes y de sus seres queridos se vuelve más difícil desde el punto de vista logístico y económico.

“Es como sacar el pilar que sostiene todo lo demás: el sistema entero tambalea”, agregó.

Gracias a la atención personalizada de Ortiz, Josephine ha aprendido a comunicar cuando tiene hambre o necesita ayuda. Ahora recoge su ropa y está comenzando a peinarse sola. Como su ansiedad está más controlada, las crisis violentas que antes solían repetirse semana tras semana se han vuelto mucho menos frecuentes, dijo Ortiz.

“Vivimos en el mundo de Josephine”, explica Ortiz en español. “Intento ayudarla a encontrar su voz y a expresar sus sentimientos”.

Ortiz llegó a Nueva Jersey desde Venezuela en 2022 a través de un programa de Au Pair para conectar trabajadores nacidos en el extranjero con personas mayores o niños con discapacidades que necesitan cuidados en su hogar.

Temerosa de la inestabilidad política y la inseguridad en su país, cuando su visa expiró obtuvo el TPS el año pasado. Quería seguir trabajando en Estados Unidos, y quedarse con Josephine.

Perder a Ortiz sería un golpe devastador para el progreso de Josephine, aseguró Senek. La adolescente no solo se quedaría sin su cuidadora, sino también sin una hermana y su mejor amiga. El impacto emocional sería enorme.

“Nosotros no tenemos ninguna manera de explicarle a Josephine que Alanys está siendo expulsada del país y que no puede volver'”, dijo Senek.

No se trata solo de Josephine: Senek y su esposo también dependen de Ortiz para poder trabajar a tiempo completo y cuidar de sí mismos y de su matrimonio. “Ella no es solo una Au Pair”, dijo Senek.

La familia ha contactado a sus representantes en el Congreso en busca de ayuda. Incluso un familiar que votó por Trump le envió una carta al presidente pidiéndole que reconsiderara su decisión.

En el fallo judicial del 31 de marzo, el juez federal Edward Chen escribió que cancelar esta protección podría “ocasionar un daño irreparable a cientos de miles de personas cuyas vidas, familias y medios de subsistencia se verán gravemente afectados”.

“Solo estamos haciendo el trabajo que su propia gente no quiere hacer”

Las noticias sobre redadas migratorias que detienen incluso a inmigrantes con estatus legal y las deportaciones masivas están generando mucho estrés, incluso entre quienes han seguido todas las reglas, comentó Nelly Prieto, de 62 años, quien cuida a un hombre de 88 con Alzheimer y a otro de unos 30 con síndrome de Down en el condado de Yakima, Washington.

Nacida en México, Prieto emigró a Estados Unidos a los 12 años y se convirtió en ciudadana estadounidense en virtud de una ley impulsada por el presidente Ronald Reagan que ofrecía amnistía a cualquier inmigrante que hubiera entrado en el país antes de 1982. Así que ella no está preocupada por sí misma. Pero, dijo, algunos de sus compañeros de trabajo con visados H-2B tienen mucho miedo.

“Me parte el alma verlos cuando me hablan de estas cosas, el miedo en sus rostros”, dijo. “Incluso tienen preparadas cartas firmadas ante un notario diciendo con quién deben quedarse sus hijos, por si algo llega a pasar”.

Los trabajadores de salud a domicilio que nacieron en el extranjero sienten que están contribuyendo con un servicio valioso a la sociedad estadounidense al cuidar de sus miembros más vulnerables, dijo Prieto. Pero sus esfuerzos se ven ensombrecidos por los discursos y las políticas que hacen que los inmigrantes se sientan como si fueran ajenos al país.

“Si no pueden apreciar nuestro trabajo, si no pueden apreciar que cuidemos de sus propios padres, de sus propios abuelos, de sus propios hijos, entonces, ¿qué más quieren?”, dijo. “Solo estamos haciendo el trabajo que su propia gente no quiere hacer”.

En Nueva Jersey, Ortiz contó que su vida no ha sido la misma desde que recibió la noticia de que su permiso bajo el TPS está por terminar. Cada vez que sale a la calle, teme que agentes de inmigración la detengan solo por ser venezolana.

Se ha vuelto mucho más precavida: siempre lleva consigo documentos que prueban que tiene autorización para vivir y trabajar en Estados Unidos.

Ortiz teme terminar en un centro de detención. Aunque Estados Unidos ahora no es un lugar acogedor, consideró que regresar a Venezuela no es una opción segura.

“Puede que yo no signifique nada para alguien que apoya las deportaciones”, dijo Ortiz. “Pero sé que soy importante para tres personas que me necesitan”.

Esta historia fue producida por Kaiser Health News, que publica California Healthline, un servicio editorialmente independiente de la California Health Care Foundation.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Saskatchewan Health Authority reports 6th measles case in province’s southwest

The most recent case was found in southwest Saskatchewan and involves an unvaccinated adult who travelled from Mexico and the United States.

MeaslesThe most recent case was found in southwest Saskatchewan and involves an unvaccinated adult who travelled from Mexico and the United States.

KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': American Health Gets a Pink Slip

The Host Julie Rovner KFF Health News @jrovner Read Julie’s stories. Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically […]

PharmaceuticalsThe Host

Julie Rovner

KFF Health News

Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically praised reference book “Health Care Politics and Policy A to Z,” now in its third edition.

The Department of Health and Human Services underwent an unprecedented purge this week, as thousands of employees from the National Institutes of Health, the FDA, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and other agencies across the department were fired, placed on administrative leave, or offered transfers to far-flung Indian Health Service facilities in such places as New Mexico, Montana, and Alaska. Altogether, the layoffs mean the federal government, in a single day, shed hundreds if not thousands of years of health and science expertise.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court heard a case about whether states can bar Planned Parenthood from providing non-abortion-related services to Medicaid patients. But by the time the case is settled, it’s unclear how much of Medicaid or the Title X Family Planning Program will remain intact.

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of KFF Health News, Rachel Cohrs Zhang of Bloomberg News, Sarah Karlin-Smith of the Pink Sheet, and Lauren Weber of The Washington Post.

Panelists

Rachel Cohrs Zhang

Bloomberg News

Sarah Karlin-Smith

Pink Sheet

Lauren Weber

The Washington Post

Among the takeaways from this week’s episode:

- As details trickle out about the major staffing purge underway at HHS, long-serving and high-ranking health officials are among those who have been shown the door: in particular, senior scientists at FDA, including the top vaccine regulator, and even the head veterinarian working on bird flu response.

- The Trump administration has also gutted entire offices, including the FDA’s tobacco division — even though the division’s elimination would not save taxpayer money because it’s not funded by taxpayers. Still, the tobacco industry stands to benefit from less regulatory oversight. Many health agencies have their own examples of federal jobs cut under the auspices of saving taxpayer money when the true effect will be undermining federal health work.

- Democratic Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey set a record this week during a marathon, 25-hour-plus chamber floor speech railing against Trump administration actions, and he used much of his time discussing the risks posed to Americans’ health care. With Republicans considering deep cuts that could hit Medicaid hard, it’s possible that health changes could be the area that resonates most with Americans and garner key support for Democrats come midterm elections.

- And the tariffs unveiled by President Donald Trump this week reportedly touch at least some pharmaceuticals, leaving the drug industry scrambling to sort out the impact. It seems likely tariffs would raise the prices Americans pay for drugs, as tariffs are expected to do for other consumer products — leaving it unclear how Americans stand to benefit from the president’s decision to upend global trade.

Also this week, Rovner interviews KFF Health News’ Julie Appleby, whose latest “Bill of the Month” feature is about a short-term health plan and a very expensive colonoscopy. Do you have a baffling, confusing, or outrageous medical bill to share with us? You can do that here.

Plus, for “extra credit,” the panelists suggest health policy stories they read this week that they think you should read, too:

Julie Rovner: Stat’s “Uber for Nursing Is Here — And It’s Not Good for Patients or Nurses,” by Katie J. Wells and Funda Ustek Spilda.

Sarah Karlin-Smith: MSNBC’s “Florida Considers Easing Child Labor Laws After Pushing Out Immigrants,” by Ja’han Jones.

Lauren Weber: The Atlantic’s “Miscarriage and Motherhood,” by Ashley Parker.

Rachel Cohrs Zhang: The Wall Street Journal’s “FDA Punts on Major Covid-19 Vaccine Decision After Ouster of Top Official,” by Liz Essley White.

Also mentioned in this week’s podcast:

- Stat’s “Laid-Off HHS Leaders Offered Transfers to Remote Indian Health Service Regions,” by Usha Lee McFarling.

- The Washington Post’s “Fired Health Workers Were Told To Contact an Employee. She’s Dead.” By Lauren Weber.

- Georgia Recorder’s “Bill That Criminalizes Abortion, Undermines IVF Access Gets Georgia House Panel Hearing,” by Jill Nolin.

Credits

Francis Ying

Audio producer

Emmarie Huetteman

Editor

To hear all our podcasts, click here.

And subscribe to KFF Health News’ “What the Health?” on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Ontario reports 89 new measles cases over a week

Ontario is reporting 89 new measles cases over the last week, bringing the province’s case count to 661 since an outbreak began in the fall.

MeaslesOntario is reporting 89 new measles cases over the last week, bringing the province’s case count to 661 since an outbreak began in the fall.