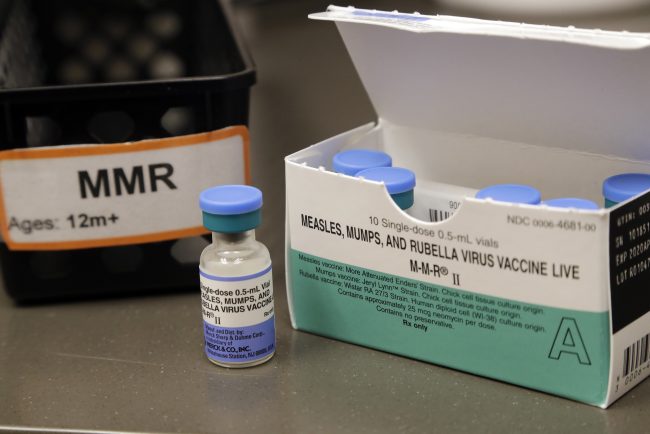

Alberta reports 17 more cases of measles, bringing total to more than 200

Measles symptoms include fever, coughing, a runny nose, red eyes and a blotchy, red rash that appears three to seven days after the fever starts.

Measles

Toronto Public Health warns of possible measles exposure at major tourist attraction

Toronto Public Health said that on Monday, April 21, someone with a case of measles had visited Ripley’s Aquarium, beside the CN Tower.

Measles

Montana Lawmakers Approve $124M To Revamp Behavioral Health System

HELENA, Mont. — Montana’s frayed behavioral health care system, still recovering from the effects of past budget cuts, will get a shot in the arm after state lawmakers approved sweeping changes to upgrade and expand facilities, increase community services, and revise commitment procedures. Lawmakers backed […]

Rural Health

Trump HHS Eliminates Office That Sets Poverty Levels Tied to Benefits for 80 Million People

President Donald Trump’s firings at the Department of Health and Human Services included the entire office that sets federal poverty guidelines, which determine whether tens of millions of Americans are eligible for health programs such as Medicaid, food assistance, child care, and other services, former […]

Health CarePresident Donald Trump’s firings at the Department of Health and Human Services included the entire office that sets federal poverty guidelines, which determine whether tens of millions of Americans are eligible for health programs such as Medicaid, food assistance, child care, and other services, former staff said.

The small team, with technical data expertise, worked out of HHS’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, or ASPE. Their dismissal mirrored others across HHS, which came without warning and left officials puzzled as to why they were “RIF’ed” — as in “reduction in force,” the bureaucratic language used to describe the firings.

“I suspect they RIF’ed offices that had the word ‘data’ or ‘statistics’ in them,” said one of the laid-off employees, a social scientist whom KFF Health News agreed not to name because the person feared further recrimination. “It was random, as far as we can tell.”

Among those fired was Kendall Swenson, who had led development of the poverty guidelines for many years and was considered the repository of knowledge on the issue, according to the social scientist and two academics who have worked with the HHS team.

The sacking of the office could lead to cuts in assistance to low-income families next year unless the Trump administration restores the positions or moves its duties elsewhere, said Robin Ghertner, the fired director of the Division of Data and Technical Analysis, which had overseen the guidelines.

The poverty guidelines are “needed by many people and programs,” said Timothy Smeeding, a professor emeritus of economics at the La Follette School of Public Affairs at the University of Wisconsin. “If you’re thinking of someone you fired who should be rehired, Swenson would be a no-brainer,” he added.

Under a 1981 appropriations bill, HHS is required annually to take Census Bureau poverty-line figures, adjust them for inflation, and create guidelines that agencies and states use to determine who is eligible for various types of help.

There’s a special sauce for creating the guidelines that includes adjustments and calculations, Ghertner said. Swenson and three other staff members would independently prepare the numbers and quality-check them together before they were issued each January.

Everyone in Ghertner’s office was told last week, without warning, that they were being put on administrative leave until June 1, when their employment would officially end, he said.

“There’s literally no one in the government who knows how to calculate the guidelines,” he said. “And because we’re all locked out of our computers, we can’t teach anyone how to calculate them.”

ASPE had about 140 staff members and now has about 40, according to a former staffer. The HHS shake-up merged the office with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, or AHRQ, whose staff has shrunk from 275 to about 80, according to a former AHRQ official who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

HHS has said it laid off about 10,000 employees and that, combined with other moves, including a program to encourage early retirements, its workforce has been reduced by about 20,000. But the agency has not detailed where it made the cuts or identified specific employees it fired.

“These workers were told they couldn’t come into their offices so there’s no transfer of knowledge,” said Wendell Primus, who worked at ASPE during the Bill Clinton administration. “They had no time to train anyone, transfer data, etc.”

HHS did not respond to a request for comment. Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has so far declined to testify about the staff reductions before congressional committees that oversee much of his agency. On April 9, a delegation of 10 Democratic members of Congress waited fruitlessly for a meeting in the agency’s lobby.

The group was led by House Energy and Commerce health subcommittee ranking member Diana DeGette (D-Colo.), who told reporters afterward that Kennedy must appear before the committee “and tell us what his plan is for keeping America healthy and for stopping these devastating cuts.”

Matt VanHyfte, a spokesperson for the Republican committee leadership, said HHS officials would meet with bipartisan committee staff on April 11 to discuss the firings and other policy issues.

ASPE serves as a think tank for the HHS secretary, said Primus, who later was Rep. Nancy Pelosi’s senior health policy adviser for 18 years. In addition to the poverty guidelines, the office maps out how much Medicaid money goes to each state and reviews all regulations developed by HHS agencies.

“These HHS staffing cuts — 20,000 — obviously they are completely nuts,” Primus said. “These were not decisions made by Kennedy or staff at HHS. They are being made at the White House. There’s no rhyme or reasons to what they’re doing.”

HHS leaders may be unaware of their legal duty to issue the poverty guidelines, Ghertner said. If each state and federal government agency instead sets guidelines on its own, it could create inequities and lead to lawsuits, he said.

And sticking with the 2025 standard next year could put benefits for hundreds of thousands of Americans at risk, Ghertner said. The current poverty level is $15,650 for a single person and $32,150 for a family of four.

“If you make $30,000 and have three kids, say, and next year you make $31,000 but prices have gone up 7%, suddenly your $31,000 doesn’t buy you the same,” he said, “but if the guidelines haven’t increased, you might be no longer eligible for Medicaid.”

The 2025 poverty level for a family of five is $37,650.

As of October, about 79 million people were enrolled in Medicaid or the related Children’s Health Insurance Program, both of which are means-tested and thus depend on the poverty guidelines to determine eligibility.

Eligibility for premium subsidies for insurance plans sold in Affordable Care Act marketplaces is also tied to the official poverty level.

One in eight Americans rely on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or food stamps, and 40% of newborns and their mothers receive food through the Women, Infants, and Children program, both of which also use the federal poverty level to determine eligibility.

Former employees in the office said they were not disloyal to the president. They knew their jobs required them to follow the administration’s objectives. “We were trying to support the MAHA agenda,” the social scientist said, referring to Kennedy’s “Make America Healthy Again” rubric. “Even if it didn’t align with our personal worldviews, we wanted to be useful.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

155 new Ontario measles cases sees total infections exceed 800

Ontario is reporting 155 new measles cases over the last week, pushing the province’s case count to 816 since an outbreak began in the fall.

MeaslesOntario is reporting 155 new measles cases over the last week, pushing the province’s case count to 816 since an outbreak began in the fall.

Tácticas migratorias de Trump obstaculizan esfuerzos para evitar una pandemia de gripe aviar, dicen investigadores

Las agresivas tácticas de deportación han aterrorizado a los trabajadores agrícolas, que son el centro de la estrategia nacional contra la gripe aviar, según afirman trabajadores de salud pública. Los trabajadores de las industrias láctea y avícola han representado la mayoría de los casos de […]

Rural HealthLas agresivas tácticas de deportación han aterrorizado a los trabajadores agrícolas, que son el centro de la estrategia nacional contra la gripe aviar, según afirman trabajadores de salud pública.

Los trabajadores de las industrias láctea y avícola han representado la mayoría de los casos de gripe aviar en el país, y prevenir y detectar los casos entre ellos es clave para evitar una pandemia. Sin embargo, los especialistas en salud pública afirman que tienen dificultades para llegar a los trabajadores agrícolas porque muchos tienen miedo de hablar con desconocidos o de salir de casa.

“La gente tiene mucho miedo de salir, incluso para comprar alimentos”, dijo Rosa Yáñez, trabajadora social de Strangers No Longer, una organización católica con sede en Detroit que apoya a inmigrantes y refugiados en Michigan con problemas legales y de salud, incluida la gripe aviar. “La gente está preocupada por perder a sus hijos, o por que sus hijos pierdan a sus padres”.

“Solía hablarle a la gente sobre la gripe aviar, y los trabajadores estaban contentos de recibir esa información”, dijo Yáñez. “Pero ahora solo quieren conocer sus derechos”.

Los trabajadores comunitarios que capacitan a los trabajadores agrícolas sobre la gripe aviar, les proporcionan equipo de protección y los conectan con las pruebas afirman haber notado un cambio drástico —primero en California, el estado más afectado por la gripe aviar— luego de las redadas de inmigración que comenzaron el 7 de enero, un día después que el Congreso certificara la victoria electoral del presidente Donald Trump.

Fue entonces cuando agentes de la Patrulla Fronteriza detuvieron indiscriminadamente a unos 200 trabajadores agrícolas y jornaleros latinos en el Valle Central de California, según informes locales citados en una demanda presentada posteriormente por la Unión Americana de Libertades Civiles (ACLU) en nombre del sindicato United Farm Workers y varias personas que fueron detenidas.

“Los agentes de la Patrulla Fronteriza se lanzaron a una expedición de pesca” en una redada de tres días llamada “Operación Devolución al Remitente” (operation Return to Sender), que “separó a familias y aterrorizó a la comunidad”, alega la demanda.

Entre las personas detenidas se encontraba Yolanda Aguilera Martínez, trabajadora agrícola y abuela que reside legalmente en Estados Unidos y no tiene antecedentes penales. Iba a una cita médica conduciendo a la velocidad límite cuando agentes vestidos de civil en vehículos sin identificación la detuvieron, le ordenaron que bajara del coche, la empujaron al suelo y la esposaron, según la demanda.

Los agentes finalmente liberaron a Aguilera Martínez, pero la demanda indica que otras personas que enfrentaban la deportación fueron detenidas durante días en “celdas frías y sin ventanas” antes de ser trasladadas a México, y abandonadas.

No se les explicó el motivo de su arresto, ni se les dio la oportunidad de defenderse, ni se les permitió llamar a un abogado ni a sus familias, alega la demanda. Indica que los cuatro hijos de un padre deportado, sin antecedentes penales, “se han vuelto silenciosos y temerosos”, y que las convulsiones de uno de los hijos con epilepsia “han empeorado”.

La noticia de la redada se difundió rápidamente en California, donde viven aproximadamente 880.000 trabajadores agrícolas, principalmente latinos. Las lecherías que emplean mano de obra inmigrante producen casi el 80% del suministro de leche de Estados Unidos, según una encuesta de 2014.

“Luego de la Operación Devolución al Remitente, los trabajadores lácteos se mostraron aún más reacios a hablar, incluso anónimamente, sobre la falta de protección en las granjas lecheras y la falta de días por enfermedad cuando se contagian”, declaró Antonio De Loera-Brust, vocero de la Unión de Trabajadores Agrícolas.

Trabajadores comunitarios en otros estados reportan un efecto intimidatorio similar debido a las redadas y las políticas migratorias aprobadas tras la toma de posesión de Trump, quien degradó repetidamente a los inmigrantes y prometió deportaciones masivas durante la campaña electoral. “No son humanos, son animales”, dijo refiriéndose a los inmigrantes que se encontraban sin autorización en Estados Unidos el pasado abril.

La primera medida legislativa de Trump fue promulgar la Ley Laken Riley, que ordena la detención federal de inmigrantes acusados de cualquier delito, independientemente de si hayan sido o no condenados.

El 20 de enero, el Departamento de Seguridad Nacional anuló la política de “áreas protegidas”, permitiendo a los agentes arrestar a personas sin papeles en escuelas, hospitales o iglesias. En marzo, la administración Trump deportó a más de 100 venezolanos y otras personas sin una audiencia previa, ignorando una orden judicial que que obligaba frenar los aviones que los trasladaban a El Salvador.

Las consecuencias para la salud pública de la desaparición de los trabajadores agrícolas son potencialmente enormes: científicos especializados en enfermedades infecciosas afirman que prevenir el contagio de gripe aviar y detectar los casos son fundamentales para prevenir una pandemia. Por eso, el gobierno ha financiado iniciativas para proteger a estos trabajadores, y monitorearlos para detectar signos de gripe aviar, como ojos rojos o síntomas similares a los de la gripe.

“Cada vez que un trabajador se enferma, juega el azar, así que protegerlo es en el interés de todos”, dijo De Loera-Brust. “Al virus no le importa lo que digan tus documentos de inmigración”.

Potencial de pandemia

Aproximadamente 65 trabajadores lácteos y de granjas de aves de corral han dado positivo para la prueba de gripe aviar desde marzo de 2024, pero el número real de infecciones es mayor. Una investigación de KFF Health News descubrió que la vigilancia deficiente provocó que casos pasaran desapercibidos en las granjas el año pasado, y estudios han revelado indicios de infecciones previas en trabajadores agrícolas que no se habían realizado la prueba.

Los departamentos de salud estatales y locales estaban empezando a superar las barreras del año pasado para las pruebas de gripe aviar, dijo Salvador Sandoval, médico que se jubiló recientemente del departamento de salud del condado de Merced, en California. Ahora, dijo, “la gente ve una unidad móvil de pruebas y piensa que es la Patrulla Fronteriza”.

El año pasado, las organizaciones de divulgación se conectaron con los trabajadores agrícolas en lugares donde se reunían, como en eventos de distribución de alimentos, pero estos ya no tienen mucha concurrencia, dijeron Sandoval y otros.

“Independientemente de su estatus migratorio, las personas con apariencia de inmigrantes sienten mucho miedo en este momento”, dijo Hunter Knapp, director de desarrollo de Project Protect Food Systems Workers, una organización de defensa de los trabajadores agrícolas en Colorado que realiza actividades de divulgación sobre la gripe aviar. Knapp explicó que algunos trabajadores de salud comunitarios latinos han reducido sus esfuerzos de divulgación por temor a ser acosados por las autoridades o el público.

Una trabajadora comunitaria latina en Michigan, que habló bajo condición de anonimato por temor a represalias contra su familia, dijo: “Mucha gente no va al médico en este momento debido a la situación migratoria”.

“Prefieren quedarse en casa y dejar que el dolor, el enrojecimiento del ojo o lo que sea desaparezca”, agregó. “La situación se ha intensificado mucho este año y la gente está muy, muy asustada”.

Los Centros para el Control y Prevención de Enfermedades (CDC) han reportado muchos menos casos humanos desde que Trump asumió el cargo. Durante los tres meses previos al 20 de enero, la agencia confirmó dos docenas de casos. Desde entonces, solo se han detectado tres, incluidas dos personas con casos lo suficientemente graves como para ser hospitalizadas.

Los CDC han afirmado que continúan monitoreando la gripe aviar, pero Jennifer Nuzzo, directora del Centro de Pandemias de la Universidad de Brown, señaló que la baja de los casos podría deberse a que se hacen menos pruebas. “Me preocupa que estemos observando una disminución en la vigilancia y no necesariamente una disminución en la propagación del virus”.

Las infecciones no detectadas representan una amenaza para los trabajadores agrícolas y para el público en general.

Dado que los virus evolucionan mutando dentro del cuerpo, cada infección es como presionar la palanca de una máquina tragamonedas. Una persona que falleció a causa de la gripe aviar en Louisiana en diciembre ilustra este punto: la evidencia científica sugiere que los virus de la gripe aviar evolucionaron dentro del paciente, generando mutaciones que podrían aumentar su capacidad de propagación entre humanos. Sin embargo, debido a que el paciente estuvo aislado en un hospital, los virus más peligrosos no se transmitieron a otros.

Esto podría no ocurrir si los trabajadores agrícolas enfermos no reciben tratamiento y viven en hogares hacinados o en centros de detención sin ventanas donde podrían infectar a otros, señaló Angela Rasmussen, viróloga de la Universidad de Saskatchewan, en Canadá.

Aunque la gripe aviar aún no se propaga fácilmente entre personas por aire, como la gripe estacional, podría diseminarse ocasionalmente cuando las personas están en espacios reducidos, y evolucionar para hacerlo con más eficiencia.

“Me preocupa que no nos demos cuenta de que esto está sucediendo hasta que algunas personas enfermen gravemente”, dijo Rasmussen. “En ese momento, las cifras serían tan altas que podrían descontrolarse”.

El virus pouede no evolucionar nunca para propagarse fácilmente, pero podría pasar. Rasmussen afirmó que el resultado sería “catastrófico”. Basándose en lo que se sabe sobre las infecciones humanas, ella y sus colegas predicen en un nuevo informe que una pandemia de gripe aviar H5N1 “colapsaría los sistemas de salud” y “causaría millones de muertes más” que la pandemia de covid-19.

Entrega de vacunas

A fines del año pasado, los CDC lanzaron una campaña de vacunación contra la gripe estacional dirigida a más de 200.000 trabajadores ganaderos. La esperanza era que la vacunación contra la gripe redujera la probabilidad de que un trabajador agrícola se infectara simultáneamente con los virus de la gripe estacional y la gripe aviar.

La coinfección permite que ambos virus intercambien genes, creando potencialmente un virus de la gripe aviar que se propagaría con la misma facilidad que la variante estacional.

Sin embargo, Sandoval afirmó que la vacunación contra la gripe disminuyó inmediatamente después del operativo de enero en California.

Funcionarios de Aduanas y Protección Fronteriza informaron en un comunicado que arrestaron a 78 inmigrantes que se encontraban “ilegalmente en Estados Unidos” durante el operativo de tres días.

Entre ellos se encontraba un delincuente sexual convicto y otras personas con antecedentes penales, como vandalismo y hurtos menores, según el comunicado. La agencia no especificó las acusaciones contra cada persona ni si todos habían sido acusados. Ex funcionarios de la administración Biden, que se encontraba en sus últimos días cuando ocurrieron los arrestos, tomarán distancia del operativo en entrevistas con Los Angeles Times.

Mayra Joachin, abogada de la ACLU del Sur de California, afirmó que el operativo era diferente a otros del gobierno de Biden, ya que se trataba de arrestos indiscriminados por parte de la Patrulla Fronteriza en el interior del país.

“Encaja con la campaña más amplia de la administración Trump de infundir miedo en las comunidades inmigrantes”, declaró, “como se vio en la campaña electoral y en acciones posteriores que atacaban a cualquiera que se percibiera como extranjero en el país”.

En marzo, David Kim, subjefe de la unidad de la Patrulla Fronteriza que dirigió el operativo, lo calificó como una “prueba de concepto”.

“Sabemos que ahora podemos superar ese límite en cuanto a distancia”, declaró al medio de comunicación del sur de California Inewsource.

El Departamento de Seguridad Nacional no respondió a las solicitudes de comentarios. En un correo electrónico, Kush Desai, vocero de la Casa Blanca, escribió: “A pesar de lo que creen los ‘expertos’, combatir la epidemia de gripe aviar y hacer cumplir nuestras leyes de inmigración no son mutuamente excluyentes”.

Anna Hill Galendez, abogada gerente del Michigan Immigrant Rights Center, entidad que participa en la difusión de información sobre la gripe aviar, afirmó que las tácticas inusualmente agresivas de los agentes del Servicio de Inmigración y Control de Aduanas (ICE) disuadieron a los trabajadores lácteos enfermos de la Península Superior de Michigan de salir de sus hogares para recibir atención médica a finales de enero. Se pusieron en contacto con el centro para solicitar ayuda.

“Querían atención médica. Querían vacunas contra la gripe. Querían [equipo de protección personal]. Querían hacerse la prueba”, declaró Hill Galendez. “Pero tenían miedo de ir a cualquier parte debido a las medidas de control migratorio”.

Lynn Sutfin, funcionaria de información pública del Departamento de Salud y Servicios Humanos de Michigan (MDHHS), respondió a las preguntas sobre la situación en la península en un correo electrónico a KFF Health News: “Los trabajadores agrícolas no aceptaron la oferta de pruebas del departamento de salud local ni del MDHHS”.

Los CDC se negaron a comentar sobre el impacto de las medidas migratorias en la labor de divulgación con trabajadores agrícolas.

Para adaptarse a la nueva realidad, Yanez ahora destaca sus consejos sobre la gripe aviar en Michigan, combinándolos con información sobre los derechos de los inmigrantes.

En Colorado, Knapp dijo que su organización está cambiando su enfoque y dejando de lado la divulgación sobre la gripe aviar en eventos donde se congregan trabajadores agrícolas, ya que esto podría percibirse como una trampa: el tipo de evento que atraería a los agentes de ICE.

Los trabajadores de divulgación que viven en las mismas comunidades que los trabajadores agrícolas también se están retirando un poco. “Como latinos, siempre nos identifican”, dijo el trabajador comunitario, quien habló bajo condición de anonimato. “Tengo una visa que me protege, pero las cosas están cambiando muy rápidamente bajo la administración Trump, y la verdad es que nada es seguro”.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Trump’s Immigration Tactics Obstruct Efforts To Avert Bird Flu Pandemic, Researchers Say

Aggressive deportation tactics have terrorized farmworkers at the center of the nation’s bird flu strategy, public health workers say. Dairy and poultry workers have accounted for most cases of the bird flu in the U.S. — and preventing and detecting cases among them is key […]

Rural HealthAggressive deportation tactics have terrorized farmworkers at the center of the nation’s bird flu strategy, public health workers say.

Dairy and poultry workers have accounted for most cases of the bird flu in the U.S. — and preventing and detecting cases among them is key to averting a pandemic. But public health specialists say they’re struggling to reach farmworkers because many are terrified to talk with strangers or to leave home.

“People are very scared to go out, even to get groceries,” said Rosa Yanez, an outreach worker at Strangers No Longer, a Detroit-based Catholic organization that supports immigrants and refugees in Michigan with legal and health problems, including the bird flu. “People are worried about losing their kids, or about their kids losing their parents.”

“I used to tell people about the bird flu, and workers were happy to have that information,” Yanez said. “But now people just want to know their rights.”

Outreach workers who teach farmworkers about the bird flu, provide protective gear, and connect them with tests say they noticed a dramatic shift — first in California, the state hit hardest by the bird flu — after immigration raids beginning on Jan. 7, the day after Congress certified President Donald Trump’s election victory. That’s when Border Patrol agents indiscriminately stopped about 200 Latino farmworkers and day laborers in California’s Central Valley, according to local reports cited in a lawsuit subsequently filed by the American Civil Liberties Union on behalf of the United Farm Workers union and several people who were stopped and detained.

“Border Patrol agents went on a fishing expedition” in a three-day raid called “Operation Return to Sender” that “tore families apart and terrorized the community,” the lawsuit alleges.

Among those stopped was Yolanda Aguilera Martinez, a farmworker and grandmother who lives legally in the U.S. and has no criminal record. She was driving at the speed limit on her way to a doctor’s appointment when plainclothes agents in unmarked vehicles pulled her over, ordered her out of the car, pushed her to the ground, and handcuffed her, the lawsuit says. Agents eventually released Aguilera Martinez, but the lawsuit says others who faced deportation were detained for days in “cold, windowless cells” before they were transported to Mexico and abandoned.

They weren’t told why they had been arrested, given an opportunity to defend themselves, or allowed to call a lawyer or their families, the lawsuit alleges. It says that the four children of one deported father, who had no criminal record, “have become quiet and scared” and that his epileptic son’s “seizures have worsened.”

News of the raid spread quickly in California, where an estimated 880,000 mainly Latino farmworkers live. Dairies that employ immigrant labor produce nearly 80% of the U.S. milk supply, according to a 2014 survey.

“After Operation Return to Sender, dairy workers became even less willing to speak about the lack of protection on dairy farms and the lack of sick pay when they’re infected — even anonymously,” said Antonio De Loera-Brust, a spokesperson for the United Farm Workers.

Outreach workers in other states report a similar chilling effect from raids and immigration policies passed after Trump took office. He repeatedly degraded immigrants and pledged mass deportations on the campaign trail. “They’re not humans, they’re animals,” he said of immigrants illegally in the U.S. last April.

Trump’s first legislative action was to sign the Laken Riley Act into law, mandating federal detention for immigrants accused of any crime, regardless of whether they’re convicted. On Jan. 20, the Department of Homeland Security rescinded the “protected areas” policy, allowing agents to arrest people who don’t have legal status while they’re in schools, churches, or hospitals. Last month, the Trump administration deported more than 100 Venezuelans and others without a hearing, ignoring a court order to turn around planes flying the men to El Salvador.

The public health ramifications of farmworkers shrinking from view are potentially massive: Infectious disease scientists say that preventing people from getting bird flu and detecting cases are critical to warding off a bird flu pandemic. That’s why the government has funded efforts to protect farmworkers and monitor them for signs of bird flu, like red eyes or flu-like symptoms.

“Every time a worker gets sick, you’re rolling the die, so it’s in everyone’s interest to protect them,” De Loera-Brust said. “The virus doesn’t care what your immigration papers say.”

Pandemic Potential

About 65 dairy and poultry workers have tested positive for the bird flu since March 2024, but the true number of infections is higher. A KFF Health News investigation found that patchy surveillance resulted in cases going undetected on farms last year, and studies have revealed signs of prior infections in farmworkers who hadn’t been tested.

State and local health departments were beginning to overcome last year’s barriers to bird flu testing, said Salvador Sandoval, a doctor who retired recently from the Merced County health department in California. Now, he said, “people see a mobile testing unit and think it’s Border Patrol.”

Last year, outreach organizations connected with farmworkers at places where they gathered, like at food distribution events, but those are no longer well attended, Sandoval and others said.

“Regardless of immigration status, people who look like immigrants are feeling a lot of fear right now,” said Hunter Knapp, the development director at Project Protect Food Systems Workers, a farmworker advocacy organization in Colorado that does bird flu outreach. He said some Latino community health workers have scaled back their outreach efforts because they worry about being harassed by the authorities or members of the public.

A Latina outreach worker in Michigan, speaking on the condition of anonymity because she’s worried about retaliation against her family, said, “Many people don’t go to the doctor right now, because of the immigration situation.”

“They prefer to stay at home and let the pain or redness in the eye or whatever it is go away,” she said. “Things have really intensified this year, and people are very, very scared.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported far fewer human cases since Trump took office. During the three months before Jan. 20, the agency confirmed two dozen cases. Since then, it’s detected only three, including two people with cases severe enough to be hospitalized.

The CDC has said it continues to track the bird flu, but Jennifer Nuzzo, director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University, said the slowdown in cases might be due to a lack of testing. “I am concerned that we are seeing a contraction in surveillance and not necessarily a contraction in the spread of the virus.”

Undetected infections pose a threat to farmworkers and to the public at large. Because viruses evolve by mutating within bodies, each infection is like a pull of a slot machine lever. A person who died of the bird flu in Louisiana in December illustrates that point: Scientific evidence suggests that bird flu viruses evolved inside the patient, gaining mutations that may make the viruses more capable of spreading between humans. However, because the patient was isolated in a hospital, the more dangerous viruses didn’t transmit to others.

That might not happen if sick farmworkers don’t receive treatment and live in crowded households or windowless detention centers where they might infect others, said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada. Although the bird flu doesn’t yet have the ability to spread easily between people through the air, like the seasonal flu, it might occasionally spread when people are in close quarters — and evolve to do so more efficiently.

“I worry that we might not figure out that this is happening until some people get severely sick,” Rasmussen said. “At that point, the numbers would be so large it could go off the rails.”

The virus might never evolve to spread easily, but it could. Rasmussen said that outcome would be “catastrophic.” Based on what’s known about human infections, she and her colleagues predict in a new report that an H5N1 bird flu pandemic “would overwhelm healthcare systems” and “cause millions more deaths” than the covid-19 pandemic.

Vaccinations Drop Off

Late last year, the CDC rolled out a seasonal flu vaccine campaign targeted at more than 200,000 livestock workers. The hope was that flu vaccinations would lessen the chance of a farmworker being infected by seasonal flu and bird flu viruses simultaneously. Co-infection gives the two flu viruses a chance to swap genes, potentially creating a bird flu virus that spreads as easily as the seasonal variety.

Yet Sandoval said flu vaccine uptake dropped immediately after the January operation in California.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials said in a statement that they arrested 78 immigrants “unlawfully present in the U.S.” during the three-day operation. They included a convicted sex offender and others with criminal histories including vandalism and petty theft, the statement said. The agency did not name allegations against each person and did not say whether all had been charged.

Former officials with the Biden administration, which was in its waning days as the arrests occurred, distanced itself from the operation in interviews with the Los Angeles Times.

Mayra Joachin, an attorney at the ACLU of Southern California, said the operation was unlike others under the Biden administration in that these were indiscriminate arrests by Border Patrol in the interior of the country. “It fits with the Trump administration’s broader campaign of instilling fear in immigrant communities,” she said, “as seen in the election campaign and in subsequent actions attacking anyone perceived to be a noncitizen in the country.”

In March, an assistant chief in the Border Patrol unit that conducted the operation, David Kim, called the operation a “proof of concept.”

“We know we can push beyond that limit now as far as distance goes,” he told the Southern California news outlet Inewsource.

The Department of Homeland Security did not respond to requests for comment. In an email, White House spokesperson Kush Desai wrote, “Despite what the ‘experts’ believe, combatting the Avian flu epidemic and enforcing our immigration laws are not mutually exclusive.”

Anna Hill Galendez, a managing attorney at the Michigan Immigrant Rights Center, which is involved in bird flu outreach, said unusually aggressive tactics by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents deterred sick dairy workers in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula from leaving their homes for care in late January. They contacted the center for help.

“They wanted medical care. They wanted flu vaccines. They wanted [personal protective equipment]. They wanted to get tested,” Hill Galendez said. “But they were afraid to go anywhere because of immigration enforcement.”

Lynn Sutfin, a public information officer at the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, responded to queries about the situation in the peninsula in an email to KFF Health News, saying, “The farmworkers did not take the local health department and MDHHS up on the testing offer.”

The CDC declined to comment on the impact of immigration actions on farmworker outreach.

To adapt to the new reality, Yanez now draws attention to her advice on the bird flu in Michigan by pairing it with information on immigrant rights. Knapp, in Colorado, said his organization is shifting its approach away from bird flu outreach at events where farmworkers congregate, because that could be perceived as a setup — and could inadvertently become one if ICE agents targeted such an event.

Outreach workers who live among farmworkers are withdrawing a little, too. “Being Latinos, we are always identified,” said the outreach worker who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “I have a visa that protects me, but things are changing very quickly under the Trump administration, and the truth is, nothing is certain.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Tax Time Triggers Fraud Alarms for Some Obamacare Enrollees

Because of past fraud by rogue brokers, some Affordable Care Act policyholders may get an unexpected tax bill this season. But that isn’t the only potential shock. Other changes coming soon — stemming from proposals by the administration of President Donald Trump — could affect […]

Health CareBecause of past fraud by rogue brokers, some Affordable Care Act policyholders may get an unexpected tax bill this season.

But that isn’t the only potential shock. Other changes coming soon — stemming from proposals by the administration of President Donald Trump — could affect their coverage and its cost. And sorting out related problems and challenges may take longer as federal workers are laid off and funding for assistance programs is cut.

First up: Taxes

Tax season is when some consumers learn they were fraudulently enrolled in an ACA plan or switched to a different one without their knowledge.

Those unauthorized enrollments or changes took off in late 2023 and continued through last year, drawing more than 274,000 complaints in the first eight months of 2024 to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, mostly about rogue agents or call centers.

Tax problems can arise if those enrollments resulted in premium tax credits exceeding the amount the consumer should have received. In those cases, consumers may have to pay all or part of those credits back. The amount owed could range from a few hundred dollars to thousands, with some caps based on income.

The first clue some people have is when they get a 1095-A form in the mail.

Those documents are sent out by the state and federal marketplaces to the IRS and ACA enrollees, showing any tax credit payments made to health insurers on a taxpayer’s behalf. Taxpayers use the premium tax credit information from the 1095-A when completing their return.

Returns can be held up if the IRS has information indicating the taxpayer has ACA coverage that they failed to report on their return, or if there are other discrepancies.

The Biden administration last year took steps to slow the fraudulent switching, including requiring a three-way call between the broker, client, and marketplace for some enrollment issues.

“While we may be seeing less [fraud], we’re still dealing with 2024 taxes,” said Erin Kinard, director of systems and intake for the Health and Economic Opportunity Program at Pisgah Legal Services, a nonprofit serving western North Carolina that offers both legal help and assistance with ACA problems.

Consumers who suspect they were fraudulently enrolled should immediately call their federal or state ACA marketplace, experts say. Some consumers will be referred to special federal caseworkers through the marketplaces. But some of those caseworkers are now part of the broad reduction in force by the Trump administration.

In recent days, “they laid off two divisions on the Affordable Care Act side,” said Jeffrey Grant, who oversaw ACA issues as CMS’ deputy director for operations in the Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight before leaving in February.

With fewer caseworkers, “it will take longer to get problems taken care of,” said Grant, who is now president of Schedule F Healthcare Strategies, a consulting group that aims to help laid-off federal workers find new jobs. “The marketplace is twice as big as it was the last time the Trump administration was here, and now they are cutting caseworkers to less than were around then.”

And these cases are difficult because the rogue brokers who enrolled consumers sometimes misstated their income so they would qualify for the largest tax credits possible. Other consumers have found they were enrolled even though they had affordable employer coverage, making them ineligible for ACA subsidies.

That’s what happened to Anthony Akra and his wife, Ashley Zukoski, in Charlotte, North Carolina. They were enrolled in a plan without their knowledge in 2023, by a broker in Florida with whom they had never spoken. The couple had health insurance through Zukoski’s employer. The broker listed an income that qualified the household for a large subsidy that fully offset the monthly premium cost, so the couple never received a bill. One day, a 1095-A form showed up in their mailbox.

“I didn’t know what the hell it was,” said Akra, who said the form showed that he had been receiving hundreds of dollars a month in premium tax credits. He would owe a big chunk of that back unless he could get the plan retroactively canceled.

Because their pharmacy, part of a national chain, had switched them to the new plan, also without telling them, they had used the new coverage every time they filled a prescription. That inadvertent use of the policy complicated their efforts to get the fraudulent coverage revoked. Meanwhile, the IRS withheld more than $4,000 from their tax refund based on the information sent through that 1095-A form. Months passed, but with assistance from a “navigator” program — a government-funded nonprofit that helps people deal with insurance problems — they were able to get the incorrect insurance canceled and a refund at the end of October.

It is not unusual for people to spend weeks or even months trying to sort out the mess, said Kinard, whose organization is similar to the one that helped Akra.

While navigator programs nationwide are still operating to help people sign up for health coverage or address issues, the Trump administration has targeted their funding for a 90% cut.

Meanwhile, ACA enrollees may face a range of other surprises due to policy and budget steps proposed by the Trump administration.

More Potential Changes

Congress must decide whether to extend premium tax credits that were enhanced during the covid pandemic, which expanded eligibility for the credits and made them larger for many enrollees. Keeping them in place would be expensive, with the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office and Joint Committee on Taxation estimating it would add $335 billion to the deficit through 2034.

That debate will come amid another deficit-affecting decision: whether to extend tax cuts enacted during the first Trump administration, which would add trillions to the budget deficit through 2034.

If the enhanced subsidies are not renewed, monthly premium costs would rise by an average of over 75%, according to KFF, a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News. Premiums could more than double in some states, including many GOP-led ones, such as Texas, Mississippi, Utah, Wyoming, and West Virginia.

That could spark a political backlash. Additionally, the enhanced subsidies are seen as a main reason for strong enrollment growth, leading to more than 24 million people signing up for ACA plans for this year. A recent KFF study found the 15 states with the most enrollment growth since 2020 were all won by Trump in 2024.

A proposed rule released last month by the Trump administration includes provisions to shorten the annual enrollment period, get rid of a special open enrollment period that allows low-income people to sign up year-round, and require stricter verification of income and other information when people apply for coverage. The administration says most of these steps are needed to reduce fraud in the system.

The administration estimates that 750,000 to 2 million fewer people would enroll in coverage as a result of the changes.

The new rule, if finalized, will make it harder for people to enroll, said Xonjenese Jacobs, director of Florida Covering Kids & Families at the University of South Florida College of Public Health. Losing the year-round enrollment for very low-income people, for example, would affect people short on cash who move often to stay with relatives or friends, and those who have unsteady employment, making it hard to know when or where to enroll and what their income might be in the coming year.

“They don’t have the same ability to plan,” Jacobs said. “It’s definitely going to make a difference for a lot of the individuals that we service.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Ontario schools start suspending students with incomplete immunization

Toronto Public Health says about 10,000 students are not-up-to-date on their vaccinations, and a first group of 173 students in Grade 11 will be suspended Tuesday.

MeaslesToronto Public Health says about 10,000 students are not-up-to-date on their vaccinations, and a first group of 173 students in Grade 11 will be suspended Tuesday.

This Bill Aims To Help Firefighters With Cancer. Getting It Passed Is Just the Beginning.

As firefighters battled the catastrophic blazes in Los Angeles County in January, California’s U.S. senators, Adam Schiff and Alex Padilla, signed onto legislation with a simple aim: Provide federal assistance to first responders diagnosed with service-related cancer. The Honoring Our Fallen Heroes Act is considered […]

Rural HealthAs firefighters battled the catastrophic blazes in Los Angeles County in January, California’s U.S. senators, Adam Schiff and Alex Padilla, signed onto legislation with a simple aim: Provide federal assistance to first responders diagnosed with service-related cancer.

The Honoring Our Fallen Heroes Act is considered crucial by its supporters, with climate change fueling an increase in wildfire frequency and firefighting deemed carcinogenic by the World Health Organization. Firefighters have a 14% higher chance of dying from cancer than the general population, according to a 2024 study, and the disease was responsible for 66% of career firefighter line-of-duty deaths from 2002 to 2019.

The Los Angeles wildfires brought the fear generated by these statistics into bold relief. As homes, businesses, and cars — and the products within them — were incinerated, gases, chemicals, asbestos, and other toxic pollutants were released into the air, often settling into soil and dust. First responders working at close range, often without adequate respiratory protection, were at higher risk of developing adverse health conditions.

Just days after the fires were contained, researchers tested a group of 20 firefighters who had come from Northern California to help battle the flames and found dangerously elevated levels of lead and mercury in their blood.

“Firefighters and first responders put their lives on the line without a second thought to protect California communities from the devastating Southern California fires,” Padilla said in a statement. “When they sacrifice their lives or face severe disabilities due to service-related cancers, we have a shared duty to help get their families back on their feet.”

But while the Honoring Our Fallen Heroes Act has bipartisan support, it still faces a rough road politically, and those who’ve spent years dealing with similar government-run programs warn of major implementation issues should the measure become law.

The Senate Judiciary Committee passed a similar bill in 2024, but the measure didn’t advance to a vote on the floor. And with legislators pondering potentially massive federal budget cuts, its fate in Congress this year is far from clear. What is clear is that, for legislation tying benefits to service-related health conditions, the devil is in the details.

“Getting the piece of legislation passed is not as hard as guarding it,” said John Feal, who was injured at the 9/11 ground zero site while working as a demolition supervisor. He has since become a fierce advocate for first responders and military veterans.

“You will watch the legislation mature, as more and more people who need the assistance come forward,” Feal said. At that point, he added, the program’s capacity to grow — and to successfully process the applications of those who’ve come forward for help — may become a challenge.

That, Feal said, is what happened with the various government programs created after the 9/11 attacks to provide monetary compensation and health care to injured first responders, including some later diagnosed with cancer. Both the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund and the World Trade Center Health Program encountered substantial funding issues and were beset by logistical failures.

The structure of the Honoring Our Fallen Heroes Act, sponsored by Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), might allow it to sidestep some funding pitfalls. Rather than create a new benefit program, the bill would grant firefighters who have non-9/11 cancer-related conditions access to the long-standing Public Safety Officers’ Benefits Program, which provides monetary death, disability, and education benefits to line-of-duty responders and surviving family members.

Death benefits in such programs are considered mandatory spending and are funded regardless of congressional budget decisions. Funding for disability and education benefits, however, depends on annual appropriations.

Even with full funding, the legislation could face implementation problems similar to those plaguing the 9/11 programs, including complex eligibility criteria, difficulty documenting that illnesses are service-related, and — more recently — long waits to enroll amid seesawing federal attempts at cutbacks.

Attorney Michael Barasch represented the late New York police detective James Zadroga, who developed pulmonary fibrosis from toxic exposure at the World Trade Center site and for whom the 9/11 Health and Compensation Act is named. Barasch, who still represents 9/11 victims and lobbies Congress for program improvements and funding, said the Honoring Our Fallen Heroes Act should streamline the process for first responders to document that their cancers are related to fighting wildfires.

“In my experience representing more than 40,000 members of the 9/11 community, any similar program should have a clear set of standards to determine eligibility,” Barasch told KFF Health News. “Needless complexity creates a serious risk that responders who should have been eligible might not have access to benefits.”

Feal added that lawmakers should be ready to bolster funding to adequately staff the Public Safety Officers’ Benefits Program if it adds to the conditions currently covered, noting that the 9/11 programs have swelled as more and more first responders have presented service-related conditions.

“There were 75,000 people in the program in 2015. There’s now close to 140,000,” Feal said. “There’s a backlog on enrollment into the WTC program because they’re understaffed, and there’s also a backlog on getting your illnesses certified so you can get compensated.”

As the Public Safety Officers’ Benefits Program is currently implemented, firefighters and other first responders are eligible for support for physical injuries they incur in the line of duty or for deaths from duty-related heart attacks, strokes, mental health conditions, and 9/11-related illnesses. The bill would add provisions for those who die or become permanently disabled from other service-related cancers.

A study has already been launched to track the short- and long-term health impacts of the Los Angeles wildfires. “This was an environmental and health disaster that will unfold over decades,” Kari Nadeau, a professor at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said in announcing the study.

Firefighters who battled the massive 2018 Camp Fire in Northern California, meanwhile, have been found to carry higher levels of carcinogens and other toxic substances in their blood than the general population, according to a study commissioned by the San Francisco Firefighters Cancer Prevention Foundation.

The Honoring Our Fallen Heroes Act was first introduced in 2023 and reintroduced on Jan. 23 of this year, with Klobuchar referencing the California wildfires in her press release. The Congressional Budget Office estimated last year that the bill would cost about $250 million annually from 2024 to 2034; it has not weighed in since the measure was reintroduced.

“Cancer’s grip on the fire service is undeniable,” said Edward Kelly, president of the International Association of Fire Fighters. “When a firefighter dies from occupational cancer, we owe it to them to ensure their families get the line-of-duty death benefits they are owed.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Rural Hospitals and Patients Are Disconnected From Modern Care

If you regularly experience connection issues, click here to read a version of this story designed to open faster in low-signal areas. EUTAW, Ala. — Leroy Walker arrived at the county hospital short of breath. Walker, 65 and with chronic high blood pressure, was brought […]

Rural HealthIf you regularly experience connection issues, click here to read a version of this story designed to open faster in low-signal areas.

EUTAW, Ala. — Leroy Walker arrived at the county hospital short of breath. Walker, 65 and with chronic high blood pressure, was brought in by one of rural Greene County’s two working ambulances.

Nurses checked his heart activity with a portable electrocardiogram machine, took X-rays, and tucked him into Room 122 with an IV pump pushing magnesium into his arm.

“I feel better,” Walker said. Then: Beep. Beep. Beep.

The Greene County Health System, with only three doctors, has no intensive care unit or surgical services. The 20-bed hospital averages a few patients each night, many of them, like Walker, with chronic illnesses.

Greene County residents are some of the sickest in the nation, ranking near the top for rates of stroke, obesity, and high blood pressure, according to data from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Patients entering the hospital waiting area encounter floor tiles that are chipped and stained from years of use. A circular reception desk is abandoned, littered with flyers and advertisements.

But a less visible, more critical inequity is working against high-quality care for Walker and other patients: The hospital’s internet connection is a fraction of what experts say is sufficient. High-speed broadband is the new backbone of America’s health care system, which depends on electronic health records, high-tech wireless equipment, and telehealth access.

Greene is one of more than 200 counties with some of the nation’s worst access to not only reliable internet, but also primary care providers and behavioral health specialists, according to a KFF Health News analysis. Despite repeated federal promises to support telehealth, these places remain disconnected.

During his first term, President Donald Trump signed an executive order promising to improve “the financial economics of rural healthcare” and touted “access to high-quality care” through telehealth. In 2021, President Joe Biden committed billions to broadband expansion.

KFF Health News found that counties without fast, reliable internet and with shortages of health care providers are mostly rural. Nearly 60% of them have no hospital, and hospitals closed in nine of the counties in the past two decades, according to data collected by the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

Residents in these “dead zone” counties tend to live sicker and die younger than people in the rest of the United States, according to KFF Health News’ analysis. They are places where systemic poverty and historical underinvestment are commonplace, including the remote West, Appalachia, and the rural South.

“It will always be rural areas with low population density and high poverty that are going to get attended to last,” said Stephen Katsinas, director of the Education Policy Center at the University of Alabama. “It’s vital that the money we do spend be well deployed with a thoughtful plan.”

Now, after years of federal and state planning, Biden’s $42 billion Broadband Equity Access and Deployment, or BEAD, program, which was approved with bipartisan support in 2021, is being held up, just as states — such as Delaware — were prepared to begin construction. Trump’s new Department of Commerce secretary, Howard Lutnick, has demanded “a rigorous review” of the program and called for the elimination of regulations.

Trump’s nominee to lead the federal agency overseeing the broadband program, Arielle Roth, repeatedly said during her nomination hearing in late March that she would work to get all Americans broadband “expeditiously.” But when pressed by senators, Roth declined to provide a timeline for the broadband program or confirm that states would receive promised money.

Instead, Roth said, “I look forward to reviewing those allocations and ensuring the program is compliant with the law.”

Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.), the Senate commerce committee’s ranking minority member, said she wished Roth had been more committed to delivering money the program promised.

The political wrangling in Washington is unfolding hundreds of miles from Greene County, where only about half of homes have high-speed internet and 36% of the population lives below the poverty line, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Walker has lived his life in Alabama’s Black Belt and once worked as a truck driver. He said his high blood pressure emerged when he was younger, but he didn’t take the medicine doctors prescribed. About 11 years ago, his kidneys failed. He now needs dialysis three times a week, he said.

While lying in the hospital bed, Walker talked about his dialysis session the day before, on his birthday. As he talked, the white sheet covering his arm slipped and revealed where the skin around his dialysis port had swollen to the size of a small grapefruit.

Room 122, where Walker rested, is sparse with a single hospital bed, a chair, and a TV mounted on the wall. He was connected to the IV pump, but no other tubes or wires were attached to him. The IV machine’s beeping echoed through the hallway outside. Staffers say they must listen for the high-pitched chirps because the internet connection at the hospital is too slow to support a modern monitoring system that would display alerts on computers at the nurses’ station.

Aaron Brooks, the hospital’s technology consultant, said financial challenges keep Greene County from buying monitoring equipment. The hospital reported a $2 million loss on patient care in its most recent federal filing. Even if Greene could afford a system, it does not have the thousands of dollars to install a high-speed fiber-optic internet connection necessary to operate it, he said.

Lacking central monitoring, registered nurse Teresa Kendrick carries a portable pulse oximeter device, she said — like ones sold at drugstores that surged in popularity during the covid-19 pandemic.

Doing her job means a “continuous spot-check,” Kendrick said. Another longtime nurse described her job as “a lot of watching and checking.”

Beep. Beep.

The beeping in Room 122 persisted for more than two minutes as Walker talked. He wasn’t in pain — he was just worried about the beeping.

About 50 paces down the hall — past the pharmacy, an office, and another patient room — registered nurse Jittaun Williams sat at her station behind plexiglass. She was nearly 20 minutes past the end of her 12-hour shift and handing off to the three night-shift nurses.

They discussed plans for patients’ care, reviewing electronic records and flipping through paper charts. The nurses said the hospital’s internal and external computer systems are slow. They handwrite notes on paper charts in a patient’s room and duplicate records electronically. “Our system isn’t strong enough. There are many days you kind of sit here and wait,” Williams said.

Broadband dead zones like Greene County persist despite decades of efforts by federal lawmakers that have created a patchwork of more than 133 funding programs across 15 agencies, according to a 2023 federal report.

Alabama’s leaders, like others around the U.S., are actively spending federal funds from the Biden-era American Rescue Plan Act, according to public records. And Greene County Hospital is on the list of places waiting for ARPA construction, according to agreements provided by the Alabama Department of Economic and Community Affairs.

“It is taking too long, but I am patient,” said Alabama state Sen. Bobby Singleton, a Democrat who represents the district that includes Greene County Hospital and two others he said lack fast-enough connectivity. Speed bumps such as a need to meet federal requirements and a “big fight” to get internet service providers to come into his rural district slowed the release of funds, Singleton said.

Alabama received its first portion of ARPA funds in June 2021, which Singleton said included money for building fiber-optic cables to anchor institutions like the hospital. Alabama’s awards require the projects to be completed by February 2026 — nearly five years after money initially flowed to the state.

Singleton said he now sees fiber lines being built in his district every day and knows the hospital is “on the map” to be connected. “This doesn’t just happen overnight,” he said.

Alabama Fiber Network, a consortium of electric cooperatives, won a total of $45.7 million in ARPA funding specifically for construction to anchor institutions in Greene and surrounding counties. James Hoffman, vice president of external affairs for AFN, said the company is ahead of schedule. It plans to offer the hospital a monthly service plan that uses fiber-optic lines by year’s end, he said.

Greene County Health System chief executive Marcia Pugh confirmed that she had talked with multiple companies but said she wasn’t sure the work would be complete in the time frame the companies predicted.

“You know, you want to believe,” Pugh said.

Beep. Beep.

Nurse Williams had finished the night-shift handoff when she heard beeps from Walker’s room.

She rushed toward the sound, accidentally ducking into Room 121 before realizing her mistake.

Once in Walker’s room, Williams pressed buttons on the IV pump. The magnesium flowing in the tube had stopped.

“You had a little bit more left in the bag, so I just turned it back on,” Williams told Walker. She smiled gently and asked if he was warm enough. Then she hand-checked his heart rate and adjusted his sheets. At the bottom of the bed, Walker’s feet hung off the mattress and Williams gently moved them and made sure they were covered.

Walker beamed. At this hospital, he said, “they care.”

As rural hospitals like Greene’s wait for fast-enough internet, nurses like Williams are “heroes every single day,” said Aaron Miri, an executive vice president and the chief digital and information officer for Baptist Health in Jacksonville, Florida.

Miri, who served under both Democratic and Republican administrations on Department of Health and Human Services technology advisory committees, said hospitals need at least a gigabit of speed — which is 1,000 megabits per second — to support electronic health records, video consultations, the transfer of scans and images, and continuous remote monitoring of patients’ heartbeats and other vital signs.

But Greene’s is less than 10% of that level, recorded on the nurses’ station computer as nearly 90 megabits per second for upload and download speeds.

It’s a “heartbreaking” situation, Miri said, “but that’s the reality of rural America.”

The Beeping Stopped

Michael Gordon, one of the hospital’s three doctors, arrived the next morning for his 24-hour shift. He paused in Room 122. Walker had been released overnight.

Not being able to monitor a cardiovascular patient’s heart rhythm, well, “that’s a problem,” Gordon said. “You want to know, ‘Did something really change or is that just a crazy IV machine just beeping loud and proud and nobody can hear it?’”

Despite the lack of modern technology tools, staffers do what they can to take care of patients, Pugh said. “We show the community that we care,” she said.

Pugh, who started her career as a registered nurse, arrived at the hospital in 2017. It was “a mess,” she said. The hospital was dinged four years in a row, starting in 2016, with reduced Medicare payments for readmitting patients. Pugh said that at times the hospital had not made payroll. Staff morale was low.

In 2021, federal inspectors notified Pugh of an “immediate jeopardy” violation — grounds for regulators to shut off federal payments — because of an Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act complaint. Among seven deficiencies inspectors cited, the hospital failed to provide a medical screening exam or stabilizing treatment and did not arrange appropriate transfer for a 23-year-old woman who arrived at the hospital in labor, according to federal reports.

Inspectors also said the hospital failed to ensure a doctor was on duty and failed to create and maintain medical records. An ambulance took the woman to another hospital, where the baby was “pronounced dead upon arrival,” according to the report.

Federal inspectors required the hospital to take corrective actions and a follow-up inspection in July 2021 found the hospital to be in compliance.

In 2023, federal inspectors again cited the hospital’s failure to maintain records and noted it had the “potential to negatively affect patients.”

Inspectors that year found that medical records for four discharged patients had been lost. The “physical record” included consent forms, physician orders, and treatment plans and was found in another department, where it had been left for two months.

Pugh declined to comment on the immediate jeopardy case. She confirmed that a lack of internet connectivity and use of paper charts played a role in federal findings, though she emphasized the charts were discharge papers rather than for patients being treated.

She said she understands why federal regulators require electronic health records but “our hospitals just aren’t the same.” Larger facilities that can “get the latest and greatest” compared with “our facilities that just don’t have the manpower or the financials to purchase it,” she said, “it’s two different things.”

Walker, like many rural Americans, relies on Medicaid, a joint state and federal insurance program for people with low incomes and disabilities. Rural hospitals in states such as Alabama that have not expanded Medicaid coverage to a wider pool of residents fare worse financially, research shows.

During Walker’s stay, because the hospital can’t afford to modernize its systems, nurses dealt with what Pugh later called an “astronomical” number of paper forms.

Later, at Home

Walker sat on the couch in the modest brick home he shares with his sister and nephew. In a pinch, Greene County Hospital, he said, is good “for us around here. You see what I’m saying?”

Still, Walker said, he often bypasses the county hospital and drives up the road to Tuscaloosa or Birmingham, where they have kidney specialists.

“We need better,” Walker said, speaking for the 7,600 county residents. He wondered aloud what might happen if he didn’t make it to the city for specialty care.

Sometimes, Walker said, he feels “thrown away.”

“People done forgotten about me, it feels like,” he said. “They don’t want to fool with no mess like me.”

Maybe Greene County’s health care and internet will get better, Walker said, adding, “I hope so, for our sake out in a rural area.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Alberta measles outbreak not dire enough to warrant CMOH public address: LaGrange

The new cases come as the Edmonton Zone Medical Staff Association blamed the spread on inaction, calling for a government-initiated vaccination plan and better public updates.

MeaslesThe new cases come as the Edmonton Zone Medical Staff Association blamed the spread on inaction, calling for a government-initiated vaccination plan and better public updates.

43 cases of measles in Alberta, outbreak east of Edmonton prompts public alert

The number of confirmed cases of measles keeps growing across Alberta and an outbreak has been identified in Two Hills, prompting a public health alert.

MeaslesThe number of confirmed cases of measles keeps growing across Alberta and an outbreak has been identified in Two Hills, prompting a public health alert.