Trump Team’s $500 Million Bet on Old Vaccine Technology Puzzles Scientists

The Trump administration’s unprecedented $500 million grant for a broadly protective flu shot has confounded vaccine and pandemic preparedness experts, who said the project was in early stages, relied on old technology, and was just one of more than 200 such efforts. Health and Human […]

Pharmaceuticals

An Arm and a Leg: Why ‘The Pitt’ Is Our Fave New Drama

People who work in real-life emergency rooms have raved about how the new TV drama “The Pitt” accurately captures the complex dynamics of their workplaces and the medical details of their cases. Host Dan Weissmann talks with Alex Janke, an emergency medicine doctor and health […]

Health Care

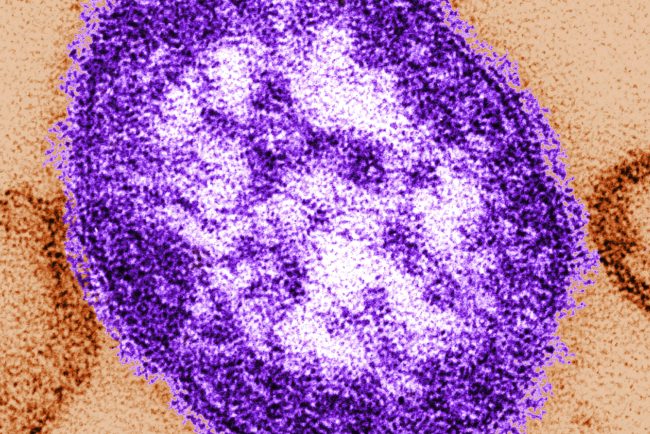

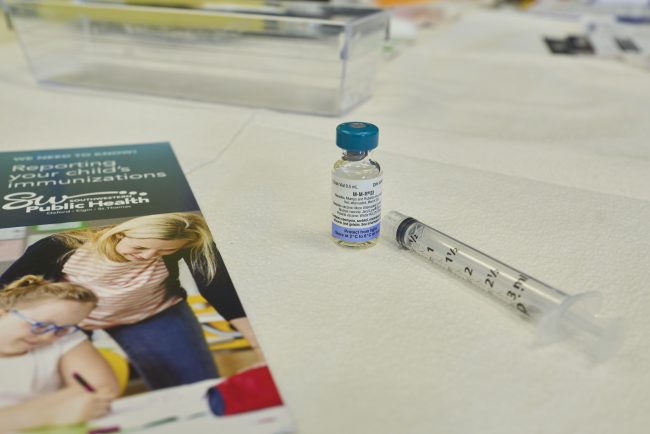

Measles exposure alert issued for communities south of Winnipeg

Public health officials in Manitoba are warning of new measles exposure sites in two communities south of Winnipeg, including a medical centre and an elementary school.

Measles

Education minister ‘concerned’ by vaccination rates amidst Ontario measles outbreak

The province has been dealing with a measles outbreak since the end of last year, with hundreds of new cases reported weekly. Some schools have suspended students.

MeaslesThe province has been dealing with a measles outbreak since the end of last year, with hundreds of new cases reported weekly. Some schools have suspended students.

Alberta’s top public health doctor reminding public to get their measles vaccine

Alberta’s Chief Medical Officer of Health said the number of confirmed cases of measels in the province doesn’t reflect the number of people who may have been exposed to the virus.

MeaslesAlberta’s Chief Medical Officer of Health said the number of confirmed cases of measels in the province doesn’t reflect the number of people who may have been exposed to the virus.

Families of Transgender Youth No Longer View Colorado as a Haven for Gender-Affirming Care

In recent years, states across the Mountain West have passed laws that limit doctors from providing transgender children with certain kinds of gender-affirming care, from prohibitions on surgery to bans on puberty blockers and hormones. Colorado families say their state was a haven for those […]

Rural HealthIn recent years, states across the Mountain West have passed laws that limit doctors from providing transgender children with certain kinds of gender-affirming care, from prohibitions on surgery to bans on puberty blockers and hormones. Colorado families say their state was a haven for those health services for a long time, but following executive orders from the Trump administration, even hospitals in Colorado limited the care they offer for trans patients under age 19. KFF Health News Colorado correspondent Rae Ellen Bichell spoke with youth and their families.

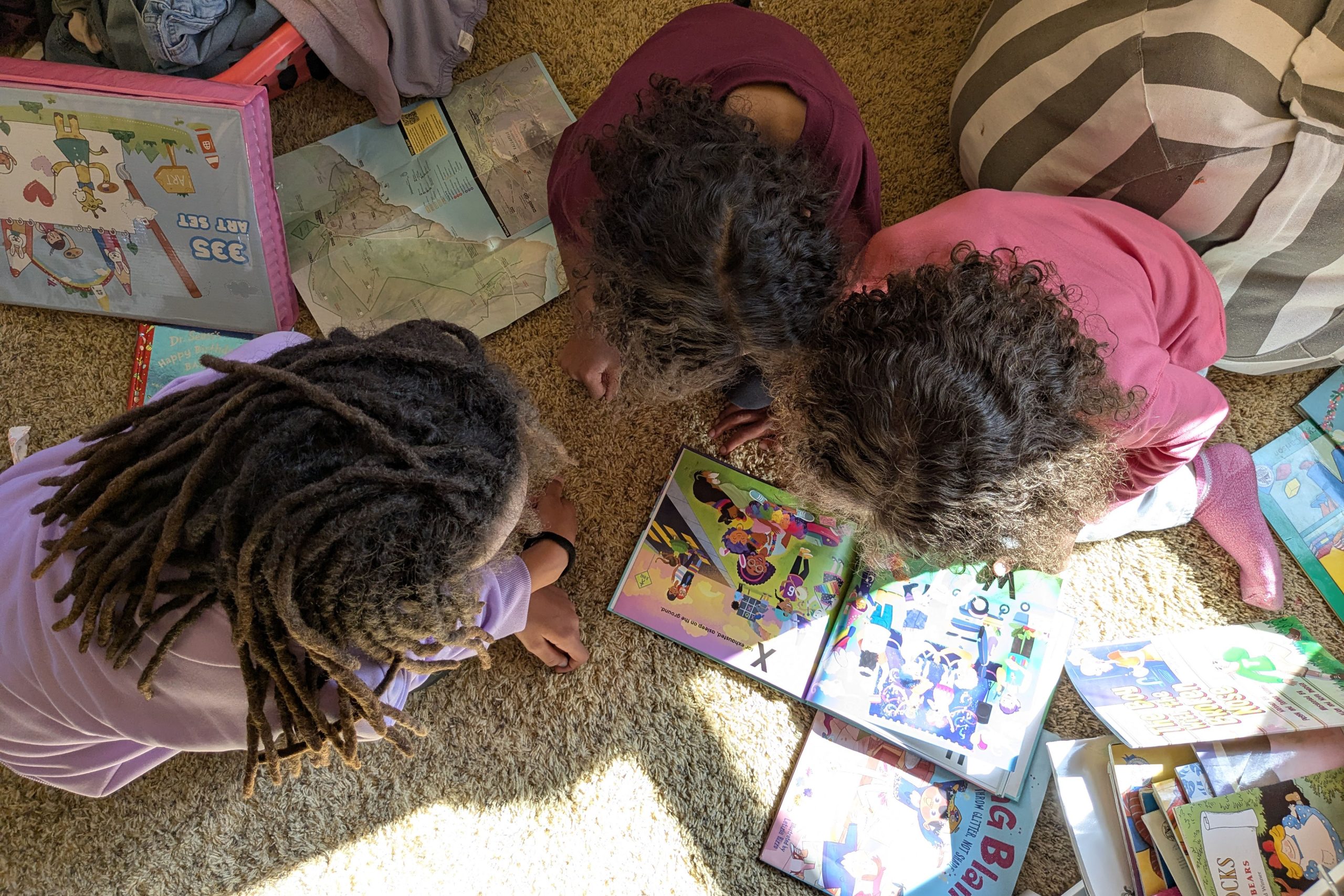

GRAND JUNCTION, Colo. — On a Friday after school, 6-year-old Esa Rodrigues had unraveled a ball of yarn, spooked the pet cat, polled family members about their favorite colors, and tattled on a sibling for calling her a “butt-face mole rat.”

Next, she was laser-focused on prying open cherry-crisp-flavored lip gloss with her teeth.

“Yes!” she cried, twisting open the cap. Esa applied the gloopy, shimmery stuff in her bedroom, where a large transgender pride flag hung on the wall.

Esa said the flag makes her feel “important” and “happy.” She’d like to take it down from the wall and wear it as a cape.

Her parents questioned her identity at first, but not anymore. Before, their anxious child dreaded going to school, bawled at the barbershop when she got a boy’s haircut, and curled into a fetal position on the bathroom floor when she learned she would never get a period.

Now, that child is happily bounding up a hill, humming to herself, wondering aloud if fairies live in the little ceramic house she found perched on a stone.

Her mom, Brittni Packard Rodrigues, wants this joy and acceptance to stay. Depending on a combination of Esa’s desire, her doctors’ recommendations, and when puberty sets in, that might require puberty blockers, followed by estrogen, so that Esa can grow into the body that matches her being.

“In the long run, blockers help prevent all of those surgeries and procedures that could potentially become her reality if we don’t get that care,” Packard Rodrigues said.

The medications known as puberty blockers are widely used for conditions that include prostate cancer, endometriosis, infertility, and puberty that sets in too early. Now, the Trump administration is seeking to limit their use specifically for transgender youth.

Esa’s home state of Colorado has long been known as a haven for gender-affirming care, which the state considers legally protected and an essential health insurance benefit. Medical exiles have moved to Colorado for such treatment in the past few years. As early as the 1970s, the town of Trinidad became known as “the sex-change capital of the world” when a cowboy-hat-wearing former Army surgeon, Stanley Biber, made his mark performing gender-affirming surgeries for adults.

On his first day in office, President Donald Trump signed an executive order refuting the existence of transgender people by saying it is a “false claim that males can identify as and thus become women and vice versa.” The following week, he issued another order calling puberty blockers and hormones for anyone under age 19 a form of chemical “mutilation” and “a stain on our Nation’s history.” It directed agencies to take steps to ensure that recipients of federal research or education grants stop providing it.

Subsequently, health care organizations in Colorado; California; Washington, D.C.; and elsewhere announced they would preemptively comply. In Colorado, that included three major health care organizations: Children’s Hospital Colorado, Denver Health, and UCHealth. At the end of January and in early February, the three systems announced changes to the gender-affirming care they provide to patients under 19, effective immediately: no new hormone or puberty blocker prescriptions for patients who hadn’t had them before, limited or no prescription renewals for those who had, and no surgeries, though Children’s Hospital had never offered it, and such surgery is rare among teens: For every 100,000 trans minors, fewer than three undergo surgery.

Children’s Hospital and Denver Health resumed offering puberty blockers and hormones on Feb. 24 and Feb. 19, respectively, after Colorado joined a U.S. District Court lawsuit in Washington state. The court concluded that Trump’s orders relating to gender “discriminate on the basis of transgender status and sex.” It granted a preliminary injunction blocking them from taking effect in the four states involved in the lawsuit.

Surgeries, however, have not resumed. Denver Health said it will “continue its pause on gender-affirming surgeries for patients under 19 due to patient safety and given the uncertainty of the legal and regulatory landscape.”

UCHealth has resumed neither medication nor surgery for those under 19. “Our providers are awaiting a more permanent decision from federal courts that may resolve the uncertainty around providing this care,” spokesperson Kelli Christensen wrote.

Trans youth and their families said the court ruling and the two Colorado health systems’ decisions to resume treatments haven’t resolved matters. It has bought them time to stockpile prescriptions, to try to find private practice physicians with the right training to monitor blood work and adjust prescriptions accordingly, and, for some, to work out the logistics of moving to another state or country.

The Trump administration has continued to press health providers beyond the initial executive orders by threatening to withhold or cancel federal money awarded to them. In early March, the Health Resources and Services Administration said it would review funding for graduate medical education at children’s hospitals.

KFF Health News requested comment from White House deputy press secretary Kush Desai but did not receive a response. HHS deputy press secretary Emily Hilliard responded with links to two prior press releases.

Medical interventions are just one type of gender-affirming care, and the process to get treatment is long and thorough. Researchers have found that, even among those with private insurance, transgender youth aren’t likely to receive puberty blockers and hormones. Interestingly, most gender-affirming breast reduction surgeries performed on men and boys are done on cisgender — not transgender — patients.

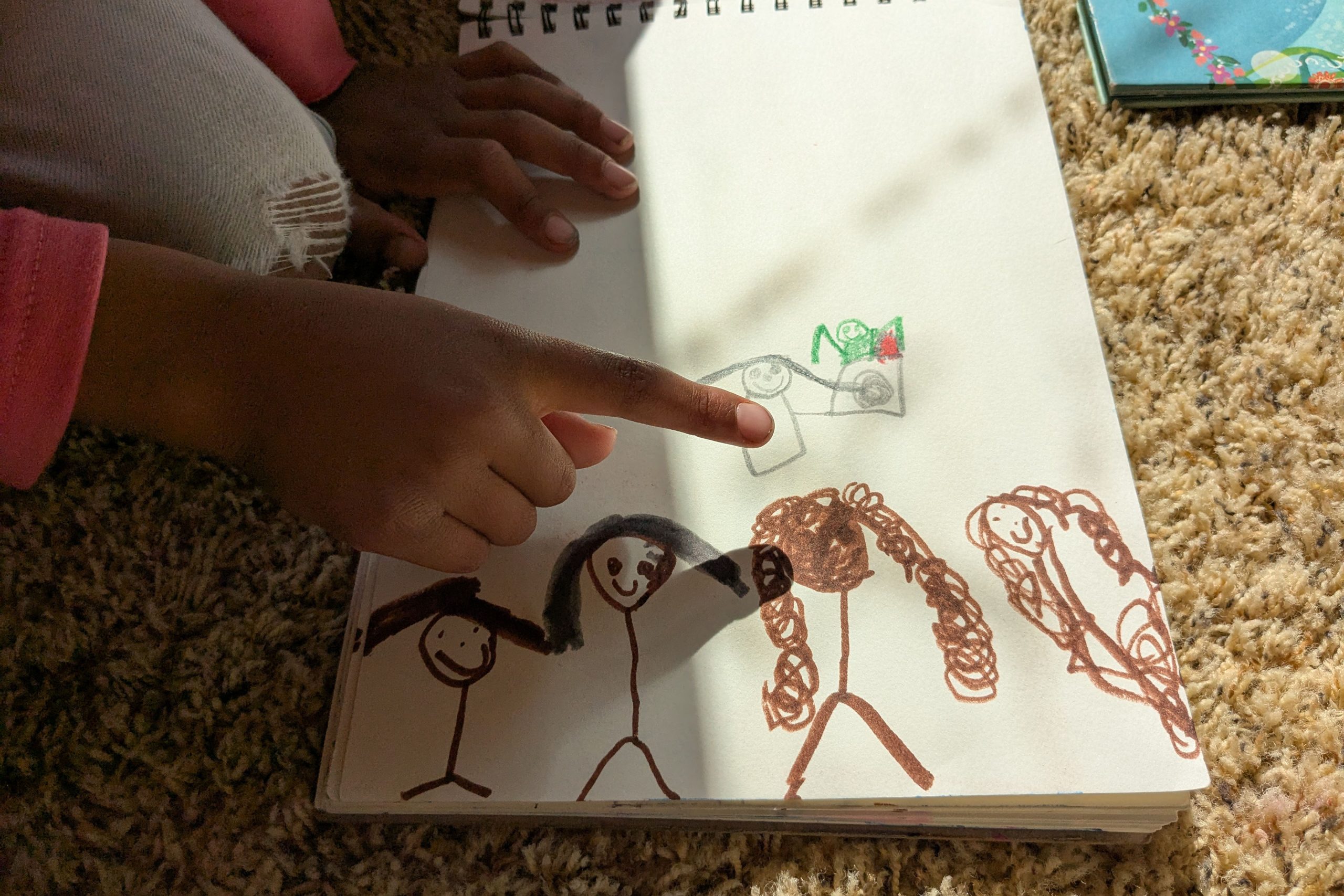

Kai, 14, wishes he could have gone on puberty blockers. He lives in Centennial, a Denver suburb. KFF Health News is not using his full name because his family is worried about him being harassed or targeted.

Kai got his period when he was 8 years old. By the time he realized he was transgender, in middle school, it was too late to start puberty blockers.

His doctors prescribed birth control to suppress his periods, so he wouldn’t be reminded each month of his gender dysphoria. Then, once he turned 14, he started taking testosterone.

Kai said if he didn’t have hormone therapy now, he would be a danger to himself.

“Being able to say that I’m happy in my body, and I get to be happy out in public without thinking everyone’s staring at me, looking at me weird, is such a huge difference,” he said.

His mom, Sherry, said she is happy to see Kai relax into the person he is.

Sherry, who asked to use her middle name to prevent her family from being identified, said she started stockpiling testosterone the moment Trump got elected but hadn’t thought about what impact there would be on the availability of birth control. Yet after the executive orders, that prescription, too, became tenuous. Sherry said Kai’s doctor at UCHealth had to set up a special meeting to confirm the doctor could keep prescribing it.

So, for now, Kai has what he needs. But to Sherry, that is cold comfort.

“I don’t think that we are very safe,” she said. “These are just extensions.”

The family is coming up with a plan to leave the country. If Sherry and her husband can get jobs in New Zealand, they’ll move there. Sherry said such mobility is a privilege that many others don’t have.

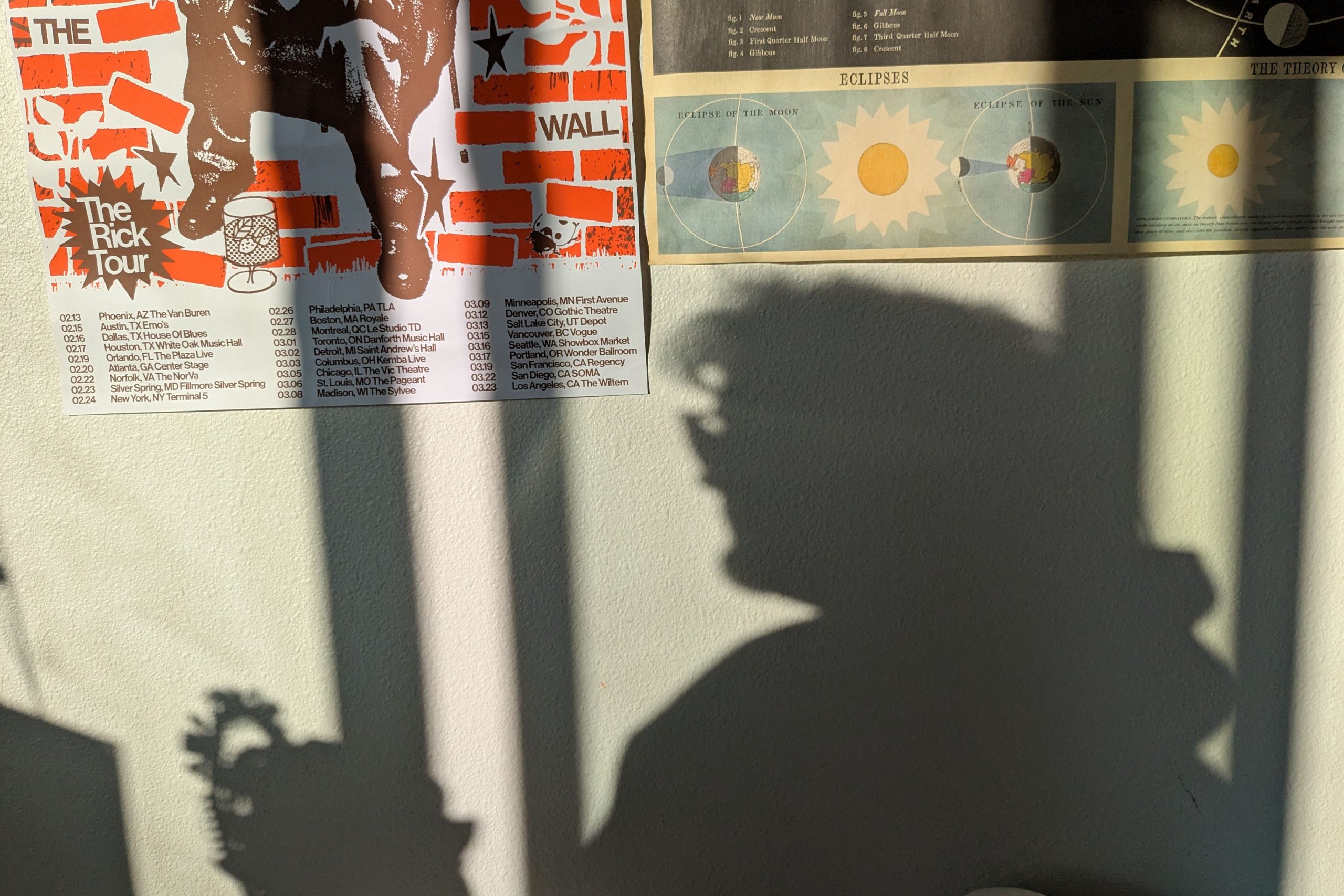

For example, David, an 18-year-old student at Western Colorado University in the Rocky Mountain town of Gunnison. He asked to be identified only by his middle name because he worries he could be targeted in this conservative, rural town.

David doesn’t have a passport, but even if he did, he doesn’t want to leave Gunnison, he said. He is studying geology, is learning to play the bass, and has a good group of friends. He has plans to become a paleontologist.

His dorm room shelves are scattered with his essentials: fossils, Old Spice deodorant, microwave macaroni and cheese. But there are no mirrors. David said he got in the habit of avoiding them.

“For the longest time, I just had so much body dysphoria and dysmorphia that it can be kind of hard to look in the mirror,” David said. “But when I do, most of the time, I see something that I really like.”

He’s been taking testosterone for three years, and the hormone helped him grow a beard. In January, his doctor at Denver Health was told to stop prescribing it. His mom drove hours from her home to Gunnison to deliver the news in person.

That prescription is back on track now, but the mastectomy he’d planned for this summer isn’t. He’d hoped to have adequate recovery time before sophomore year. But he doesn’t know anyone in Colorado who would perform it until he is 19. He could easily get surgery to enhance his breasts, but he must seek surgical options in other states to reduce or remove them.

“Colorado as a state was supposed to be a safe haven,” said his mother, Louise, who asked to be identified by her middle name. “We have a law that makes it a right for trans people to have health care, and yet our health care systems are taking that away.”

It has taken eight years and about 10 medical providers and therapists to get David this close to the finish line. That’s a big deal after living through so many years of dysphoria and dysmorphia.

“I’m still going, and I’m going to keep going, and there’s almost nothing they can do to stop me — because this is who I am,” David said. “There have always been trans people, and there always will be trans people.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

How stagnant vaccine funding caused measles to explode in Texas

The easily preventable disease, declared eliminated in the U.S. in 2000, ripped through communities sprawling across more than 20 Texas counties.

MeaslesThe easily preventable disease, declared eliminated in the U.S. in 2000, ripped through communities sprawling across more than 20 Texas counties.

Coca-Cola Coliseum concertgoers exposed to measles: Toronto Public Health

Toronto Public Health is warning people who attended a recent concert at Coca-Cola Coliseum that they may have been exposed to the measles.

MeaslesToronto Public Health is warning people who attended a recent concert at Coca-Cola Coliseum that they may have been exposed to the measles.

Journalists Delve Into Effects of Deep Federal Cuts on Public Health

KFF Health News chief Washington correspondent Julie Rovner and national public health correspondent Amy Maxmen discussed the impact of federal cuts on public health on Connecticut Public Radio’s “The Wheelhouse” on April 9. Click here to hear Rovner and Maxmen on “The Wheelhouse” Rovner also […]

Health CareKFF Health News chief Washington correspondent Julie Rovner and national public health correspondent Amy Maxmen discussed the impact of federal cuts on public health on Connecticut Public Radio’s “The Wheelhouse” on April 9.

Rovner also discussed the recent staff cuts and reorganization of the Department of Health and Human Services on WAMU’s “1A” on April 7 and on “Tradeoffs” on April 3. And she explored whether America is overmedicated — something Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has claimed — on “The Middle With Jeremy Hobson” on March 28.

- Click here to hear Rovner on “1A”

- Click here to hear Rovner on “Tradeoffs”

- Click here to hear Rovner on “The Middle With Jeremy Hobson”

KFF Health News Northern California correspondent Vanessa G. Sánchez discussed the impact of immigration policy on caregivers on Apple News’ “Apple News Today” on April 7.

- Click here to hear Sánchez on “Apple News Today”

- Read Sánchez and Daniel Chang’s “Immigration Crackdowns Disrupt the Caregiving Industry. Families Pay the Price.”

KFF Health News correspondent Daniel Chang discussed health care price transparency on KMOX’s “Total Information AM” on April 3.

- Click here to hear Chang on “Total Information AM”

- Read Chang’s “How Much Will That Surgery Cost? 🤷 Hospital Prices Remain Largely Unhelpful.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Measles vaccine lasts decades, experts say, pushing back on RFK Jr.

As United States Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. urges Americans to get the measles vaccine, he’s also casting doubt on it.

MeaslesAs United States Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. urges Americans to get the measles vaccine, he’s also casting doubt on it.

Some Rural Hospitals Ditch Medicare Advantage

Rural hospital leaders are questioning whether they can continue to afford to do business with Medicare Advantage companies, and some say the only way to maintain services and protect patients is to end their contracts with the private insurers. Medicare is the main federal health […]

Rural HealthRural hospital leaders are questioning whether they can continue to afford to do business with Medicare Advantage companies, and some say the only way to maintain services and protect patients is to end their contracts with the private insurers.

Medicare is the main federal health insurance program for people 65 or older. Participants can enroll in traditional, government-run Medicare or in a Medicare Advantage plan run by a private insurance company.

The private plans offer lower premiums and out-of-pocket costs for some patients. Nearly all offer extra benefits, such as vision, hearing, and dental coverage. Many also offer perks, such as gym memberships, nutrition services, and allowances for over-the-counter health supplies.

But in recent years, average Medicare Advantage reimbursements to rural hospitals were about 90% of what traditional Medicare paid, according to a new report from the American Hospital Association. And traditional Medicare already pays hospitals much less than private plans, according to a recent study by Rand Corp., a research nonprofit.

“The vast majority of our rural hospitals are not in a position where they can take further cuts to payment,” said Carrie Cochran-McClain, chief policy officer at the National Rural Health Association. “There are so many that are just really in a precarious financial spot.”

Nearly 200 rural hospitals have ended inpatient services or shuttered since 2005.

Jason Merkley, CEO of Brookings Health System in rural South Dakota, worried reimbursement losses would spark staff layoffs and cuts to patient services. So last year, the system dropped all four contracts it had with major Medicare Advantage companies.

Great Plains Health, which serves parts of rural Nebraska, Kansas, and Colorado, has dropped all contracts with the private insurers. So has Kimball Health Services, which is based in two small towns in Nebraska and Wyoming.

Rural hospital leaders are also concerned about Medicare Advantage payment delays and a resistance to authorizing patient care.

Susan Reilly, a spokesperson for the Better Medicare Alliance, said a recent report published by her group, which promotes Medicare Advantage, found that private plans are more affordable than traditional Medicare for rural beneficiaries. That analysis was conducted by an outside firm and based on a government survey.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Trump elimina la oficina que establece los niveles de pobreza vinculados a servicios para 80 millones de personas

Los despidos del presidente Donald Trump en el Departamento de Salud y Servicios Humanos (HHS) incluyeron a toda la oficina que establece las pautas federales de pobreza. Estas pautas determinan si decenas de millones de estadounidenses son elegibles para programas de salud como Medicaid, asistencia […]

Health CareLos despidos del presidente Donald Trump en el Departamento de Salud y Servicios Humanos (HHS) incluyeron a toda la oficina que establece las pautas federales de pobreza. Estas pautas determinan si decenas de millones de estadounidenses son elegibles para programas de salud como Medicaid, asistencia alimentaria, cuidado infantil y otros servicios, según dijo un ex funcionario.

El pequeño equipo, con experiencia en datos técnicos, trabajaba en la Oficina del Subsecretario de Planificación y Evaluación (ASPE) del HHS. Su despido se produjo de manera similar a otros: sin previo aviso y dejando a los funcionarios desconcertados sobre por qué fueron parte de la “RIF’ed”, como llaman a la “reducción de la fuerza de trabajo federal”, o sea, despedidos.

“Sospecho que hicieron una RIF en las oficinas que tenían la palabra ‘datos’ o ‘estadísticas’”, dijo uno de los empleados despedidos, un científico social a quien KFF Health News acordó no nombrar porque la persona teme nuevas represalias. “Por lo que sabemos, fue algo hecho al azar”.

Entre los despedidos estuvo Kendall Swenson, quien lideró el desarrollo de las directrices sobre pobreza durante muchos años y al que se considera un experto nacional sobre el tema, según el científico social y dos académicos que han trabajado en el equipo del HHS.

Los despidos y el cierre de la oficina podrían causar recortes en la asistencia a las familias de bajos ingresos el próximo año, a menos que la administración Trump restablezca los puestos o traslade sus funciones a otro lugar, expresó Robin Ghertner, director despedido de la División de Datos y Análisis Técnico, quien había supervisado las directrices sobre pobreza.

Estas directrices son “necesarias para muchas personas y programas”, dijo Timothy Smeeding, profesor emérito de economía en la Facultad de Asuntos Públicos La Follette, de la Universidad de Wisconsin. “Si piensas en alguien a quien despediste y que debería ser recontratado, Swenson sería un claro candidato”, añadió.

Según un proyecto de ley de asignaciones de 1981, el HHS debe tomar anualmente las cifras de la Oficina del Censo sobre el umbral de pobreza, ajustarlas a la inflación y crear directrices que las agencias y los estados utilicen para determinar quién tiene derecho a diversos tipos de ayuda.

Hay una estrategia especial para crear las directrices que incluye ajustes y cálculos, dijo Ghertner. Swenson y otros tres funcionarios prepararían los números de forma independiente y los comprobarían juntos antes de su publicación cada enero.

Según Ghertner, al personal de su oficina se les comunicó a principios de abril, sin previo aviso, que entraban en licencia administrativa hasta el 1 de junio, cuando su empleo terminaría oficialmente.

“No hay nadie en el gobierno que sepa cómo calcular estas directrices”, explicó. “Y como tenemos bloqueadas nuestras computadoras, no podemos enseñarle a nadie a calcularlas”.

El ASPE tenía unos 140 empleados y ahora tiene cerca de 40, según un ex funcionario. La reorganización del HHS fusionó la oficina con la Agencia para la Investigación y la Calidad del Cuidado de la Salud (AHRQ), cuyo personal se ha reducido de 275 a unos 80 empleados, según un ex funcionario de la AHRQ que habló bajo condición de anonimato.

El HHS ha dicho que se despidió a unos 10.000 empleados y ha comunicado que, junto con otras medidas, como un programa para fomentar las jubilaciones anticipadas, su plantilla se ha reducido en unos 20.000 trabajadores. Pero la agencia no ha detallado dónde ha hecho los recortes ni ha identificado a los empleados que ha despedido.

“A estos trabajadores se les dijo que no podían regresar a sus oficinas, por lo que no hay transferencia de conocimiento”, afirmó Wendell Primus, quien trabajó en la ASPE durante la administración de Bill Clinton. “No tuvieron tiempo de formar a nadie, transferir datos, etc”.

El HHS defendió los despidos. El departamento fusionó la AHRQ y la ASPE “como parte de la visión del secretario Kennedy de racionalizar el HHS para servir mejor a los estadounidenses”, dijo la vocera Emily Hilliard. “Los programas críticos dentro de la ASPE continuarán en esta nueva oficina” y “el HHS seguirá cumpliendo con los requisitos legales”, comunicó Hilliard en una respuesta escrita a KFF Health News.

Después de la publicación de este artículo, el vocero del HHS, Andrew Nixon, llamó a KFF Health News para decir que otros funcionarios del HHS podrían hacer el trabajo del equipo de análisis de datos de la RIF’ed, que tenía nueve miembros. “La idea de que esto se detendrá es totalmente incorrecta”, dijo. “Ochenta millones de personas no se verán afectadas”.

El secretario Robert F. Kennedy Jr. se ha negado hasta ahora a testificar sobre las reducciones de personal ante los comités del Congreso que supervisan gran parte de su agencia. El 9 de abril, una delegación de 10 legisladores demócratas esperó infructuosamente una reunión en el vestíbulo de la agencia.

A la cabeza del grupo estaba Diana DeGette (demócrata de Colorado) miembro de alto rango del subcomité de salud de la Cámara de Energía y Comercio, quien dijo a los periodistas que Kennedy debe comparecer ante el comité “y decirnos cuál es su plan para mantener a Estados Unidos sano y para detener estos recortes devastadores”.

Matt VanHyfte, vocero del comité republicano, afirmó que los funcionarios del HHS se reunirían con el personal bipartidista del comité el 11 de abril para discutir los despidos y otros asuntos de la política de la agencia.

El ASPE sirve como un grupo de expertos para el secretario del HHS, dijo Primus, quien más tarde fue asesor principal de política de salud de la legisladora Nancy Pelosi durante 18 años. Además de las directrices sobre pobreza, la oficina establece cuánto dinero de Medicaid va a cada estado y revisa todas las regulaciones desarrolladas por las agencias del HHS.

“Estos recortes de personal del HHS, de hasta 20,000 trabajadores, son una locura”, dijo Primus. “Estas decisiones no las han tomado Kennedy ni el personal del HHS. Se están tomando en la Casa Blanca. No hay ni pies ni cabeza en lo que están haciendo”.

Los líderes del HHS pueden desconocer su obligación legal de emitir las directrices de pobreza, según Ghertner. Y agregó que si cada estado y agencia gubernamental federal establece sus propias directrices, podría crear desigualdades y dar lugar a demandas.

Y mantener el estándar de 2025 el próximo año podría poner en riesgo los beneficios de cientos de miles de estadounidenses, advirtió Ghertner. El actual nivel de pobreza es de $15.650 para una persona soltera y de $32.150 para una familia de cuatro.

“Si ganas $30.000 y tienes tres hijos, por ejemplo, y el año que viene ganas $31.000, pero los precios han subido un 7%, de repente tus $31.000 no te compran lo mismo”, explicó, “pero si las directrices no han aumentado, es posible que ya no seas elegible para Medicaid”.

El nivel de pobreza de 2025 para una familia de cinco miembros es de $37.650.

En octubre, unas 79 millones de personas estaban inscritas en Medicaid o en el Programa de Seguro de Salud Infantil (CHIP), ambos sujetos a comprobación de recursos y, por lo tanto, dependientes de las pautas de pobreza para determinar la elegibilidad.

La elegibilidad para los subsidios para ayudar a pagar las primas de los planes de seguro vendidos en los mercados establecidas por la Ley de Cuidado de Salud a Bajo Precio (ACA) también está vinculada al nivel oficial de pobreza.

Uno de cada ocho estadounidenses depende del Programa de Asistencia Nutricional Suplementaria, o cupones de alimentos, y el 40% de los recién nacidos y sus madres reciben alimentos a través del programa Mujeres, Bebés y Niños, que también utilizan el nivel federal de pobreza para determinar la elegibilidad.

Los ex empleados de la oficina dijeron que no fueron desleales al presidente. Sabían que sus trabajos les exigían seguir los objetivos de la administración. “Intentábamos apoyar el programa de MAHA”, dijo el científico social, refiriéndose a “Make America Healthy Again” (Hacer que Estados Unidos Vuelva a Ser Saludable) de Kennedy. “Aunque no se alineara con nuestras visiones personales del mundo, queríamos ser útiles”.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

More Psych Hospital Beds Are Needed for Kids, but Neighbors Say Not Here

If you or someone you know may be experiencing a mental health crisis, contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by dialing or texting “988.” In January, a teenager in suburban St. Louis informed his high school counselor that a classmate said he planned to […]

Rural Health

If you or someone you know may be experiencing a mental health crisis, contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by dialing or texting “988.”

In January, a teenager in suburban St. Louis informed his high school counselor that a classmate said he planned to kill himself later that day.

The 14-year-old classmate denied it, but his mother, Marie, tore through his room and found a suicide note in his nightstand. (She asked KFF Health News to publish only her middle name because she does not want people to misjudge or label her son.)

His parents took him to Mercy Hospital St. Louis. According to his mother, providers told them they didn’t have beds available at their behavioral health center, so the teen spent three days in a room in a secured area of the emergency department and saw a doctor twice, one time virtually.

Joe Poelker, a Mercy hospital spokesperson, declined to answer questions from KFF Health News. Leaders of Mercy and other local hospitals have described the shortage of beds for inpatient pediatric psychiatric care in the St. Louis area as a crisis for years.

Nationwide, psychiatric “boarding” — when a patient waits in the emergency room after providers decide to admit the person — has increased because of a rise in suicide attempts, among other mental health issues, and a shortage of inpatient psychiatric beds, according to a study of 40 hospitals in the journal Pediatrics. It found the number of cases in which children spent at least two days in pediatric hospitals before being transferred for psychiatric care also increased 66% from 2017 through 2023 to reach 16,962 instances.

St. Louis Children’s Hospital leaders aim to address that problem by opening a 77-bed pediatric mental health hospital in the suburb of Webster Groves. But as often happens with such proposals, neighbors objected. They worry it would worsen safety and lower property values.

Over the past decade, proposed psychiatric facilities for minors in California, Colorado, Iowa, Nebraska, and New York have also faced local resistance.

Behavioral health care advocates counter that such concerns are largely unfounded and rooted in stigma. Locating such facilities in remote areas — as neighbors sometimes suggest — reinforces the misconception that people with mental illness are dangerous and makes it harder to help them without their support system nearby, doctors say.

“We wouldn’t take children with cancer and say they need to be two hours away, where there is no one around them,” said Cynthia Rogers, a pediatric psychiatrist at St. Louis Children’s. “These are still children with illnesses, and they want to be in their home city, where their family can visit them.”

In the United States, the number of suicides among minors increased 62% from 2002 to 2022, according to a KFF analysis of data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

At St. Louis Children’s, the crisis has fueled more emergency room visits, Rogers said, with behavioral health visits nearly quadrupling from 2019 to 2023, jumping from 565 to 2,176. She attributes the increase to factors such as social media engagement, isolation caused by shutdowns during the covid-19 pandemic, and the political climate, which she said has been particularly hard on LGBTQ+ children.

“The pandemic seemed to throw gasoline on the fire,” Rogers said.

In the middle- and upper-class suburb of Webster Groves, St. Louis Children’s and KVC, a behavioral health provider, want to use a site that served as an orphanage in the 19th century to create 65 inpatient beds for children needing care for about a week and 12 residential beds for people requiring longer stays. KVC now runs a school there for students who struggle in traditional classrooms and offers services to help children in foster care.

“Introducing a hospital into this historically significant residential area disrupts its stability by undermining” its character, one resident testified at a January City Council meeting.

Tim Conway, who has lived across from the site for three decades, told KFF Health News that his opposition is primarily because the facility and its parking would take up more space than the existing structures.

The detailed security plans have not eased his concerns. “It makes me wonder why it needs to be that robust,” Conway said.

Samer El Hayek, a psychiatrist at the American Center for Psychiatry and Neurology in the United Arab Emirates, has studied how stigma impacts the locations of psychiatric facilities around the world and said people often don’t want the hospitals nearby because they associate them with violence or unpredictable behavior.

“The misconception of increased danger often stems from outdated stereotypes rather than factual evidence,” El Hayek said.

Little evidence suggests that people with mental illness are more likely to commit a crime or be violent than the general population, with the exception of people with a severe illness such as schizophrenia, who, while it’s still rare, are likelier to commit a violent act.

But residents near mental health hospitals have been rattled by encounters with patients who escaped or reports from law enforcement and local news about missing patients.

In Oklahoma City, Richard Scroggins in 2014 opposed the expansion of Cedar Ridge Behavioral Hospital, which then treated youths and adults, because of its security issues.

Scroggins, who raises horses and cattle on his property, told The Oklahoman newspaper at the time that he once found a stranger raking leaves in his yard. After determining the person was suffering from mental illness and harmless, Scroggins said, he called the police, who retrieved the person.

The Cedar Ridge provider ultimately dropped plans to expand the facility after community opposition.

Scroggins has since encountered other patients from the facility on his property but none in recent years, he told KFF Health News in February. His perspective on the hospital has changed because its staff addressed his security concerns.

“Nobody wants it in their neighborhood, but it’s a necessity,” Scroggins said. “I’m a Christian, so we are supposed to reach out and help.”

Carrie Blumert, CEO of the Mental Health Association Oklahoma, said psychiatric facilities make surrounding areas safer by providing medical care and “treating the root of people’s issues rather than just throwing them in a jail cell.”

In Marie’s case, her son was ultimately admitted to Mercy-affiliate Hyland Behavioral Health Center and spent a few days there until a physician told the family he probably just needed to speak with a counselor, she said. He was discharged.

A day later, she said, the teen said he still wanted to kill himself, so his parents took him to St. Louis Children’s, where he was admitted the same day. After a 15-minute visit, Marie said, a doctor pulled her aside and asked, “Have you ever thought that he might be on the autism spectrum?”

“‘Oh my gosh, you’re the first person to validate my feeling,’” Marie told the doctor.

Her son stayed two weeks at the hospital, during which providers diagnosed him with autism and prescribed antidepressants. He returned to the classroom and baseball field, Marie said, but learning he has autism upset him.

“He’s still trying to process that, and he’s very sensitive. And they are teenagers, so when kids are mean to him at school or make fun of him, he takes that to heart way more than a typical teenager would,” Marie said. “I have hope for him that he will be OK.”

And soon, she knows, kids like her son could have another option in St. Louis if they need acute psychiatric help.

Despite community pushback, the Webster Groves City Council unanimously approved the rezoning needed for the hospital in January. The officials described opponents’ concerns as legitimate but said the hospital would benefit children’s mental health and the surrounding community.

“This is by far and away one of the easiest votes I’ve ever had to take,” said Councilmember David Franklin, adding that the approval demonstrates that “Webster Groves cares not only about its own citizens but the citizens of this region.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).