Trump Policies at Odds With ‘Make America Healthy Again’ Push

In his March address to Congress, President Donald Trump honored a Texas boy diagnosed with brain cancer. Amid bipartisan applause, he vowed to drive down childhood cancer rates through his “Make America Healthy Again” initiative. A few days later, the administration quietly dropped a lawsuit […]

Health Care

As Republicans Eye Sweeping Medicaid Cuts, Missouri Offers a Preview

CRESTWOOD, Mo. — The prospect of sweeping federal cuts to Medicaid is alarming to some Missourians who remember the last time the public medical insurance program for those with low incomes or disabilities was pressed for cash in the state. In 2005, Missouri adopted some […]

Health Care

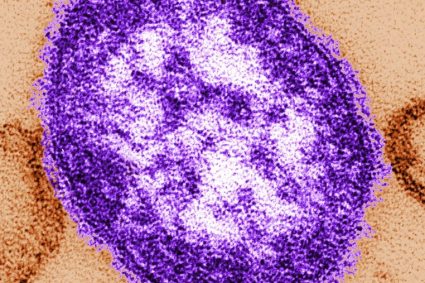

Nova Scotia resident becomes province’s 1st measles case in 2 years after U.S. visit

Public health has released a list of possible exposure locations in downtown Halifax, including a hotel, a bar and the Halifax Infirmary ER.

Measles

Alberta Medical Association warns measles will rise, says ramped-up health campaign needed

Alberta Medical Association president Dr. Shelley Duggan says the numbers suggest that within weeks, the numbers could skyrocket.

MeaslesAlberta Medical Association president Dr. Shelley Duggan says the numbers suggest that within weeks, the numbers could skyrocket.

Transplant recipients and other immunocompromised people worry about measles exposure

Laurie Miller, a heart transplant patient exposed to measles in Stratford, Ont., says her story speaks to the risks people who are immunocompromised face during an outbreak.

MeaslesLaurie Miller, a heart transplant patient exposed to measles in Stratford, Ont., says her story speaks to the risks people who are immunocompromised face during an outbreak.

Moms in Crisis, Jobs Lost: The Human Cost of Trump’s Addiction Funding Cuts

When the Trump administration cut more than $11 billion in covid-era funds to states in late March, addiction recovery programs suffered swift losses. An Indiana organization that employs people in recovery to help peers with substance use disorders and mental illness was forced to lay […]

Health CareWhen the Trump administration cut more than $11 billion in covid-era funds to states in late March, addiction recovery programs suffered swift losses.

An Indiana organization that employs people in recovery to help peers with substance use disorders and mental illness was forced to lay off three workers. A Texas digital support service for people with addiction and mental illness prepared to shutter its 24/7 call line within a week. A Minnesota program focused on addiction in the East African community curtailed its outreach to vulnerable people on the street.

Although the federal assistance was awarded during the covid-19 pandemic and some of the funds supported activities related to infectious disease, a sizable chunk went to programs on mental health and addiction. The latter are both chronic concerns in the U.S. that were exacerbated during the pandemic and continue to affect millions of Americans. Colorado, for example, received more than $30 million for such programs and Minnesota received nearly $28 million, according to health and human services agencies in those states.

In many cases, this money flowed to addiction recovery services, which go beyond traditional treatment to help people with substance use disorders rebuild their lives. These programs do things that insurers often don’t reimburse, such as driving people to medical appointments and court hearings, crafting résumés and training them for new jobs, finding them housing, and helping them build social connections unrelated to drugs.

A federal judge temporarily blocked the Trump administration’s cuts, allowing the programs to continue — for now — receiving federal funding. But many of the affected programs say they can’t easily rehire people they laid off or resurrect services they curtailed. And they’re unsure they can survive long-term amid an environment of uncertainty and fear, not knowing when the judge’s ruling might be lifted or another funding source cut.

The week it slashed the funding, the Trump administration also announced a massive reorganization of the Department of Health and Human Services, including the consolidation of the main federal agency focused on addiction recovery services. Without a stand-alone office like the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, many advocates worry, recovery work — and the funding to support it — will no longer be a priority. Although private foundations and state governments may step in, it’s unlikely they could match the tranches of federal funding.

“Recovery support is treated as optional,” said Racquel Garcia, founder of HardBeauty, a Colorado-based addiction recovery organization.

The federal cuts put at risk a roughly $75,000 grant her team had received to care for pregnant women with substance use disorders in two rural counties in Colorado.

“It’s very easy to make sweeping decisions from the top in the name of money, when you don’t have to be the one to tell the mom, ‘We can’t show up today,’” Garcia said. “When you never have to sit in front of the mama who really needed us to be there.”

Mental health conditions, including substance use disorders, are a leading cause of maternal mortality in the U.S. And although national overdose deaths have decreased recently, rates have risen in many Black and Native American communities. Many people in the addiction field worry these funding rollbacks could reverse hard-earned progress.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services spokesperson Emily Hilliard told KFF Health News that the department is reorganizing to improve efficiency, foster a more coordinated approach to addiction, and prioritize funding projects that align with the president’s Make America Healthy Again initiative.

“We aim to streamline resources and eliminate redundancies, ensuring that essential mental health and substance use disorder services are delivered more effectively,” she said in a statement.

But to Garcia, it doesn’t feel like streamlining. It feels like abandoning moms in need.

Between the time the cuts were announced and when the federal judge paused them, two women served by Garcia’s program gave birth, she said. Though her grant funding was in limbo, Garcia told her employee to show up at the bedside for both moms. The employee followed up with daily check-ins for the new moms, connected them to treatment or housing services when needed, and helped them navigate the child services system.

“I just can’t leave moms” without services, Garcia said. “I just can’t do it.”

Nor can she abandon that employee, she said. Although the federal funding provided half of that employee’s salary, Garcia has continued to keep her on full time.

Garcia said she primarily employs women in recovery, many of whom spent years trapped in abusive situations, relying on welfare benefits. Now they’re sober and have found meaningful work that allows them to provide for their families, she said. “We created our own workforce of mamas who help other mamas.”

This type of recovery workforce development seems to align with the Republican Party’s goals of getting more people to work and reducing reliance on welfare benefits. The Trump administration’s drug policy priorities, released in early April, identified creating “a skilled, recovery-ready workforce” and strengthening peer recovery support services as crucial efforts to help people “find recovery and lead productive, healthy lives.” Many recovery programs train people for blue-collar jobs, which could support Trump’s goal of reviving the manufacturing industry.

But the administration’s actions appear to conflict with its stated goals, said Rahul Gupta, the nation’s drug czar during the Biden administration.

“You can’t have manufacturing if people can’t pass a urine drug test or continue to suffer from addiction or relapse,” said Gupta, who is now president of GATC Health, a company using artificial intelligence for drug development.

Even if jobs return to rural America, cutting funding for recovery services and the main federal office overseeing such efforts could mean fewer people are employable, Gupta said.

Research on recovery programs, particularly those run by people with personal addiction experience, suggests they can increase engagement in court-ordered treatment, reduce the prevalence of rearrest, bolster attendance at treatment appointments, and improve the likelihood of families reunifying and stabilizing.

Billy O’Bryan sees these benefits daily. As a state director for the national nonprofit Young People in Recovery, O’Bryan oversees about a dozen chapters in Kentucky that teach people in recovery life skills, such as balancing a checkbook and interviewing for jobs, and show them how to have fun in sobriety, through group hikes and glow-in-the-dark Ultimate Frisbee games.

Providing recovery services “is when we really invest in their future,” said O’Bryan, who is in recovery too.

Six of his chapters were affected by the federal funding cuts. That has meant dipping into his organization’s rainy day fund to pay staff and cutting back on community events, including cleanup days in which chapter members gather used syringes off the street, pass out the overdose reversal medication naloxone, and talk to people using drugs about the possibility of recovery.

He’s exploring fundraising efforts now, but not all his chapters have the same ability.

“In a city like Louisville, fundraising is not a problem,” O’Bryan said, “but when you get out into Grayson, Kentucky” — a rural area in the Appalachian Mountains — “there’s not a lot of opportunities.”

In Minnesota, Kaleab Woldegiorgis and his colleagues at Niyyah Recovery Initiative used to spend hours a day at soup kitchens, community events, mosques, and on the streets of East African and Muslim neighborhoods, trying to connect with people using drugs. They spoke Somali, Amharic, and Swahili, among other languages.

Those outreach efforts allowed them to “find individuals in need of recovery services” who “weren’t seeking it out themselves,” said Woldegiorgis, who previously attended Niyyah’s support groups when he was dealing with addiction.

After building relationships with people, Woldegiorgis could help them connect with formal recovery services that bill their insurance, he said. But help couldn’t always wait for a contract.

One afternoon shortly before the federal funding cuts, Woldegiorgis and his colleagues spoke with a man who began weeping, recounting how he had wanted to get treatment a few days earlier but had lost his belongings, returned to using drugs, and ended up on the street. Woldegiorgis said he helped the man reconnect with a sister and begin exploring treatment options.

With the federal funding cuts, Niyyah may no longer be able to support this type of outreach work. Woldegiorgis fears it means people won’t receive the message of hope that can come from interacting with role models in recovery.

“People don’t pick up pamphlets to receive these messages. And people don’t read emails and people don’t look at billboards and find inspiration,” he said. “People need people.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

El costo humano de los recortes de Trump a los programas de tratamiento de adicciones

Cuando la administración Trump recortó a finales de marzo más de $11.000 millones en fondos estatales destinados a la era de covid-19, los programas de recuperación de adicciones sufrieron pérdidas rápidas. Una organización de Indiana que emplea a personas en recuperación para ayudar a compañeros […]

Health CareCuando la administración Trump recortó a finales de marzo más de $11.000 millones en fondos estatales destinados a la era de covid-19, los programas de recuperación de adicciones sufrieron pérdidas rápidas.

Una organización de Indiana que emplea a personas en recuperación para ayudar a compañeros con trastornos por adicciones y afecciones mentales se vio obligada a despedir a tres trabajadores. Un servicio de apoyo digital en Texas para personas con las mismas problemáticas se preparó para cerrar su línea telefónica 24/7 en una semana. Un programa de Minnesota centrado en la adicción en la comunidad de África Oriental restringió su alcance a personas vulnerables que viven en las calles.

Aunque la asistencia federal se otorgó durante la pandemia de covid y algunos de los fondos apoyaron actividades relacionadas con enfermedades infecciosas, una parte considerable se destinó a programas de salud mental y adicciones.

Estas últimas son preocupaciones crónicas en Estados Unidos que se agravaron durante la pandemia y siguen afectando a millones de estadounidenses.

Colorado, por ejemplo, recibió más de $30 millones para estos programas y Minnesota casi $28 millones, según las agencias de salud y servicios humanos de esos estados.

En muchos casos, este dinero se destinó a servicios de recuperación de adicciones, que van más allá del tratamiento tradicional para ayudar a las personas con adicciones a reconstruir sus vidas. Estos programas realizan tareas que las aseguradoras a menudo no reembolsan, como llevar a las personas a citas médicas y audiencias judiciales, preparer currículums y capacitarlas para nuevos empleos, encontrarles alojamiento y ayudarlas a establecer vínculos sociales no relacionados con las drogas.

Un juez federal bloqueó temporalmente los recortes de la administración Trump, lo que permitió que, por ahora, los programas siguieran recibiendo fondos federales. Sin embargo, muchos de los afectados afirman que no pueden recontratar fácilmente a las personas que despidieron ni reactivar los servicios que redujeron.

Además, no están seguros de poder sobrevivir a largo plazo en un entorno de incertidumbre y temor, sin saber cuándo se revocará el fallo del juez o se recortará otra fuente de financiamiento.

La semana en que se recortaron drásticamente los fondos, la administración Trump también anunció una reorganización masiva del Departamento de Salud y Servicios Humanos (HHS), que incluye la consolidación de la principal agencia federal dedicada a los servicios de recuperación de adicciones. Sin una oficina independiente como la Administración de Servicios de Abuso de Sustancias y Salud Mental, muchos defensores temen que el trabajo de recuperación, y el dinero para apoyarlo, ya no sea una prioridad.

Aunque fundaciones privadas y gobiernos estatales podrían intervenir, es poco probable que puedan igualar las sumas de financiación federal.

“El apoyo a la recuperación se considera opcional”, dijo Racquel García, fundadora de HardBeauty, una organización de recuperación de adicciones con sede en Colorado.

Los recortes federales ponen en riesgo una subvención de cerca de $75.000 que su equipo había recibido para atender a mujeres embarazadas con adicciones en dos condados rurales de Colorado.

“Es muy fácil tomar decisiones drásticas desde arriba por dinero, cuando no tienes que ser quien le diga a la madre: ‘No podemos ir hoy’”, dijo García. “Cuando nunca tienes que sentarte frente a la madre que realmente necesitaba que estuvieras allí”.

Las afecciones de salud mental, incluidos los trastornos por consumo de sustancias, son una de las principales causas de mortalidad materna en el país. Y, aunque las muertes por sobredosis a nivel nacional han disminuido recientemente, las tasas han aumentado en muchas comunidades afroamericanas y nativas americanas. A muchas personas en el campo de las adicciones les preocupa que estos recortes de fondos puedan revertir el progreso logrado con tanto esfuerzo.

Emily Hilliard, vocera del HHS, declaró a KFF Health News que el departamento se está reorganizando para mejorar la eficiencia, fomentar un enfoque más coordinado para la adicción y priorizar la financiación de proyectos que se alineen con la iniciativa presidencial Make America Healthy Again.

“Nuestro objetivo es optimizar los recursos y eliminar las redundancias, garantizando que los servicios esenciales de salud mental y tratamiento de adicciones se presten de forma más eficaz”, dijo en un comunicado.

Pero para Garcia, no se siente como una mejora. Se siente como abandonar a madres necesitadas.

Entre el momento en que se anunciaron los recortes y cuando el juez federal los suspendió, dos mujeres atendidas por el programa de García dieron a luz, contó. Aunque la financiación de su subvención estaba en el limbo, García le dijo a su empleada que estuviera presente junto a las madres.

La empleada hizo seguimiento con visitas diarias a las nuevas mamás, las conectó con servicios de tratamiento o vivienda cuando fue necesario y las ayudó a navegar por el sistema de servicios infantiles.

“Simplemente no puedo dejar a las madres sin servicios”, dijo García. “Simplemente no puedo hacerlo”.

Tampoco puede abandonar a esa empleada, agregó. Aunque la financiación federal proporcionó la mitad de su salario, García la ha mantenido trabajando a tiempo completo.

García dijo que emplea principalmente a mujeres que están en proceso de recuperación, muchas de las cuales pasaron años atrapadas en situaciones de abuso, dependiendo de los beneficios sociales. Ahora están sobrias y han encontrado un trabajo significativo que les permite mantener a sus familias, dijo. “Creamos nuestra propia fuerza laboral de mamás que ayudan a otras mamás”.

Este tipo de desarrollo de la fuerza laboral en recuperación parece estar alineado con los objetivos del Partido Republicano de lograr que más personas trabajen y reducir la dependencia de la beneficencia.

Las prioridades de la política de drogas de la administración Trump, publicadas a principios de abril, identificaron la creación de “una fuerza laboral calificada y lista para la recuperación” y el fortalecimiento de los servicios de apoyo entre pares para la recuperación como esfuerzos cruciales para ayudar a las personas a “encontrar la recuperación y llevar una vida productiva y saludable”.

Muchos programas de recuperación capacitan a personas para empleos manuales, lo que podría respaldar el objetivo de Trump de revivir la industria manufacturera.

Sin embargo, las acciones de la administración parecen entrar en conflicto con sus objetivos declarados, dijo Rahul Gupta, quien fue el zar antidrogas durante la administración Biden.

“No se puede tener manufactura si las personas no pasan una prueba de drogas en orina o continúan sufriendo adicciones o recaídas”, afirmó Gupta, quien ahora preside GATC Health, una empresa que utiliza inteligencia artificial para el desarrollo de fármacos.

Incluso si Vuelve a haber más empleos en las zonas rurales de Estados Unidos, recortar la financiación de los servicios de recuperación y de la principal oficina federal que supervisa estos esfuerzos podría significar que menos personas sean “empleables”, afirmó Gupta.

Las investigaciones sobre programas de recuperación, en particular los dirigidos por personas con experiencia personal en adicciones, sugieren que pueden aumentar la participación en el tratamiento ordenado por el tribunal, reducir la prevalencia de reincidencia, fomentar la asistencia a las citas de tratamiento y mejorar la probabilidad de reunificación y estabilización familiar.

Billy O’Bryan ve estos beneficios a diario. Como director estatal de la organización nacional sin fines de lucro Young People in Recovery, O’Bryan supervisa cerca de una docena de filiales en Kentucky que enseñan a personas en recuperación habilidades para la vida, como manejar una cuenta bancaria y presentarse a entrevistas de trabajo, y les muestran cómo divertirse en sobriedad, mediante caminatas en grupo y juegos de Ultimate Frisbee que brillan en la oscuridad.

Brindando servicios de recuperación “es cuando realmente invertimos en su futuro”, dijo O’Bryan, quien también está en recuperación.

Seis de sus capítulos se vieron afectados por los recortes de fondos federales. Por eso ha tenido que recurrir al fondo de emergencia de la organización para pagar al personal, y reducir los eventos comunitarios, incluyendo las jornadas de limpieza en las que los miembros del capítulo recogen jeringas usadas de la calle, distribuyen naloxona, el medicamento para revertir sobredosis, y hablan con personas que consumen drogas sobre la posibilidad de recuperarse.

Actualmente está explorando iniciativas de recaudación de fondos, pero no todos sus capítulos tienen la misma capacidad.

“En una ciudad como Louisville, recaudar fondos no es un problema”, dijo O’Bryan, “pero cuando uno llega a Grayson, Kentucky”, una zona rural en los Apalaches, “no hay muchas oportunidades”.

En Minnesota, Kaleab Woldegiorgis y sus colegas de la Niyyah Recovery Initiative solían pasar horas al día en comedores sociales, eventos comunitarios, mezquitas y en las calles de barrios musulmanes y África Oriental, intentando conectar con personas que consumen drogas. Hablaban somalí, amárico y suajili, entre otros idiomas.

Esas iniciativas de divulgación les permitieron encontrar personas que necesitaban servicios de recuperación y que no los buscaban por sí mismas, afirmó Woldegiorgis, quien anteriormente asistió a los grupos de apoyo de Niyyah cuando él mismo lidiaba con la adicción.

Tras construir relaciones con las personas, Woldegiorgis podía ayudarlas a conectarse con servicios de recuperación formales que facturan a sus seguros, explicó. Pero la ayuda no siempre podía esperar a un contrato.

Una tarde, poco antes de los recortes de fondos federales, Woldegiorgis y sus colegas hablaron con un hombre que comenzó a llorar, contando cómo había querido recibir tratamiento unos días antes, pero había perdido sus pertenencias, había vuelto a consumir drogas y había terminado en la calle.

Woldegiorgis dijo que ayudó al hombre a reconectarse con una hermana y a comenzar a explorar opciones de tratamiento.

Con los recortes, es posible que Niyyah ya no pueda apoyar este tipo de trabajo comunitario. Woldegiorgis teme que esto signifique que las personas no recibirán el mensaje de esperanza que puede surgir al interactuar con personas que pueden ser sus modelos de recuperación a seguir.

“La gente no recoge folletos para recibir estos mensajes. Y la gente no lee correos electrónicos ni mira mensajes publicitarios en ls calles y encuentra inspiración”, dijo. “La gente necesita gente”.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Manitoba measles cases climb as vaccination rates fall

Driedger says public health messaging that is specific to each type of vaccine is more effective in helping vaccine-hesitant people make a decision.

MeaslesDriedger says public health messaging that is specific to each type of vaccine is more effective in helping vaccine-hesitant people make a decision.

Ontario Liberals call for urgent action to tackle ‘staggering’ measles outbreak

The latest data from Public Health Ontario shows the province has recorded 1,020 new measles since an outbreak began last October.

MeaslesThe latest data from Public Health Ontario shows the province has recorded 1,020 new measles since an outbreak began last October.

An Arm and a Leg: Winning a Two-Year Fight Over a Bogus Bill

In July 2022, “An Arm and a Leg” listener Meagan experienced a bout of vertigo that landed her in the emergency room. For more than two years after, Meagan endured what felt like a never-ending series of communications with the hospital over a medical bill […]

Health CareIn July 2022, “An Arm and a Leg” listener Meagan experienced a bout of vertigo that landed her in the emergency room. For more than two years after, Meagan endured what felt like a never-ending series of communications with the hospital over a medical bill she knew she didn’t owe.

Meagan spoke with host Dan Weissmann about what kept her motivated to keep fighting and the legal tactic that finally led to a breakthrough.

Dan Weissmann

Host and producer of “An Arm and a Leg.” Previously, Dan was a staff reporter for Marketplace and Chicago’s WBEZ. His work also appears on All Things Considered, Marketplace, the BBC, 99 Percent Invisible, and Reveal, from the Center for Investigative Reporting.

Credits

Emily Pisacreta, Claire Davenport

Producers

Adam Raymonda

Audio wizard

Ellen Weiss

Editor

Click to open the Transcript

Transcript: Winning a Two-Year Fight Over a Bogus Bill

Note: “An Arm and a Leg” uses speech-recognition software to generate transcripts, which may contain errors. Please use the transcript as a tool but check the corresponding audio before quoting the podcast.

Dan: Hey there–

A few months ago, we got a note from a listener named Meagan in California. It started like this:

“Last month, I successfully had a provider pull back a bill from collections and stop billing me for an ER visit from July 2022.

Meagan was writing to us in fall of 2024– that bill had not gotten resolved until more than two years after the ER visit.

Meagan, um, wanted to thank us! Her note said she’d picked up some tactical advice, but she said the show had helped her keep going. Here’s how she put it when we talked with her.

Meagan: I could listen to the podcast and kind of hear some community and say, I’m not alone. This is a possible thing, right?

Dan: Of course Meagan’s story is epic. Because parts of it are personal, she’s asked us not to use her full name.

This tale has some comically wild twists. And some important tactical lessons.

And it’s Meagan’s reflections on the whole journey that I especially want to share with you.

This is An Arm and a Leg, a show about why health care costs so freaking much, and what we can maybe do about it. I’m Dan Weissmann. I’m a reporter, and I like a challenge. So the job we’ve chosen on this show is to take one of the most enraging, terrifying, depressing parts of American life, and bring you something entertaining, empowering, and useful.

July 28, 2022 was a Thursday. Meagan woke up to a brand new experience: Vertigo. Nausea. Dizzyness, the works.

Meagan: I just couldn’t see straight, couldn’t stand up… basically made it to the bathroom and laid on the bathroom floor for like four hours.

Dan: She called in sick to work, waited to feel better. But she didn’t. And she got frightened.

Meagan: I think what was scariest about it is that I didn’t know why I had it. What if I have a brain tumor and that’s why I can’t see straight, or like, what if something’s going on with my eyes?

Dan: Meagan lives alone.

Meagan: So like the number of people that you want to call in that situation, that are like, ‘hi, can you like, help me?’

Dan: That number was zero.

She called an ambulance, went to the closest hospital.

The ER docs ruled out the scariest possibilities, gave her meds for dizziness and nausea, sent her home. And she recovered.

That was the easy part. On to the bills.

The fight over the first bill was really kind of a warm-up. This one arrived a couple months after her ER visit, from the ambulance service. Two thousand, seven hundred twenty-two dollars and forty-two cents.

Which Meagan did not expect to pay. She’d been to the ER earlier in the year, paid a whole lot of money — which she knew meant she’d hit her insurance plan’s out-of-pocket maximum.

Every insurance plan has this: It’s the number that, after you hit it, insurance picks up everything else.

So she called her insurance company.

Meagan: I was like,‘Hey, I’ve hit my out of pocket max. This doesn’t make any sense. I’m getting billed.’ And they kind of said,‘Okay, yeah, we’re on it. We’ll handle it. We’ll reprocess everything.’

Dan: And she did get paperwork from her insurance that said she owed the ambulance company nothing.

But she kept getting bills. And after a few months, a collection agency called about them. Meagan says she told them: My insurance company says I don’t owe this.

And she says their response was, Well, do you have documentation?

Meagan: And they said it in this tone that was like, you don’t know what you’re talking about and you can’t be right. Here’s a very specific document that you’re gonna need to prove this. And I was like, Yeah, I have that.

Dan: You may have caught a second person laughing there. That’s our producer Claire Davenport, who talked with Meagan and did most of the reporting for this story. Meagan says she emailed the collections folks right away.

Meagan: I was like,‘per our discussion, here is all the documents that say, I do not owe you any money.’ And then they said,‘okay,’ and I never heard from them again.

Dan: So, Meagan was like, OK cool! That totally worked.

But like I mentioned: That ambulance bill was just the warmup.

By the time it got resolved, it was March 2023, almost eight months after her vertigo attack. Meagan says the hospital still hadn’t sent her a bill for the actual ER visit.

But she had gotten documents from her insurance company, United Healthcare. They show that United had paid the hospital, run by Kaiser Permanente, a few thousand dollars.

By the way: We know all this because Meagan shared dozens of pages of paperwork with us

United seemed to think Meagan would owe Kaiser about five hundred seventy dollars..

Meagan says she finally heard from Kaiser in July 2023. Just short of a year since her ER visit. They sent a bill for three thousand, three hundred eight-one dollars and 62 cents. This is almost six times United’s estimate.

Meagan: I’m like, this is a massive amount of money. I know I don’t owe it. What is going on?

Dan: Getting that resolved would take more than 15 months. And a lot of phone calls. From the start, she says she kept in mind tips from this show.

Meagan: One of the things that y’all talk about on the podcast is just having that, like, pretty cordial tone, like not getting angry at the people. So every time I’m calling, like I’m frustrated, I’m tired, but I’m having a pleasant conversation with the person on the other end of the line who is not personally responsible for what’s going on.

Dan: Here’s how she says those conversations tended to go.

Meagan: I’d call United and I’d say,‘Hey, United. This provider is billing me. Can you guys reprocess this claim?’ And they would say,‘yep, we’re on it. We see your file.’

Dan: And by the time Meagan says she started making these calls United’s file showed Meagan only owed Kaiser about sixty-four bucks. Meagan says United would promise to tell Kaiser the deal.

Meagan: I would also immediately call Kaiser and say,‘Hey, Kaiser. I just spoke to United. I’m protesting this claim. Please do not keep billing me.’

Dan: And so on.

Meagan: Every single person that I talked to was trying to be helpful. Everyone was like, Oh yeah, like, I’ve looked through your notes, this looks like a mistake.

Dan: She says, they’d tell her, just give us 10 to 14 business days to process this.

Meagan: And then I would just go on with my life.

Dan: But month after month, she says: those fixes just did not stick.

Meagan: And so every time I got a bill, it was like, this person failed me. Like they weren’t able to do this and get it fixed for me. And it was just

super-disappointing. And I was like, I’m back in exactly the same position. Like, I didn’t feel like I had any other tools.

Dan: But she found ways to keep going, make the next call. Like remembering how she’d fought off the ambulance bill.

Meagan: I was like, okay, I’m so confident that I do not owe this because I have been successful before And so that would get me, like, really amped up and angry about it.

Dan: That was one kind of energy. Meagan says she also got a lot of support and inspiration from her best friend.

Meagan: Her mom had recently had to go in for knee surgery. Dan: And some of the bills, they hadn’t looked right to Meagan’s friend.

Meagan: And her mom doesn’t speak a lot of English. She’s not very high income. So she’s got a lot fewer privileges than my friend or myself. And so my friend is the one who took on the responsibility of her bills. And so my friend was really helpful in that because we would talk about, like, it’s the principle of it for the people who can’t do this.

Dan: Meagan says that principle gave her a different kind of energy: It let her imagine that there might be a bigger point to her fight.

Meagan: Maybe if I can fight this, they can find some issue that this won’t happen again and it won’t happen to somebody else.

Dan: And Meagan knew: This was happening to a lot of other people.

Meagan: People have been fighting for harder stuff. People have had harder or longer chronic conditions, I was healthy, right? It’s not like I was fighting cancer bills or different providers or just the complexity that billing can get into. And I feel like your show was part of that inspiration for me where it’s like people out there are going through tougher things than just a single hospital visit where one bill is wrong. And so, yeah, I can keep doing this. This is easy.

Dan: So month after month, Meagan says she just kept making that next call. And after a while, she tried some new tactics.

An Arm and a Leg Season 13, Episode 5 3/20/25 p.6

After she got a bill dated December 24 — Christmas eve — she tried something new:

She sent Kaiser a fax of the statement from her insurance saying she owes 64 dollars, not three thousand.

And she says she called Kaiser to follow up. Got a guy on the phone.

Meagan: I was like, did you get and he was like, I can’t confirm that we’ve received it. It takes X amount of days.

Dan: By the time those days had passed, it was January 2025 — a year and a half after Meagan’s ER visit. She’d been fighting the bill for six months.

And by the end of January, yet another bill arrived.

So… Meagan thinks it’s around this time when she tried to get Kaiser and United on the phone together herself. United had given her a number to pass along to Kaiser’s billing office.

Instead, this time Meagan got a Kaiser billing rep to stay on the line while Meagan started a three-way call.

But she says United didn’t want that three way call.

Meagan: They were like,‘Oh, the customer is on the line. You can’t use this phone number. Like this is only for businesses.’

Dan: No patients allowed. Meagan says United transferred the call to their customer-service line for patients.

There was a menu to navigate.. Meagan was used to it. The Kaiser rep, not so much.

Meagan: So we did the whole like click, you know, click number six click number one enter your you know Whatever and we’d maybe been on hold for like three or four minutes And she’s like,‘this is ridiculous. What are they doing? Why have we been here for so long?’ I’m like,‘ma’am, it’s been three minutes. Like, let me tell you what my life has been like lately. I was like, I know this music. I can tell you everything that’s coming.’

Dan: The problem did not get solved. Bills kept arriving. Meagan says she kept making calls.

And then in June, a United Healthcare rep gave Meagan a suggestion that turned things around.

That’s next.

This episode of An Arm and a Leg is produced in partnership with KFF Health News. That’s a nonprofit newsroom covering health issues in America. Their reporters win all kinds of awards every year. We are honored to work with them.

Meagan’s big call with a United Healthcare rep didn’t start with a very hopeful-sounding prognosis. She says the rep told her:

Meagan: ‘I don’t think there’s anything more that we can do, like we’ve. We’ve provided all this information to Kaiser. We don’t know why they’re getting it. We’ve followed all of their instructions.’

Dan: But she says the rep did have something to offer. Legal recourse — right in the paperwork United had sent Meagan:

Meagan: The United representative was like,‘Yeah, look at your explanation of benefits.’ There was language that she pointed out to me that said,‘you do not owe this bill and you have rights.’

Dan: And Meagan says the United rep told her about a free legal hotline. Meagan says she ended up talking with a lawyer who gave her a template for a Cease and Desist letter: A letter that says, if you don’t cut this out, I might sue you.

The template cited state and federal laws. Meagan filled in details about how Kaiser may be violating them — by billing her for money she didn’t owe. The letter demanded that they stop contacting her..

And it said how if they violated her rights– for instance, sending her another bill or calling her — the law gave her the right to sue for damages. Up to a thousand dollars for each instance.

Meagan sent her letter certified mail. She shared the receipt with us.

And, as she told Claire, this was actually the emotional high point of the whole epic.

Meagan: I was walking around and I was like telling a couple folks, I’m like,‘I just sent a cease and desist letter to Kaiser’ and they would be like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m so sorry,’ but for me, I was so excited. It’s the first point at which I felt that I had the power. Like, all of this situation the whole time along the way was like, I’m reliant on Kaiser. I’m reliant on United for these people to do things. And so that was flipping the script for me where I’m like, no, I’m a badass.

Dan: And then two months later, she got another bill. This one said FINAL NOTICE. It said if she doesn’t pay up, Kaiser will send her to collections.

So Meagan says she made the next phone call– and almost by accident — she found herself saying what turned out to be the magic words.

Meagan: I laugh at how I handled this because I called Kaiser, I said – it was a really, again, very cordial conversation. I was like, Hey, um, I sent you guys a cease and desist. Uh, I received another bill. Um, what’s going on? And they’re like,‘Not sure. Don’t have it in your file that we ever received anything. Don’t have any record of that here with this claim.’ I asked it as a question. This is what’s so funny to me. I was like,‘So like, do I have any other options than to sue y’all?’

Claire: That’s awesome. That’s the kindest way I’ve ever heard of someone threatening to sue.

Meagan: It’s so funny in retrospect, cause in the moment, it didn’t feel like a threat. It was just like. This is the next step, right? Like, I’ve done all the things that I’m supposed to do and it’s not working. And I think now we have to go to court. And that’s where Kaiser came back and was like, no, no, no, no, no. Like, we don’t, we don’t have to go to court. They immediately were like,‘I’m going to go ahead and transfer you to someone.’

Dan: Meagan says the woman she talked to — “Angie” in her notes — seemed to take her seriously.

Meagan: She was like, I will pull your letter out of collections. I will call you in three days. And it was just after that, everything was boom, boom, boom, boom, boom

Dan: It took a few weeks. Meagan says Angie kept giving her status reports.

Meagan: until finally one day I got the call and she was like,‘It’s done. It’s settled. You owe us 64 dollars,’ which is like, a huge win, but also I was like, could I also not pay that 64 dollars at this point?

Dan: Not quite. Meagan says Angie transferred her to someone who would take that sixty-four dollar payment.

Meagan: And she goes,‘Is this hospital visit from 2022?’ She was shocked. She was like,‘this might be the oldest bill that I’ve ever processed.’ Like, I was like,‘yeah.’

Dan: So, it’s done.

We asked both United and Kaiser about Meagan’s story. They responded by email. United said they were glad their staff were ultimately able to help.

Kaiser said Meagan’s “experience was unusual, and should not have happened. It was understandably frustrating for her, and we offer our apology.”

Kaiser also blamed United for everything. They said ALL the bills they sent Meagan “were based on incorrect information from her insurer, which repeatedly provided us with wrong amounts for the patient’s responsibility, all while providing different information to the patient.”

Which conflicts with Meagan’s recollections, and the documents she shared with us.

For instance, there’s paperwork Meagan got from United saying, basically, “Hey, just FYI — here’s a copy of a letter we just sent Kaiser.” That letter shows Meagan’s responsibility as being — exactly the amount Kaiser ultimately accepted. OK.

Meanwhile, Meagan is definitely still working through her feelings about the whole thing.

One of them is actually disappointment. Meagan says that one of the things that kept her going was the hope that she could help Kaiser identify a systemic problem, and fix it.

By the end, it wasn’t really about the money.

After the first six months, Kaiser actually reduced the amount they were billing her for — Meagan says she still doesn’t know why — from three thousand and some dollars, to five hundred and some, which she says she could have paid, no problem.

Meagan: 500 for me was easy. But I know it’s not for someone else and that’s where I would always like pull back that strength and be like,‘this is all about an opportunity to get something fixed.’ I want this to not happen to other people. I mean, it’s, it’s almost a little bit of a pipe dream to hope that that’s going to happen, but I know for a fact it never happened because one person handled my case, and then that was it.

Dan: So disappointment is one feeling. Another one is fear.

Meagan says she may be more scared now than when she was fighting the bill. She compares it to the day she called the ambulance, her vertigo attack.

Meagan: I almost didn’t have the mental capacity on that day to be scared. Everything that I did that day was about putting one foot in front of the other. I was like, okay, like, this is not good. I have to get to the hospital. If I have to get to the hospital, like, I need to call an ambulance. If I need to call an ambulance, I need to find out where my phone is. Okay, I’ve gotten to my phone. But if I call an ambulance, my front door is locked. And I really – I don’t want them to break my door down. I, like, crawled to my front door to unlock it and I just laid it in my front door until the EMTs were there, right? That progression that I just told you probably took about six hours, right? Like, it was just terrible but I didn’t have time to be scared.

Dan: Meagan says while she was actually fighting the bill, she was just taking the next step, each time.

Meagan: The scary part for me is actually today. Like, I don’t actually – I don’t believe that it’s over. I am still scared that I’m going to get another bill in the mail, that they’re going to make some other mistake that says, Oh no, she still owes this money. And I don’t know when that ends.

Dan: Meagan says she asks herself if she would do it all again. And given the disappointment, all the work, and even the fear she still carries– she’s not sure.

Meagan: it’s hard in retrospect to know if any of it was worth it ‘cause I could have just paid 500 and never thought about it again. And that’s really, really hard to wrestle with.

Dan: But she’s not sure she WOULDN’T do it again. She’s definitely got things she’s learned to appreciate. Like consumer-protection laws.

Meagan didn’t learn about some of her rights until a United Healthcare worker pointed them out. But they were printed on the paperwork she’d been getting every month.

Meagan: When push came to shove, it was written right there, and you could point to it. And someone somewhere in California fought for that and made that a law. And I don’t know who they are, but like every little element of that law coming through to support me, I’m very thankful for because it helped me so much.

Dan: And as Meagan told my colleague Claire, when friends mention medical bills they’re fighting, she likes to encourage them.

Meagan: I like to tell my friends the story of like, oh, I fought a medical bill and I And I kind of just leave it at that, right? I want to give them the fact like there is a data point that says sometimes you can fight medical bills successfully. And if you need to talk about anything like I’m here for you,

Claire: We should create like a little badge saying, I fought a medical bill and I won or something like that. Like a little, like, I’m thinking of like a Girl Scout badge, like something you could put on your backpack.

Meagan: Exactly.

Claire: Like iron-on

Meagan: Like, ask me about fighting medical bills.

Claire: I love that idea. That’s something we should totally do. I’m going to tell Dan about that.

Dan: I love it too! This is what I especially love about Meagan’s story: Meagan says our show encouraged her to take action and to keep going. And now she wants to give encouragement to other people.

And: A friend of mine pointed out one time what’s so cool about the word encouragement.

Break it down, en-courage — it’s like, filling someone up with COURAGE. It makes me so happy to think that this show encouraged Meagan. It makes me encouraged. That is what I want to keep going, keep passing along.

Of course, I also want to share some of the tools that Meagan discovered along the way.

For starters, there’s the sample cease-and-desist letter that lawyer shared with her. Some of the laws it cites are California-specific. But California’s a big state, maybe you live there!

Wherever you live, you’ll have some of your own work to do, making sure the circumstances there apply to you. I’m not a lawyer, and we don’t give legal advice here. But this is a darned interesting place to start!

I also want to shout out a hack that Meagan developed: Using the notes app on her phone to make a cheat-sheet that she’d always have with her.

Meagan: I did most of these phone calls from work. And so what I realized is, oh, the bills at home. And I have an account number and it’s written on the bill. And I don’t know how to find that while I’m at my office or just like walking around, taking a phone call.

Dan: So she made a place for them, on her phone. That’s a tip I definitely intend to copy. We’ll share more take-aways in our first aid kit newsletter — if you’re not signed up, the place to go is arm and a leg show dot com, slash first aid kit.

And we’ll have a new episode for you in a few weeks. Till then, take care of yourself.

This episode of An Arm and a Leg was produced by Claire Davenport, with help from me, Dan Weissmann, and Emily Pisacreta

And edited by Ellen Weiss.

Adam Raymonda is our audio wizard.

Our music is by Dave Weiner and Blue Dot Sessions.

Bea Bosco is our consulting director of operations.

Lynne Johnson is our operations manager.

An Arm and a Leg is produced in partnership with KFF Health News. That’s a national newsroom producing in-depth journalism about health issues in America and a core program at KFF: an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism.

Zach Dyer is senior audio producer at KFF Health News. He’s editorial liaison to this show.

An Arm and a Leg is Distributed by KUOW– Seattle’s NPR station. And thanks to the Institute for Nonprofit News for serving as our fiscal sponsor. They allow us to accept tax-exempt donations. You can learn more about INN at INN.org.

Finally, thank you to everybody who supports this show financially. You can join in any time at arm and a leg show, dot com, slash: support. Thanks! And thanks for listening.

“An Arm and a Leg” is a co-production of KFF Health News and Public Road Productions.

For more from the team at “An Arm and a Leg,” subscribe to its weekly newsletter, First Aid Kit. You can also follow the show on Facebook and the social platform X. And if you’ve got stories to tell about the health care system, the producers would love to hear from you.

To hear all KFF Health News podcasts, click here.

And subscribe to “An Arm and a Leg” on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Medi-Cal Under Threat: Who’s Covered and What Could Be Cut?

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — Medi-Cal, California’s complex, $174.6 billion Medicaid program, provides health insurance for nearly 15 million residents with low incomes and disabilities. The state enrolls twice as many people as New York and more than three times as many as Texas — the two […]

Health CareSACRAMENTO, Calif. — Medi-Cal, California’s complex, $174.6 billion Medicaid program, provides health insurance for nearly 15 million residents with low incomes and disabilities. The state enrolls twice as many people as New York and more than three times as many as Texas — the two states with the largest number of Medicaid participants after California.

Enrollment is high because California goes beyond federal eligibility requirements, opening Medi-Cal to more low-income residents. The state also provides a broad range of benefits, such as vision, dental, and maternity care — some of which is largely paid for by federal dollars but which also affects state spending.

But lately, Medi-Cal has found itself in political crosshairs.

Democrats say the biggest threat to Medi-Cal is $880 billion in GOP budget cuts being mulled in Washington, D.C., which health experts say would require eligibility restrictions, such as work requirements, or program cuts to yield enough savings over a decade. Republicans argue that Medicaid costs have spiked due to fraud and abuse and they criticize state Democrats for making the benefit available to immigrants regardless of legal status.

In March, Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration borrowed $3.4 billion to cover an unexpected overrun in Medi-Cal, and lawmakers in April appropriated an additional $2.8 billion for the rest of the fiscal year. Although the Democratic governor acknowledged a need for adjustments, he has defended the state’s efforts to get more people covered. In 2022, California’s uninsured rate for residents under age 65 hit a record low of 6.2%, according to the California Health Care Foundation.

As lawmakers debate funding for the safety net program, here’s what’s at stake for California’s largest health program.

Who’s Covered?

More than a third of Californians depend on Medi-Cal or the closely related Children’s Health Insurance Program to see a doctor, therapist, or dentist. They rely on the program to get medicine and access treatment. It can also be a lifeline for families by allowing people with disabilities and seniors to stay in their homes and providing coverage to their caregivers. It also funds nursing care for seniors.

The overwhelming majority of enrollees qualify because they earn 138% or less of the federal poverty level: $21,597 annually for an individual person or $44,367 for a family of four. While that’s low for a state where the median household income tops $96,000, it’s far more generous than Alabama’s family eligibility limit, which is 18% of the federal poverty level, or Florida’s, at 26%.

Unlike Alabama or Florida, California extends coverage to low-income adults without dependents. The state also covers more people with disabilities who work, inmates, and other residents who wouldn’t qualify for the benefit program if California lawmakers hadn’t expanded the program beyond what the federal government requires.

According to state estimates, Medi-Cal covers about 7.3 million low-income families and an additional 5 million adults, most of whom don’t have dependents. An additional million people with disabilities rely on the program.

Medi-Cal also picks up the tab for 1.4 million residents 65 and older for benefits not covered by Medicare, such as long-term care and dental, hearing, and vision care.

The majority of adult Medi-Cal recipients under 65 work, according to a KFF review of March 2024 census data. In California, about 42% of nondisabled adults on Medi-Cal work full time and an additional 20% work part time. Those not employed were most commonly caring for a family member, attending school, or ill.

Just over half of Medi-Cal recipients are Latino, about 16% white, 9% Asian or Pacific Islander, and 7% Black, according to state enrollment data. That differs from the nation as a whole, where about 40% of people under age 65 who use Medicaid are white, 30% Hispanic, 19% Black, and 1% Indigenous people.

Where Does the Money Come From?

The federal government pays for about 60% of the Medi-Cal program. Of its nearly $175 billion budget this fiscal year, Washington, D.C., is expected to contribute $107.5 billion.

An additional $37.6 billion comes from the state’s general fund. The final $29.5 billion comes from other sources including hospital fees, a managed-care organization tax, tobacco tax revenue, and drug rebates.

California receives 50% in matching federal dollars for core services, such as coverage to children and low-income pregnant women. But it gets a 90% match for the roughly 5 million Californians it has added to rolls under the Medicaid expansion authorized by the Affordable Care Act.

Where Does It Go?

On average, Medi-Cal costs $8,000 per recipient, but costs vary widely, according to a March analysis by the California Legislative Analyst’s Office.

For instance, people with disabilities account for 7% of enrollees but 19% of Medi-Cal’s spending, with an average annual cost of $21,626.

Meanwhile, the cost to cover seniors averages roughly $15,000. And senior enrollment, at 1.4 million, has skyrocketed, increasing 40% since 2020 as lawmakers eased the rules for how many assets people 65 and older could have and still qualify for the program.

California also foots much of the bill to cover about 1.6 million immigrants without legal status — roughly $8.4 billion of the $9.5 billion, Department of Finance program budget manager Guadalupe Manriquez said during a recent Assembly Budget Committee hearing.

What Could Get Cut?

President Donald Trump in March said that he would not “touch Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid” but focus on getting the “fraud out of there.” However, health experts say Medicaid services would be gutted if Congress follows through on massive spending reductions to pay to extend Trump’s tax cuts.

Congressional Republicans have discussed implementing work requirements for nondisabled adults, which could affect at least 1 million Medicaid enrollees in California, the most of any state, according to an analysis by the Urban Institute.

Lawmakers also could roll back the Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, which passed in 2010 and allowed more people to qualify for Medicaid based on income. California, 39 other states, and Washington, D.C., have chosen to adopt “Medicaid expansion,” in which the federal government pays for 90% of coverage for those enrollees.

Such a move would cost California billions each year if it opted to continue coverage for the roughly 5 million additional enrollees who have gained coverage under the expansion.

Republicans could also make it tougher for states such as California to continue to draw federal aid through provider taxes such as the MCO tax, something the first Trump administration proposed but later dropped. The tax on managed care plans brings in about $5 billion a year and was endorsed by voters in a ballot initiative last fall, but the federal government has been complaining for years about how states levy such taxes on insurance plans and hospitals. If it restricts how states collect these taxes, it would likely cause a funding gap in California.

If federal cuts occur, Newsom officials acknowledge, the state couldn’t absorb the cost of existing programs. Republicans are pressuring Democrats who control the legislature to end Medi-Cal coverage of residents without legal status — something neither Newsom nor Democratic legislative leaders have expressed a willingness to do.

State leaders also could be faced with cutting optional benefits such as dental care and optometry, trimming services aimed at enhancing recipients’ quality of life, or reducing payments to managed care plans that cover 94% of Medi-Cal recipients.

That’s what California lawmakers did during the Great Recession, cutting reimbursement rates to providers and eliminating benefits including eye and dental care for adults. The governor at the time, Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger, went a step further, chopping $61 million from counties’ Medi-Cal funding in a budget bloodletting that he said contained “the good, the bad, and the ugly.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Quebec declares end to measles outbreak after no cases reported for 32 days

Health officials say an outbreak can be considered over if 32 days pass without a new reported infection.

MeaslesHealth officials say an outbreak can be considered over if 32 days pass without a new reported infection.

The Ranks of Obamacare ‘Fixers’ Axed in Trump’s Reduction of Health Agency Workforce

They’re the fixers, the ones who step in when Affordable Care Act enrollees have a problem with their coverage, like a newborn incorrectly left off a policy or discovering that a rogue broker had signed them up or switched their plan without consent. Specially trained […]

Health CareThey’re the fixers, the ones who step in when Affordable Care Act enrollees have a problem with their coverage, like a newborn incorrectly left off a policy or discovering that a rogue broker had signed them up or switched their plan without consent.

Specially trained caseworkers help resolve such issues, which might otherwise cause consumers to rack up large doctors’ bills or prevent them or their family members from getting care. Now, though, the broad federal reduction in force set in motion by the Trump administration has cut the ranks of those caseworkers, slashing two out of six divisions of caseworkers, according to one affected worker and a former Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services official familiar with the situation, Jeffrey Grant.

Currently, the number of ACA enrollees is at an all-time high of 24 million. The ACA — known as Obamacare — has long drawn disfavor from Republicans and Trump himself. The health law faces additional changes next year that, if adopted, could sow confusion and more problems. Consumers would face a new learning curve with extra paperwork and rules. And the caseworker cuts might extend the time needed to resolve any difficulties.

“It impacts not only our jobs, but all these people we serve,” said one New York City-based caseworker, who was let go in a Feb. 14 purge affecting federal employees in their probationary periods. “Usually, we would have on average 14 days to take care of a case that was very difficult, although the urgent cases would be solved within two to three business days. It will now be delayed so much more. Whole teams got wiped out completely.”

NPR and KFF Health News are not naming the two affected workers in this article because they fear professional or personal repercussions for speaking to the media.

The two teams of caseworkers were dismantled in a haphazard fashion that left some workers without an official notice but locked out of their computers.

The cuts have demoralized caseworkers, whose jobs demand a grasp of complex and arcane health insurance rules in a little-known government department that most consumers don’t interact with — CMS’ Exchange Customer Solutions Group — until they need help.

“The loss in staffing is going to reduce the ability for people to get through” to caseworkers after contacting the marketplace or other organizations for help, said Jackie Kiger, executive director of Pisgah Legal Services, a nonprofit that provides legal and ACA help for North Carolina consumers and is facing a budget reduction under a separate effort by the Trump administration to cut “navigator” funding by 90%. Navigators are government-funded nonprofits that help people enroll in the ACA or resolve problems with coverage.

The federal force reduction aims to decrease the number of employees at agencies within the Department of Health and Human Services from 82,000 to 62,000, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, the National Institutes of Health, and CMS.

CMS, which oversees the ACA and other government health programs, will lose about 300 workers, including about 30 caseworkers scattered nationwide. The cuts come amid thousands of other federal job losses, including front-line workers across an array of agencies, from Social Security field offices to the National Park Service.

In a press release, HHS estimated its reduction in force will save taxpayers $1.8 billion a year. No one from CMS responded to KFF Health News’ questions about the caseworker reductions.

What Will Be Affected?

When consumers have a problem with their ACA plan, their first step is usually to call the federal or state marketplace on which they purchased coverage.

Those call centers can handle basic questions about plans purchased on the federal exchange, which serves 31 states. (State marketplaces handle their own complex cases and don’t rely on federal caseworkers.)

When someone calls the federal marketplace 800 number with coverage problems, the inquiry probably winds up on a caseworker’s desk, said one affected caseworker. That employee received a reduction-in-force notice several days after losing access to their work computer on April 1.

Caseworkers usually don’t speak directly with consumers, the worker said. Using information sent over by the federal marketplace — including notes taken when consumers called in with problems, as well as ACA applications — they handle or oversee consumer requests, such as canceling a plan or adding a member.

One of the last problems handled by that caseworker involved a child born in November who was not added correctly to the family’s plan for 2024, meaning any care the child received during the last two months of the year was not covered and the family risked being stuck with the bills.

“This person did everything right, including calling the marketplace within 60 days to report the birth and add the newborn to their coverage,” said the worker, who was quickly able to resolve it because it was a marketplace error.

The worker, who is now soured on federal employment and will look for a new job in the private sector, said caseworkers handled an average of 30 issues a day, but that in recent months the number kept climbing, heading past 45, and grew even more intense after the Feb. 14 dismissal of probationary employees.

“It’s not an easy job,” the worker said, noting the challenge of constantly evolving rules and policies governing health plans.

Ferreting Out Fraud

In the past year, caseworkers have dealt with cases involving unauthorized enrollments or switching, a problem that ticked up in late 2023, according to KFF Health News investigations, and continued through much of last year, resulting in at least 274,000 complaints to CMS through August. The complaints centered on practices by rogue brokers who enrolled or switched coverage for consumers without their express knowledge. That could leave them without access to their health provider networks or drug coverage, or even facing a tax bill.

Though it is unclear how many such complaints fell to a federal caseworker, some improperly switched consumers want to be restored into plans they had originally chosen, while others want them canceled.

“I have seen people who were enrolled and every two or three months a broker would switch them to a different plan,” said the caseworker who was locked out in early April. “The more health plans they were enrolled in, the more difficult it was to handle on the back end.”

New hires spend months learning the ropes.

The New York-based worker let go in February during her probationary period said she had joined CMS in October and spent three months in training. Just about a month after completing that training, she was let go — a bitter irony, she said, because she had sought stability in a job with the federal government, having experienced a layoff during her private-sector career.

“I took a huge pay cut — over $40,000 — when I went from the private sector into the government,” said the mother of three whose husband serves in the military. Her federal salary was about $76,000, which is not high for an expensive market like the New York metropolitan area. “But I took it as an opportunity to get in the door and move up. Then, boom, I get hit with another layoff.”

“I can only imagine how hard it is for people with 10 to 15 years with the government who are banking on it for retirement,” she said.

Starting next year, the Trump administration has proposed several changes to the ACA, including ending year-round eligibility for very low-income applicants, requiring additional financial and eligibility documentation, and charging some people a monthly $5 fee when auto-reenrolled in coverage until they confirm their eligibility.

Such changes will “make things harder, so there you will have more things that go wrong,” said Grant, the former CMS official, who founded Schedule F Healthcare Strategies after leaving CMS. “You will then also have fewer caseworkers to handle the work.”

We’d like to speak with current and former personnel from the Department of Health and Human Services or its component agencies who believe the public should understand the impact of what’s happening within the federal health bureaucracy. Please message KFF Health News on Signal at (415) 519-8778 or get in touch here.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).