Seeking Spending Cuts, GOP Lawmakers Target a Tax Hospitals Love To Pay

On the eastern plains of Colorado, in a county of less than 6,000 people, Lincoln Health runs the only hospital within a 75-minute drive. The facility struggles financially, given its small size and the area’s tiny population. But for over a decade, the Hugo, Colorado-based […]

Health Care

If measles keeps spreading, Canada may lose 30-year elimination status: PHAC

Measles is one of the most contagious infectious diseases — more contagious than diseases like COVID-19, influenza and chickenpox.

Measles

Ontario health minister defends province’s approach amid worsening measles outbreak

Health Minister Sylvia Jones is defending the province’s record against measles as new infections rise sharply.

Measles

Montana Lawmakers Approve $124M To Revamp Behavioral Health System

HELENA, Mont. — Montana’s frayed behavioral health care system, still recovering from the effects of past budget cuts, will get a shot in the arm after state lawmakers approved sweeping changes to upgrade and expand facilities, increase community services, and revise commitment procedures. Lawmakers backed […]

Rural HealthHELENA, Mont. — Montana’s frayed behavioral health care system, still recovering from the effects of past budget cuts, will get a shot in the arm after state lawmakers approved sweeping changes to upgrade and expand facilities, increase community services, and revise commitment procedures.

Lawmakers backed the bulk of Republican Gov. Greg Gianforte’s multimillion-dollar vision to bolster and expand the system, which has experienced waitlists for care and has been working in recent years to reverse the loss of community-based mental health services and regain federal certification of the state psychiatric hospital, lost in 2022 after a spate of patient deaths. Legislators then went several steps further to fill what they saw as gaps in the governor’s proposals.

They agreed to build a new mental health facility in eastern Montana, add more beds at existing state facilities, fund more crisis beds in communities, revise some civil and criminal commitment procedures, and reimburse counties when criminal defendants ordered to state facilities are held in county jails.

“For our families that struggle in these systems, it gives us so much hope,” said Matt Kuntz, executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness’ Montana chapter, about the legislative action.

The state’s behavioral health system faced an array of problems going into the 2025 legislative session. They included shortages in community services, particularly in rural areas, created by deep cuts made in 2017 in response to a state budget shortfall, along with a backlog of criminal defendants waiting for evaluations and services at the state-run psychiatric hospital.

The prospects of the situation improving seemed dim for a long time, Kuntz said. “Then you have the governor’s office, the legislature, the counties, the county attorneys all working together to bring tangible solutions. And they got the votes,” he said.

That support built over time as the state spent money on improvements needed to regain the Montana State Hospital’s federal certification and counties came under increasing pressure due to a lack of services and treatment beds. The legislature and governor committed to review the system in 2023.

In all, lawmakers approved about $124 million in state spending and up to $40 million in federal funds over the next two years for behavioral health services, a new state-owned facility, and additional beds in existing facilities.

“The people that need our support, the people that can’t take care of themselves, the families that are struggling with their family member that can’t take care of themselves at some points in time are going to benefit from what we did,” Republican state Sen. John Esp said in summing up the legislature’s work.

The spending approved by the legislature goes well beyond the money Gianforte requested for behavioral health changes. He included 10 funding requests in his proposed state budget for the next two years that totaled about $43.5 million in state funds and $42 million in federal funds. The requests were based on recommendations from the Behavioral Health System for Future Generations Commission.

Lawmakers created that commission in 2023 to review state-funded services for people with mental illness, substance use disorders, and developmental disabilities. Legislators that year set aside $300 million to be spent in future years on recommendations made by the commission.

Even before the start of the session, some legislators questioned whether the governor’s budget did enough to address the lack of both community-based crisis services and forensic beds at the Montana State Hospital, which are for people in the criminal justice system.

Two bills introduced in January — House Bill 236 and HB 237 — sought to address lengthy jail holds experienced by some people waiting for mental health evaluations or treatment before their trials can proceed. Defendants generally obtain those services at the Montana State Hospital’s forensic unit.

Both bills failed. But testimony on the measures, as well as on the governor’s budget requests, drew attention to the backlog of people waiting in jails across the state. Legislators heard of prolonged delays — some stretching more than a year — that sometimes led to cases being dismissed because of concerns that the delays had violated the defendants’ constitutional right to a speedy trial.

By April, the legislature was considering possible fixes on several fronts. Some resulted from long hours of discussion among the parties involved.

During an April 15 hearing on Senate Bill 429 to revise criminal commitment procedures, Chad Parker, a state health department attorney, described the measure as “a very robustly negotiated bill.” Nanette Gilbertson, representing the Montana County Attorneys’ Association and the Montana Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association, said it contained elements “that I know were tough pills to swallow for both the associations I work for and the department.”

The bill would allow involuntary medication of defendants in county jails under certain circumstances — an idea state officials initially opposed — and prohibit the filing of a contempt charge if someone isn’t admitted to the Montana State Hospital for treatment because a bed isn’t available, which was important to the state to include.

Gilbertson told the House Judiciary Committee the bill was just one of several that, “taken in a package, are going to create immense change in the mental health and behavioral health system in the state of Montana.”

They include bills to reimburse counties for the costs of holding people waiting for state mental health services, allow short-term mental health holds in the community, improve delivery and payment for community services, and create more beds in state facilities for people committed through both criminal and civil procedures.

Legislators also approved money for a new mental health facility, expected to be built in eastern Montana, that will include more forensic beds.

Gianforte spokesperson Kaitlin Price said Gianforte would carefully consider the bills passed in addition to his proposals.

The governor’s original budget request focused primarily on community services. Legislators approved all but one, which would have created an electronic bed registry. The approved requests will revise reimbursement rates for developmental disability services, residential youth psychiatric treatment, and crisis and outpatient behavioral health services. They also will reopen clinics for early diagnosis of developmental disabilities in children, provide workforce incentives, and seek to improve delivery of services to people with developmental disabilities who have complex needs.

Esp, who served on the behavioral health commission and sponsored several of the bills, cautioned that the success of this year’s efforts will depend on whether future legislatures and governors spend the money needed to continue the new services.

“The problem we’ve always had around here is we look at things in two-year increments and towards the next election instead of looking at what’s the best policy for the state of Montana, long term,” he said.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Government Watchdog Expects Medicaid Work Requirement Analysis by Fall

The country’s top nonpartisan government watchdog has confirmed it is examining the costs of running the nation’s only active Medicaid work requirement program, as Republican state and federal lawmakers consider similar requirements. The U.S. Government Accountability Office told KFF Health News that its analysis of […]

Health CareThe country’s top nonpartisan government watchdog has confirmed it is examining the costs of running the nation’s only active Medicaid work requirement program, as Republican state and federal lawmakers consider similar requirements.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office told KFF Health News that its analysis of the Georgia Pathways to Coverage program could be released this fall.

In its first 100 days, the Trump administration has said rooting out waste in federal programs was a priority, allowing billionaire Elon Musk and the newly created Department of Government Efficiency broad latitude to fundamentally alter the operations of federal agencies.

The idea of a nationwide mandate that requires Medicaid enrollees to either work, study, or complete other qualifying activities to maintain coverage is gaining traction as congressional Republicans weigh proposals to cut $880 billion from the federal deficit over 10 years. The savings are intended to offset the costs of President Donald Trump’s priorities, including border security and tax cuts that would largely benefit the wealthy.

A majority of the public — regardless of political leaning — oppose funding cuts to Medicaid, according to polling released May 1 by KFF, a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

The GAO investigation comes at a critical time, said Leo Cuello, a research professor at Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families.

“Congress seems to be pursuing cuts in Medicaid in a frenetic and rushed manner,” he said. The GAO report could outline for Congress the full extent of problems with work requirements “before they rush forward and do this without thinking.”

The experiences of Georgia and Arkansas — the only two states to have run such programs — show that work requirements depress Medicaid enrollment while adding costly layers of bureaucracy.

Now, more states are trying to get signoff from the Trump administration to approve work requirements for Medicaid, the state-federal program that offers health coverage to millions of Americans with low-incomes and disabilities.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which approves Medicaid pilot programs such as work requirements, did not respond to a request for comment by publication.

The GAO found in 2019 that work requirement programs can be expensive for states to run — hundreds of millions of dollars, in some cases — and that federal officials failed to consider those costs when approving the programs, which cannot increase Medicaid spending.

Still, the Trump administration has supported work requirements. The programs require state employees to manually verify whether enrollees meet eligibility requirements and monitor their continued compliance.

In 2023, more than 90% of U.S. adults eligible for Medicaid expansion were already working or could be exempt from requirements, according to KFF.

During his confirmation hearing to lead CMS, Mehmet Oz said he was in favor of work requirements but didn’t think they should be used as “an obstacle, a disingenuous effort to block people from getting on Medicaid.”

The first Trump administration approved work requirements in 13 states. Nearly all the programs were blocked by the Biden administration or federal courts.

Georgia is one of 10 states that hasn’t fully expanded Medicaid to nearly all low-income adults.

The state launched Pathways to Coverage on July 1, 2023. It’s been a main policy priority of Republican Gov. Brian Kemp, whose office engaged in a lengthy court fight with the Biden administration after it tried to block the program.

The program cost more than $57 million in state and federal dollars through the end of 2024, with much of that going toward its administration. As of April 25, 7,410 people were enrolled, a small percentage of those who would be covered by a full Medicaid expansion. Pathways has also slowed processing times for other benefit programs in the state.

When asked about the costs and benefits of Pathways, Kemp spokesperson Garrison Douglas instead pointed to Georgia’s recently launched state-based Obamacare exchange. It saw record enrollment due, in part, to enhanced subsidies passed by the Biden administration.

“We are covering more Georgians than traditional Medicaid expansion would have, and for less money,” said Douglas, referring to the state, not federal, share of spending.

The enhanced subsidies that boosted enrollment are set to expire this year. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that extending them would cost the federal government about $335 billion over 10 years.

In March, Arkansas asked the Trump administration to relaunch its Medicaid work requirement program. The federal public comment period on the program runs through May 10. A previous version was halted by a court order in 2019, but not before more than 18,000 lost coverage in less than a year.

Georgia plans to request that the White House renew its program with modest changes, including reducing how frequently enrollees must prove to the state they’re working or engaging in other qualifying activities.

The GAO investigation into Georgia’s work requirement program comes after three Democratic U.S. senators — Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock of Georgia and Ron Wyden of Oregon — asked the GAO in December for an investigation into the program’s costs. Their request cited reporting by KFF Health News.

“I pushed for this GAO report because I am confident its findings will further support what we already know: Pathways to Coverage costs the taxpayers more money and covers fewer people than had the state simply joined 40 other states in closing the health care coverage gap,” Warnock said in a statement.

The GAO said it aims to figure out how much Georgia has spent to run the program, how much of that was federal money, and how that spending is being tracked.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Covered California Pushes for Better Health Care as Federal Spending Cuts Loom

Faced with potential federal spending cuts that threaten health coverage and falling childhood vaccination rates, Monica Soni, the chief medical officer of Covered California, has a lot on her plate — and on her mind. California’s Affordable Care Act health insurance exchange covers nearly 2 […]

Health CareFaced with potential federal spending cuts that threaten health coverage and falling childhood vaccination rates, Monica Soni, the chief medical officer of Covered California, has a lot on her plate — and on her mind.

California’s Affordable Care Act health insurance exchange covers nearly 2 million residents and 89% of them receive federal subsidies that reduce their premiums. Many middle-income households got subsidies for the first time after Congress expanded them in 2021, which helped generate a boom in enrollment in ACA exchanges nationwide.

From the original and enhanced subsidies, Covered California enrollees currently get $563 a month on average, lowering the average monthly out-of-pocket premium from $698 to $135, according to data from Covered California.

The 2021 subsidies are set to expire at the end of this year unless Congress renews them. If they lapse, enrollees would be on the hook to pay an average of $101 a month more for health insurance — not counting any premium hikes in 2026 and beyond. And those middle-income earners who did not qualify for subsidies before would lose all financial assistance — $384 a month, on average — which Soni fears could prompt them to drop out.

At the same time, vaccination rates for children 2 and under declined among 7 of the 10 Covered California health plans subject to its new quality-of-care requirements. Soni, a Los Angeles native who came to Covered California in May 2023, oversees that program, in which health plans must meet performance targets on blood pressure control, diabetes management, colorectal cancer screening, and childhood vaccinations — or pay a financial penalty.

Lack of access to such key aspects of care disproportionately affects underserved communities, making Covered California’s effort one of health equity as well. Soni, a Harvard-trained primary care doctor who sees patients one day a week at an urgent care clinic in Los Angeles County’s public safety net health system, is familiar with the challenges those communities face.

Covered California reported last November that its health plans improved on three of the four measures in the first year of the program. But childhood immunizations for those under 2 declined by 4%. The decline is in line with a national trend, which Soni attributed to postpandemic mistrust of vaccines and “more skepticism of the entire medical industry.”

Most parents have heard at least one untrue statement about measles or the vaccine for it, and many don’t know what to believe, according to an April KFF poll.

Health plans improved on the other three measures, but not enough to avoid penalties, which yielded $15 million. The exchange is using that money to fund another effort Soni manages, which helps 6,900 Covered California households buy groceries and contributes to over 250 savings accounts for children who get routine checkups and vaccines. Some of the penalty money will also be used to support primary care practices around California.

In addition to her bifurcated professional duties, Soni is the mother of two young children, ages 4 and 7. KFF Health News senior correspondent Bernard J. Wolfson spoke with Soni about the impact of possible federal cuts and the exchange’s initiative to improve care for its enrollees. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Covered California has record enrollment of nearly 2 million, boosted by the expanded federal subsidies passed under the Biden administration, which end after this year. What if Congress does not renew them?

A: Our estimates are that it will approach 400,000 Californians who would drop coverage immediately. We hear every day from our folks that they’re really living on the margins. Until they got some of those subsidies, they could not afford coverage.

As a primary care doctor, I am the one to treat folks who show up with preventable cancers because they were too afraid to think about what their out-of-pocket costs would be. I don’t want to go back to those days.

Q: Congress is considering billions in cuts to Medicaid. How would that affect Covered California and the state’s population more broadly, given that more than 1 in 3 Californians are on Medi-Cal, the state’s version of Medicaid?

A: Those are our neighbors, our friends. Those are the people working in the restaurants we eat at. Earlier cancer screenings, better chronic disease control, lower maternal mortality, more substance use disorder treatment: We know that Medicaid saves lives. We know it helps people live longer and better. As a physician, I would be hard-pressed to argue for rolling back anything that saves lives. It would be very distressing to watch that come to California.

Q: Why did Covered California undertake the Quality Transformation Initiative?

A: We were incredibly successful at covering nearly 2 million, but frankly we didn’t see improvements in quality, and we continue to see gaps for certain populations in terms of outcomes. So, I think the question became much more imperative: Are we getting our money’s worth out of this coverage? Are we making sure people are living longer and better, and if not, how do we up the ante to make sure they are?

Q: There’s a penalty for not meeting the targets, but no bonuses for meeting them: You meet the goals or else, right?

A: We don’t say it like that, but that is true. And we didn’t make it complicated. It’s only four measures. It’s things that as a primary care doctor I know are important, that I take care of when I see people in my practice. We said get to the 66th percentile on these four measures, and there’s no dollars that you have to pay. If you don’t, then we collect those funds.

Q: And you use the penalty money to fund the grocery assistance and child savings accounts.

A: That’s exactly right. We had this opportunity to think about what would we use these dollars for and how we actually make a difference in people’s lives. So, we cold-called hundreds of people, we sent surveys out to thousands of folks, and what we heard overwhelmingly was how expensive it is to live in California; that folks are making trade-offs between food and transportation, between child care and food — just impossible decisions.

Q: You will put up to $1,000 a child into those savings accounts, right?

A: That’s right. It’s tied to doing those healthy behaviors, going to child well visits and getting recommended vaccines. We looked at the literature, and once you get to even just $500 in an account, the likelihood of a kid going to a two- or four-year school increases significantly. It’s actually because they’re hopeful about their future, and it changes their path of upward mobility, which we know changes their health outcome.

Q: Given the rise in vaccine skepticism, are you worried that the recent measles outbreak could grow?

A: I am very concerned about it. I was actually reading some posts from a physician colleague who trained decades earlier and was talking about all the diseases that my generation of physicians have never seen. We don’t actually know how to diagnose and take care of a number of infectious diseases because they mostly have been eradicated or outbreaks have been really contained. So, I feel worried. I’ve been brushing off my old textbooks.

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

‘Sharp rise’ in Ontario measles cases with 223 new infections

Public Health Ontario is reporting 223 new measles cases since last week as the spread in its southwestern region grows.

MeaslesPublic Health Ontario is reporting 223 new measles cases since last week as the spread in its southwestern region grows.

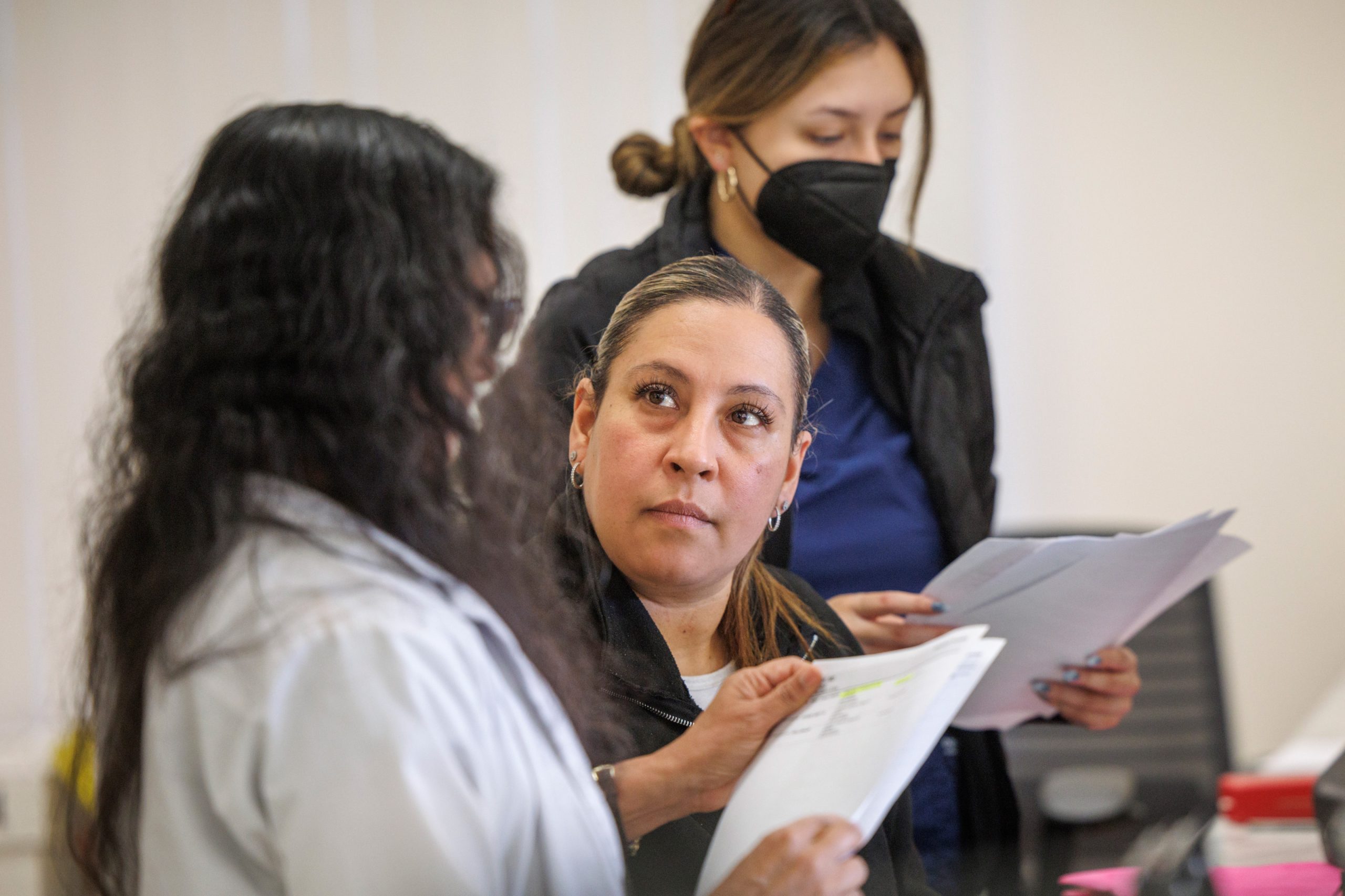

California’s Primary Care Shortage Persists Despite Ambitious Moves To Close Gap

Sumana Reddy, a primary care physician, struggles on thin financial margins to run Acacia Family Medical Group, the small independent practice she founded 27 years ago in Salinas, a predominantly Latino city in an agricultural valley often called “the salad bowl of the world.” Reddy […]

Rural HealthSumana Reddy, a primary care physician, struggles on thin financial margins to run Acacia Family Medical Group, the small independent practice she founded 27 years ago in Salinas, a predominantly Latino city in an agricultural valley often called “the salad bowl of the world.”

Reddy can’t match the salaries offered by larger health systems — a difficulty compounded by a widespread shortage of primary care doctors.

The shortage is tied largely to the lower pay and relative lack of prestige associated with primary care, making recruitment difficult. “It certainly is challenging to expose medical students early in their careers to the joys of this kind of integrated health care,” Reddy said. “The relationships we build and the care we provide truly allow people to live longer with a better quality of life.”

Hoping to increase revenue so Acacia can afford to pay more, Reddy has signed the practice up for alternative payment methods with health plans that offer bonuses for meeting certain primary care goals tied to child vaccinations, blood pressure control, and screenings for breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and mental health. Such pay-for-performance arrangements are among the many efforts by industry players and state officials to confront the problems plaguing primary care.

Medical students frequently opt not to go into primary care, and that’s not good for patients. People with regular primary care providers are more likely to get preventive care that avoids serious illnesses and feel more empowered to advocate for themselves. They’re also less likely to encounter language barriers, resort to costly emergency room visits, or forgo care.

Six years after the influential California Future Health Workforce Commission made a series of recommendations to plug a projected shortage of 4,100 primary care providers in 2030, a number of public and private initiatives have proliferated around the state to address the problem. They include new residency slots, debt forgiveness, waived medical school tuition, new ways of paying doctors, expanded nurse practitioner roles, and a statewide target to increase primary care spending. Hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars have been allocated for some of these efforts.

But numerous academic experts and medical professionals believe those moves, while well intended, have been scattershot and insufficient. “The pieces are there,” said Monica Soni, chief medical officer of Covered California, the state’s Affordable Care Act health insurance marketplace. “I am worried we started a little too late, and I think it’s a little too siloed.”

A study published in 2022 by the California Health Care Foundation found that substantial progress had been made on some of those goals, including recruitment of students from low-income households and communities of color. A separate analysis from the foundation showed that, from 2020 to 2023, California jumped about 10 spots in a ranking of states by primary care residents and fellows per capita.

However, the latest state data shows nearly 15 million Californians live in areas without enough primary care providers to meet patient needs.

State budget constraints and potential federal spending cuts, especially to Medicaid, could exacerbate shortages in areas already desperate for clinicians and dampen hopes of building a robust primary care system that state officials and virtually everyone in the industry agree would be a strong defense against serious — and costly — illnesses. Federal cuts could also hit medical training and hospital systems.

“Many of us are very scared about threats from both the Trump administration and Republicans in Congress,” said Kevin Grumbach, a family community medicine professor at the University of California-San Francisco.

Acute Primary Care Shortages

California’s lack of primary care providers, including doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants, is most acute in rural parts of the state, particularly in the north and the Central Valley. Entire rural counties, including Del Norte, Madera, Tulare, and Yuba, are designated shortage areas, according to state data. Some densely populated urban areas, including parts of Los Angeles, also confront shortages.

Many Californians face months-long waits for appointments or have to travel long distances or go to emergency rooms for nonurgent medical needs, which means hours spent in crowded waiting rooms for unnecessarily expensive care.

In Chico, 90 miles north of Sacramento, the emergency room at the only hospital in town has seen a sharp increase in patients over the past decade, due in part to a lack of primary care providers in the area.

“People who don’t have a primary care provider — which is a lot, because there are not enough — end up in the ER when they need routine care,” said David Alonso, a local internal medicine doctor. “The ER then says, ‘OK, you should follow up with your primary care provider,’ and they’re like, ‘We don’t have one.’”

Yalda Jabbarpour, director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies, a health policy think tank, said failure to invest robustly in primary care has robbed the public of its benefits.

The field has historically been underfunded, accounting for less than 5% of national health care spending in 2022, according to the Milbank Memorial Fund, a national nonprofit focused on population health and health equity.

The consequences are clear.

The U.S. spends significantly more per capita on health care than other industrialized nations, and yet Americans aren’t any healthier. Chronic conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, arthritis, and Alzheimer’s, as well as mental illness, account for 90% of the $4.5 trillion spent on health care every year.

Medical students, often faced with staggering educational debt, are increasingly choosing higher-paid specialties over primary care. The average salary of a family medicine physician is slightly over $300,000, compared with more than $565,000 for a cardiologist and over $763,000 for a neurosurgeon, according to one study.

“If you are going to pay over $300,000 to go to medical school, you want to be a neurosurgeon; you don’t want to be a family practice doctor,” said William Barcellona, executive vice president of government affairs at America’s Physician Groups, a Los Angeles-based professional association representing 360 medical groups and independent practice associations nationwide.

Barcellona said the Golden State’s high housing costs also make recruiting difficult.

But it’s not only pay that tempers enthusiasm for primary care. It’s also burnout from so many unpaid hours spent recording details of medical visits in electronic health records; haggling with insurance companies for treatment authorization; answering phone calls and emails from patients; or searching far and wide — often in a health care desert — for specialists with the right expertise.

Debby Lee, the daughter of Hmong immigrants from Laos, experienced this kind of frustration firsthand.

Cultural and linguistic barriers faced by her family motivated her to pursue internal medicine. Lee worked part of her residency at a community clinic serving Hmong in the Sacramento area. She loved the patients, as well as her co-workers. But she was burdened by outdated technology that limited the number of patients she could see. “I just saw myself kind of burning out being in that setting,” Lee said.

When the clinic invited her to stay, she declined, taking a job with a bigger health system.

Solutions to the Shortage

Besides residencies, other efforts support primary care.

The Health Plan of San Mateo offers grants to help medical practices retain and add to primary care staff. In exchange, the practices — some single physicians serving patients in California’s Medicaid program, Medi-Cal — must show they have increased their patient load and retained newly hired providers for five years.

The idea is to provide capital so doctors can hire the staff they need to run their practices efficiently, increase salaries, offer bonuses, and even take sabbaticals. Such efforts are consistent with one of the main thrusts of the 2019 workforce report: to increase investment in primary care.

California recently joined several other states, including Connecticut, Oklahoma, and Rhode Island, in setting a target to increase primary care spending. So far, those policies have yielded mixed results.

Late last year, California’s Office of Health Care Affordability set a target to make primary care account for 15% of total health care spending by 2034, more than double the current proportion. It imposes no requirements, relying on the goodwill of health plans to work with medical providers.

Greater spending on primary care would mean better pay and more people working in the field, said Richard Kronick, a public health professor at UC-San Diego and a member of the OHCA board. “That’s a big change. Will it happen? I don’t think anyone can predict the future with any certainty.”

Stephen Shortell, a professor emeritus of health policy and management at UC-Berkeley, said “some of that increase might occur, but at some point, it might need to be made mandatory.”

In its report, the workforce commission also cited the importance of alternative forms of primary care payment that offer extra cash for quality care. The affordability office has set targets to encourage such payment methods. The aim is to transform the system from one in which every medical service has a price tag to one that treats people holistically, and in which adherence to medical standards brings more money to doctors and their office staff.

Such arrangements are common among HMOs, though less so in primary care practices. Where they do exist, different health plans and other payers generally design them differently, which means primary care practices manage multiple payment models, adding to their administrative burden.

Reddy’s family practice is participating in a one-year demonstration project launched in January intended to reduce that burden by having multiple insurers work together in one payment plan.

The project brings together three large insurers — Health Net, Aetna, and Blue Shield of California — and 10 independent practices across the state with the goal of improving care while boosting revenue for the medical groups. It is administered by two industry groups, the Integrated Healthcare Association and the California Quality Collaborative.

On top of customary payments, either for services rendered or monthly per-member allotments, the medical practices receive bonuses for meeting targets or improving their performance on core measures.

Participating practices also receive monthly per-patient payments for “population health management,” which means managing the collective health of their patients. And they can search a single platform to find all their patients covered by one of the three plans.

In addition to extra payments and fewer administrative hassles, the health plans pay for a “practice coach,” whose job is to help primary care groups meet their targets and provide more seamless care.

The idea is to add more insurers and medical groups over time, said Todd May, Health Net’s medical director for commercial health plans, who is among those driving the project. “In addition to better outcomes, we’d like to see a stronger, more robust, and more satisfied primary care workforce,” he said.

Reddy hopes she can increase Acacia’s revenue by 20%, using the extra money from this and other pay-for-performance arrangements. That, she said, would enable her to raise pay for her staff and hire clinicians.

For many years, her practice has limited the number of patients it has accepted. But after searching for the better part of five years, Reddy has hired a doctor on a half-time basis and another is coming on board in June.

“This is the most hopeful I have felt in decades,” Reddy said.

Phillip Reese contributed to this report.

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Federal Cuts Gut Food Banks as They Face Record Demand

Food bank shortages caused by high demand and cuts to federal aid programs have some residents of a small community that straddles Idaho and Nevada growing their own food to get by. For those living in Duck Valley, a reservation of about 1,000 people that […]

Health CareFood bank shortages caused by high demand and cuts to federal aid programs have some residents of a small community that straddles Idaho and Nevada growing their own food to get by.

For those living in Duck Valley, a reservation of about 1,000 people that is home to the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes, there’s just one grocery store where prices are too high for many to afford, said Brandy Bull Chief, local director of a federal food distribution program for tribes. The next-closest grocery stores are more than 100 miles away in Mountain Home, Idaho, and Elko, Nevada. And the local food bank’s troubles are mirrored by many nationwide, squeezed between growing need and shrinking aid.

Reggie Premo, a community outreach specialist at the University of Nevada-Reno Extension, grew up cattle ranching and farming alfalfa in Duck Valley. He runs workshops to teach residents to grow produce. Premo said he has seen increased interest from tribal leaders in the state worried about high costs while living in food deserts.

“We’re just trying to bring back how it used to be in the old days,” Premo said, “when families used to grow gardens.”

Food bank managers across the country say their supplies have been strained by rising demand since the covid pandemic-era emergency Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits ended two years ago and steepening food prices. Now, they say, demand is compounded by recent cuts in federal funding to food distribution programs that supply staple food items to pantries nationwide.

In March, the U.S. Department of Agriculture cut $500 million from the Emergency Food Assistance Program, which buys food from domestic producers and sends it to pantries nationwide. The program has supplied more than 20% of the distributions by Feeding America, a nonprofit that serves a network of over 200 food banks and 60,000 meal programs.

The collision between rising demand and falling support is especially problematic for rural communities, where the federal program might cover 50% or more of food supplied to those in need, said Vince Hall, chief government relations officer of Feeding America. Deepening the challenge for local food aid organizations is an additional $500 million the Trump administration slashed from the USDA Local Food Purchase Assistance Cooperative Agreement Program, which helped state, tribal, and territorial governments buy fresh food from nearby producers.

“The urgency of this crisis cannot be overstated,” Hall said, adding that the Emergency Food Assistance Program is “rural America’s hunger lifeline.”

Farmers who benefited from the USDA programs that distributed their products to food banks and schools will also be affected. Bill Green is executive director for the Southeast region of Common Market, a nonprofit that connects farmers with organizations in the Mid-Atlantic, the Southeast, Texas, and the Great Lakes. Green said his organization won’t be able to fill the gap left by the federal cuts, but he hopes some schools and other institutions will continue buying from those farmers even after the federal support dries up.

“I think that that food access challenge has only been aggravated, and I think we just found the tip of the iceberg on that,” he said.

Food Bank for the Heartland in Omaha, Nebraska, for example, is experiencing four times the demand this year than in 2018, according to Stephanie Sullivan, its assistant director of marketing and communications. The organization expects to provide food to 580,000 households across the 93 counties it serves in Nebraska and western Iowa this fiscal year, the highest number in its history, she said.

“These numbers should be a wake-up call for all of us,” Sullivan said.

The South Plains Food Bank in Texas projects it will distribute approximately 121,000 food boxes this year to people in need across the 19 counties it serves, compared with an average 90,000 annually before the pandemic. CEO Dina Jeffries said the organization now is serving about 25% more people, while shouldering the burden of decreased funding and food products.

In Nevada, the food bank that helps serve communities in the northern part of the state, including the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes of the Duck Valley Reservation, provides food to an average of 160,000 people per month. That’s a 76% increase over its clientele before the pandemic, and the need continues to rise, said Jocelyn Lantrip, director of marketing and communications for the Food Bank of Northern Nevada.

Lantrip said one of the most troubling things for the food bank is that the USDA commodities shipped for local distribution often are foods that donations don’t usually cover — things like eggs, dairy, and meat.

“That’s really valuable food to our neighbors,” she said. “Protein is very difficult to replace.”

Forty percent of people who sought assistance from food banks during the pandemic did so for the first time, Hall said. “Many of those families have come to see their neighborhood food bank not as a temporary resource for emergency help but an essential component of their monthly budget equation.”

About 47 million people lived in food-insecure households in 2023, the most recent USDA data available.

Bull Chief, who also runs a small food pantry on the Duck Valley Reservation, said workers drive to Elko to pick up food distributed by the Food Bank of Northern Nevada. But sometimes there’s not much to choose from. In March, the food pantry cut down its operation to just two weeks a month. She said sometimes they must weigh whether it’s worth spending money on gas to pick up a small amount of food.

When the food pantry opened in 2020, Bull Chief said, it helped 10 to 20 households a month. That number is 60 or more now, made up of a broad range of community members — teens fresh out of high school and living on their own, elders, and people who don’t have permanent housing or jobs. She said providing even small amounts of food can help households make ends meet between paychecks or SNAP benefit deposits.

“Whatever they need to get to survive for the month,” Bull Chief said.

Pinched food banks, elevated need, and federal cuts mean there’s very little resiliency in the system, Hall said. Additional challenges, like an economic slowdown, policy changes to SNAP or other federal nutrition programs, or natural disasters could render food banks unable to meet needs “because they are stretched to the breaking point right now.”

A proposed budget resolution passed by the U.S. House of Representatives in April would require $1.7 trillion in net funding cuts, and anti-hunger advocates fear SNAP could be a target. More people living in rural parts of the country rely on SNAP than people in urban areas because of higher poverty rates, so they would be disproportionately affected.

An extension of the federal 2018 Farm Bill, which lasts until Sept. 30, included about $450 million for the Emergency Food Assistance Program for this year. But the funding that remains doesn’t offset the cuts, Hall said. He hopes lawmakers pass a new farm bill this year with enough money to do so.

“We don’t have a food shortage,” he said. “We have a shortage of political will.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

The Patient Expected a Free Checkup. The Bill Was $1,430.

Carmen Aiken of Chicago made an appointment for an annual physical exam in July 2023, planning to get checked out and complete some blood work. The appointment was at a family medicine practice run by University of Illinois Health. Aiken said the doctor recommended they […]

Health CareCarmen Aiken of Chicago made an appointment for an annual physical exam in July 2023, planning to get checked out and complete some blood work.

The appointment was at a family medicine practice run by University of Illinois Health. Aiken said the doctor recommended they undergo a Pap smear, which they hadn’t had in more than a year, and testing for sexually transmitted infections. Aiken, who works for a nonprofit and uses the pronoun they, said they were also encouraged to get the HPV vaccine.

They’d tested positive for HPV in 2019 and eventually cleared the virus but had not received the vaccine to prevent future infections.

“Sounds like a good idea,” Aiken, 37, recalled telling the doctor.

They also needed some lab work done, part of routine monitoring for one prescription. After being examined, Aiken said, they were directed to a different part of the office building to get blood drawn and receive the first dose of the vaccine before leaving.

Then the bill came.

The Medical Procedure

Services at Aiken’s appointment included a pelvic exam, a vaccination, and blood work, checking, in part, glucose levels and liver function.

An annual physical exam typically includes a variety of services, many of which insurers are required to cover under the Affordable Care Act, such as reviewing the patient’s health history, screening for high cholesterol, or performing a Pap smear, a procedure to check the cervix for signs of cancer.

Updating immunizations is also a common, covered service at checkups. The vaccine for HPV, or the human papillomavirus, provides protection against an infection that can cause several types of cancer. Federal health officials recommend being immunized for HPV at age 11 or 12, though the vaccine also can be administered later in life.

The Final Bill

$1,430.13: $1,223.22 for lab services and pathology, plus $206.91 for “professional services,” which included a charge for a 40-minute “High Mdm” outpatient visit — indicating a high level of “medical decision-making” — as well as charges for immunization administration and vaccines.

The Billing Problem: Diagnostic Blood Work With a Hospital Price Tag

Not all services that may be provided as part of an annual physical are paid for by insurance as preventive care.

A patient who needs blood work for a specific medical concern — as Aiken did, for medication monitoring — could be required to pay part of the bill. That’s the case even if the blood work is performed during a checkup alongside preventive services. Some health insurers pay for standard blood work as part of a preventive visit, but that’s not always the case.

Aiken had purchased a health insurance plan on the federal marketplace and said they were confident the visit would be covered at no cost to them.

When they got a bill for more than $1,400, Aiken thought, “How did this happen?” They said they called their insurer, BlueCross BlueShield of Illinois, then filed an appeal for the $1,223.22 amount they owed for lab services after their initial inquiry went nowhere. “Surely this is a misunderstanding.”

But their insurer sided with UI Health’s position that the blood work rendered during the appointment was not preventive. In a letter denying Aiken’s appeal, BlueCross BlueShield of Illinois decided that “the labs were billed correctly as diagnostic.”

Under the plan’s parameters, the insurer determined Aiken remained on the hook for 50% of the cost of outpatient labs performed in a hospital setting.

Dave Van de Walle, a spokesperson for BlueCross BlueShield of Illinois, would not discuss Aiken’s bill with KFF Health News.

Francesca Sacco, a spokesperson for UI Health, said in an emailed statement that Aiken scheduled the appointment for “medication monitoring and to obtain a vaccine.”

“Medication monitoring is not considered a wellness benefit under the Affordable Care Act,” she said.

Sacco also said Aiken’s labs were sent for processing to University of Illinois Hospital, more than a mile away from the family medicine practice.

That left Aiken owing more. Hospitals typically charge much more than physicians’ offices or independent commercial labs for the same tests.

Related Articles

-

He Had Short-Term Health Insurance. His Colonoscopy Bill: $7,000.

Mar 28, 2025

-

A Runner Was Hit by a Car, Then by a Surprise Ambulance Bill

Feb 28, 2025

-

Most Insurance Covers IUDs. Hers Cost More Than $14,000.

Jan 31, 2025

The distinction between a preventive visit and a diagnostic one is important for billing purposes: It dictates who’s on the hook for the bill. A preventive visit generally comes at no cost to patients. But a visit for an ongoing medical issue is usually classified as diagnostic, leaving the patient subject to copays and deductibles — or even charged for two separate appointments.

Patients may not notice a difference in the exam room. Much of that nuance is determined by the medical provider and captured on the bill.

Confusion still persists 15 years after the ACA’s preventive services protections took effect, said Sabrina Corlette, a founder and co-director of the Center on Health Insurance Reforms at Georgetown University.

“This is an outrageous bill for what should have been routine care,” Corlette said. “People just don’t have this kind of money lying around.”

The Resolution

After the insurer denied their appeal, they “fell down a hole into despair about it for a while,” Aiken said.

“And then someone really wise was like, ‘You can pay it and then just stop thinking about it.’”

So that’s what Aiken did: “I put it on my credit card.”

UI Health’s Sacco said the hospital system is committed to working with insurers to resolve cost-sharing disputes.

“However, it is the insurance company’s sole discretion whether a service is fully covered or subject to cost sharing,” she said. “In this case, the insurer determined that cost sharing would be applicable to a specific portion of the services provided to the patient. Based on this determination, the patient was billed accordingly by UI Health.”

The experience left its mark on Aiken. Last year, they said, they walked out of an urgent-care visit after a doctor recommended a Pap smear — fearing they’d incur another large bill.

The Takeaway

Delaying or avoiding care can lead to worse outcomes, which is why lawmakers tried to ensure patients generally would pay nothing for preventive services, such as immunizations, under the ACA.

Annual checkups are a key element of preventive care. For instance, most adults who never received the HPV vaccine do not know they are still eligible, so it’s critical to inform them of their options, said Verda Hicks, a gynecologic oncologist based in Kansas City, Missouri.

The vaccine offers protection against nine types of HPV, she said. It also prevents HPV-related cancers in men, so the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends boys receive the immunization, too.

“Get vaccinated,” Hicks said. “We just do not have the same tools for many other cancers.”

Keep in mind that your coverage may vary — some insurance companies won’t cover the cost of the vaccine for some older patients — and the same services may be subject to different cost-sharing rules depending on whether they are conducted for prevention versus diagnosis.

Also, prices can vary depending on where care is delivered and tests are performed. If you need a blood test, ask that your doctor send the requisition to a commercial, in-network lab. Patients may not realize that labs drawn at a clinic may be sent to a hospital for testing, exposing them to greater costs.

There has been a push in Congress to eliminate this price variation through “site-neutral” payment policies. Regardless of location, the price for routine care would be reimbursed at the same amount.

“Site-neutral reforms could potentially have significantly reduced Carmen’s expenses,” said Christine Monahan, an assistant research professor at Georgetown’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms.

Meanwhile, a case before the Supreme Court could upend the health system by eliminating the requirement that insurers cover preventive services like vaccines and annual screenings at no cost to patients. The high court heard oral arguments April 21.

If the justices side with the plaintiffs this term, Georgetown’s Corlette said, “then we all potentially lose access to free, high-value preventive care, and that would be a real shame.”

Bill of the Month is a crowdsourced investigation by KFF Health News and The Washington Post’s Well+Being that dissects and explains medical bills. Since 2018, this series has helped many patients and readers get their medical bills reduced, and it has been cited in statehouses, at the U.S. Capitol, and at the White House. Do you have a confusing or outrageous medical bill you want to share? Tell us about it!

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

In a Broken Mental Health System, a Tiny Jail Cell Becomes an Institution of Last Resort

POLSON, Mont. — When someone accused of a crime in this small northwestern Montana town needs mental health care, chances are they’ll be locked in a basement jail cell the size of a walk-in closet. Prisoners, some held in this isolation cell for months, have […]

Rural HealthPOLSON, Mont. — When someone accused of a crime in this small northwestern Montana town needs mental health care, chances are they’ll be locked in a basement jail cell the size of a walk-in closet.

Prisoners, some held in this isolation cell for months, have scratched initials and the phrase “love hurts” into the metal door’s brown paint. Their pacing has worn a path into the cement floor. Many are held in a sort of limbo, not convicted of a crime but not stable enough to be released. They sleep on a narrow cot next to a toilet. The only view is a fluorescent-lit hallway visible through a small window in the door.

Lake County Attorney James Lapotka stood at the cell’s center talking about the people he helps confine here. He stretched out his arms, his fingertips just shy of touching opposite walls. “I’m getting anxiety just being in here,” Lapotka said.

Last year, a man sentenced for stealing a rifle stayed in that cell 129 days. He was waiting for a spot to open at Montana’s only state-run psychiatric hospital after a mental health evaluator deemed he needed care, according to court records.

A man in the next cell around the same time was on the same waitlist roughly five months. He faced near-daily stints in the jail’s emergency restraint chair — a steel contraption wrapped in foam with straps for his shoulders, arms, and legs. He regularly saw the jail’s mental health doctor. Still, Joel Shearer, a Lake County detention commander, said the man routinely experienced psychotic episodes and asked to be locked in the chair when he felt one coming on and stayed there until his screams subsided.

“Somebody who’s having a mental health crisis — they don’t belong here,” Lapotka said. “We don’t have anywhere else.”

Lake County’s two, roughly 30-square-foot isolation cells are an example of how communities nationwide are failing to provide mental health services — crisis care, in particular. Nearly half of the people locked in local jails in the U.S. have a mental illness.

More than half of Wyoming’s 23 sheriffs told lawmakers there that they were housing people in crisis awaiting mental health care for months, WyoFile reported in January. Nevada has struggled despite a $500 daily fine for each jailed patient whose treatment is delayed. Disability Rights Oregon has said delays in that state continue after two people died in jail while on the state’s psychiatric waitlist.

In Montana, counties are jailing mental health patients they’re not equipped to handle when the Montana State Hospital is at capacity. Few local hospitals have their own inpatient psychiatric beds. As a result, people arrested for anything from petty theft to felony assault can be jailed for months or longer as their mental health worsens. Many haven’t been convicted of a crime.

Montana officials have known for years they have a problem. State officials have said they don’t have space for all the people ordered to the hospital. The psychiatric hospital has 270 beds, with 54 for people in the criminal justice system. Staffing shortages can shrink that capacity further.

The Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services backed two bills this legislative session that would shield the state from liability for delays when the Montana State Hospital is full. Ahead of the bills, the agency wrote the hospital has “struggled to maintain appropriate levels of care” due to money and staffing constraints, a lack of community-based services, and having no control over the flow patients Montana courts send its way.

The agency also announced April 23 that $6.5 million was available through one-time grants to help set up jail-based mental health stabilization services.

Officials have said patients deserve care closer to home, in less restrictive settings. But counties say the local services needed don’t exist.

“You have to do the hard things first,” said Matt Kuntz, executive director of the Montana chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. “You have to build the beds.”

Health advocates have backed a proposal that would require the state to pay for community commitments. That measure is headed to Republican Gov. Greg Gianforte after passing the state House and Senate. Another bill that was still pending would create a new psychiatric hospital for people in the justice system. But implementing those ideas could take years.

The number of inpatient beds for people with a serious mental illness nationwide has plummeted. At one time, that drop was intentional, part of a movement away from locking people up in state-run mental hospitals. But the intended fix, local homelike centers, hasn’t filled the void.

One of Montana’s biggest providers, Western Montana Mental Health Center, had to close some of its crisis sites because of money problems, said Western’s CEO, Bob Lopp. That includes a facility less than a mile from the Lake County jail.

“If that’s not where the funding is, you can’t just do it for the sake of argument and hope that it comes,” Lopp said.

Gianforte has promised to pour money into rebuilding the state’s behavioral health system. Mental health workers in small towns find such promises hard to trust after seeing local services come and go for years.

Health department spokesperson Holly Matkin said the agency is proud of its work to fix “systems that have been broken for too long” and that it will improve services for people who need inpatient care in their communities.

Lake County is known to outsiders as an Instagram-worthy stop on their way to Glacier National Park. It overlaps with the Flathead Indian Reservation, land of the Bitterroot Salish, Upper Pend d’Oreille, and Kootenai tribes. It’s home to a slice of the Rocky Mountains and a gateway to millions of acres of wilderness. Polson, the county seat and site of the jail, is a town of 5,600 on the southern shore of Flathead Lake, one of the largest lakes west of the Mississippi River.

Vincent River has worked as the jail’s sole mental health clinician for 25 years. He said he’s not always available because he’s the only psychologist in four northwestern Montana counties evaluating whether a person in jail needs psychiatric care.

Some are released without care if they linger too long on the state hospital’s waitlist.

“I talk to these family members. I hear them plead with me with their fear in their voices and tell me all that’s been going on for days or weeks or months,” River said. “And then I can’t get people into the hospital. That is a giant crisis.”

It’s not just the state hospital. River said he can’t get people into any psychiatric bed in Montana because there are too few. Instead, he tries to stabilize people while they’re jailed. That has shortfalls.

The jail can’t force someone in psychosis to take medication without a court order and a qualified doctor on hand to administer the prescription. Lake County’s aging facility has faced lawsuits because of poor conditions amid overcrowding, and River has to see patients wherever there’s room.

There isn’t even space for the jail’s restraint chair. Jail workers leave strapped-down prisoners in a hallway or locker room.

River said many gradually get better and leave isolation. Some don’t.

“They languish there, psychotic and lonely,” he said, “at the mercy of what the voices are telling them.”

Locals are working to fill some gaps. A mobile team launched in February is staffed by people who have lived with mental and substance use disorders to provide peer support. But someone truly in crisis has only two options: jail or an emergency room.

The room reserved for people in crisis at Providence St. Joseph Medical Center in Polson leaves patients both isolated and without privacy. The locked door’s thick glass looks onto a busy emergency room hallway.

Those who deteriorate enough to be deemed dangerous to themselves or others are sent down the road to jail.

Rebecca Bontadelli, an ER physician, said patients can be housed in the room for days as hospital staffers scour Montana and nearby states for an open psychiatric bed. Some reject care in the meantime.

“We’re not really helping them,” Bontadelli said. “They feel like they’re in prison.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Trump Administration Retreats From 100% Withholding on Social Security Clawbacks

The Social Security Administration is backing off a plan it announced in March to withhold 100% of many beneficiaries’ monthly payments to claw back money the government had allegedly overpaid them. Instead, the agency will default to withholding 50% of old-age, survivors, and disability insurance […]

Health CareThe Social Security Administration is backing off a plan it announced in March to withhold 100% of many beneficiaries’ monthly payments to claw back money the government had allegedly overpaid them.

Instead, the agency will default to withholding 50% of old-age, survivors, and disability insurance benefits, the agency said in an “emergency message” to staff dated April 25.

The agency long made it a routine to halt benefits to recoup billions of dollars it sent recipients but later said they should not have received. A policy under the Joe Biden administration to provide relief to beneficiaries, who often live on the fringe of poverty, last year had capped the clawbacks at 10%.

The partial reversal is another twist in the Trump administration’s tumultuous approach to Social Security, which has included staff cuts and the acting commissioner’s threat, which has since been withdrawn, to essentially shut down the agency.

The emergency message involves the agency’s practice of paying beneficiaries money they were not supposed to receive — and then, often after years have passed and the amounts have ballooned to tens of thousands of dollars or more per person — demanding the money back, even if the overpayment was Social Security’s fault.

In many cases, recovering the money had entailed withholding 100% of monthly benefits.

Millions of beneficiaries, including people struggling to get by on monthly checks, have received overpayment notices, a 2023 investigation by KFF Health News and Cox Media Group found. Clawbacks have left some homeless, the news organizations reported.

In the aftermath of that reporting, Martin O’Malley, tapped by President Joe Biden in 2023 to head the agency, sought to end what he described as “grave injustices” that left people “in dire financial straits.”

In March 2024, O’Malley said the agency would stop “that clawback cruelty” of intercepting 100% of a beneficiary’s monthly check if they fail to respond to a demand for repayment. Instead, the agency would default to withholding 10% of the recipient’s monthly benefits, he said.

A year later, the Trump administration reversed that policy change, returning to 100% withholding for new overpayments. “It is our duty to revise the overpayment repayment policy back to full withholding, as it was during the Obama administration and first Trump administration, to properly safeguard taxpayer funds,” acting Commissioner Lee Dudek said in a March news release.

Now, in a pattern that has played out on multiple fronts during the first 100 days of President Donald Trump’s second term, the administration is partly reversing the reversal.

This time, it issued no news release.

“I think that we had the policy right before,” O’Malley said in an interview April 28. “We looked at the various break points, and if you would depend entirely on your Social Security check, having half of it interrupted means what? That means you go without paying your heating bill for the month; that means you’d go without your medicine instead of buying medicine and food.”

“So it was a cruelhearted policy before,” he added. At 50%, “it’s half as cruel, but it’s still cruel.”

Withholding even 50% of monthly benefits will “cause hardship for many older and disabled people,” said Kathleen Romig, who worked at the Social Security Administration under O’Malley and is now director of Social Security and disability policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “Going without half a Social Security check would make it harder for many people to afford basic needs like housing, food, and health care,” Romig said.

The SSA press office did not respond to questions for this article.

The emergency message to SSA staff said the new policy applies to overpayment notices sent on or after April 25. In one place, the message said the new withholding rate will be “up to 50 percent.” If the recipient does not request a lower rate of withholding, reconsideration, or a waiver — and “if there is no fraud or similar fault” — the agency will begin cutting their benefit payment after about 90 days, it said.

That does not apply to withholding of benefits in the Supplemental Security Income program, which serves people who have disabilities and older adults who have little or no income or resources, as the SSA explains. The agency said in March that withholding of SSI benefits would remain capped at 10%.

Kate Lang, director of federal income security at the advocacy group Justice in Aging, welcomed the shift from 100% withholding but said she was disappointed the agency didn’t revert to 10%. Lang called the agency’s conduct “chaotic and confusing.”

“It creates more work for SSA — more people calling with questions, more errors being made that need to be corrected, more confusion and uncertainty about what is going on,” Lang said.

“It’s a nightmare,” O’Malley said, “for not only the staff to have all of the switcheroo on policy, but also for the beneficiaries.”

Do you have an experience with Social Security overpayments you’d like to share? Click here to contact our reporting team.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

When Hospitals Ditch Medicare Advantage Plans, Thousands of Members Get To Leave, Too

For several years, Fred Neary had been seeing five doctors at the Baylor Scott & White Health system, whose 52 hospitals serve central and northern Texas, including Neary’s home in Dallas. But in October, his Humana Medicare Advantage plan — an alternative to government-run Medicare […]

Health CareFor several years, Fred Neary had been seeing five doctors at the Baylor Scott & White Health system, whose 52 hospitals serve central and northern Texas, including Neary’s home in Dallas. But in October, his Humana Medicare Advantage plan — an alternative to government-run Medicare — warned that Baylor and the insurer were fighting over a new contract. If they couldn’t reach an agreement, he’d have to find new doctors or new health insurance.

“All my medical information is with Baylor Scott & White,” said Neary, 87, who retired from a career in financial services. His doctors are a five-minute drive from his house. “After so many years, starting over with that many new doctor relationships didn’t feel like an option.”

After several anxious weeks, Neary learned Humana and Baylor were parting ways as of this year, and he was forced to choose between the two. Because the breakup happened during the annual fall enrollment period for Medicare Advantage, he was able to pick a new Advantage plan with coverage starting Jan. 1, a day after his Humana plan ended.

Other Advantage members who lose providers are not as lucky. Although disputes between health systems and insurers happen all the time, members are usually locked into their plans for the year and restricted to a network of providers, even if that network shrinks. Unless members qualify for what’s called a special enrollment period, switching plans or returning to traditional Medicare is allowed only at year’s end, with new coverage starting in January.

But in the past 15 months, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which oversees the Medicare Advantage program, has quietly offered roughly three-month special enrollment periods allowing thousands of Advantage members in at least 13 states to change plans. They were also allowed to leave Advantage plans entirely and choose traditional Medicare coverage without penalty, regardless of when they lost their providers. But even when CMS lets Advantage members leave a plan that lost a key provider, insurers can still enroll new members without telling them the network has shrunk.

At least 41 hospital systems have dropped out of 62 Advantage plans serving all or parts of 25 states since July, according to Becker’s Hospital Review. Over the past two years, separations between Advantage plans and health systems have tripled, said FTI Consulting, which tracks reports of the disputes.

CMS spokesperson Catherine Howden said it is “a routine occurrence” for the agency to determine that provider network changes trigger a special enrollment period for their members. “It has happened many times in the past, though we have seen an uptick in recent years.”

Still, CMS would not identify plans whose members were allowed to disenroll after losing health providers. The agency also would not say whether the plans violated federal provider network rules intended to ensure that Medicare Advantage members have sufficient providers within certain distances and travel times.

The secrecy around when and how Advantage members can escape plans after their doctors and hospitals drop out worries Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon, the senior Democrat on the Senate Finance Committee, which oversees CMS.

“Seniors enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans deserve to know they can change their plan when their local doctor or hospital exits the plan due to profit-driven business practices,” Wyden said.

The increase in insurer-provider breakups isn’t surprising, given the growing popularity of Medicare Advantage. The plans attracted about 54% of the 61.2 million people who had both Medicare Parts A and B and were eligible to sign up for Medicare Advantage in 2024, according to KFF, a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

The plans can offer supplemental benefits unavailable from traditional Medicare because the federal government pays insurers about 20% more per member than traditional Medicare per-member costs, according to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, which advises Congress. The extra spending, which some lawmakers call wasteful, will total about $84 billion in 2025, MedPAC estimates. While traditional Medicare does not offer the additional benefits Advantage plans advertise, it does not limit beneficiaries’ choice of providers. They can go to any doctor or hospital that accepts Medicare, as nearly all do.

Sanford Health, the largest rural health system in the U.S., serving parts of seven states from South Dakota to Michigan, decided to leave a Humana Medicare Advantage plan last year that covered 15,000 of its patients. “It’s not so much about the finances or administrative burden, although those are real concerns,” said Nick Olson, Sanford Health’s chief financial officer. “The most important thing for us is the fact that coverage denials and prior authorization delays impact the care a patient receives, and that’s unacceptable.”

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners, representing insurance regulators from every state, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia, has appealed to CMS to help Advantage members.

“State regulators in several states are seeing hospitals and crucial provider groups making decisions to no longer contract with any MA plans, which can leave enrollees without ready access to care,” the group wrote in September. “Lack of CMS guidance could result in unnecessary financial or medical injury to America’s seniors.”

The commissioners appealed again last month to Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. “Significant network changes trigger important rights for beneficiaries, and they should receive clear notice of their rights and have access to counseling to help them make appropriate choices,” they wrote.

The insurance commissioners asked CMS to consider offering a special enrollment period for all Advantage members who lose the same major provider, instead of placing the burden on individuals to find help on their own. No matter what time of year, members would be able to change plans or enroll in government-run Medicare.

Advantage members granted this special enrollment period who choose traditional Medicare get a bonus: If they want to purchase a Medigap policy — supplemental insurance that helps cover Medicare’s considerable out-of-pocket costs — insurers can’t turn them away or charge them more because of preexisting health conditions.

Those potential extra costs have long been a deterrent for people who want to leave Medicare Advantage for traditional Medicare.

“People are being trapped in Medicare Advantage because they can’t get a Medigap plan,” said Bonnie Burns, a training and policy specialist at California Health Advocates, a nonprofit watchdog that helps seniors navigate Medicare.

Guaranteed access to Medigap coverage is especially important when providers drop out of all Advantage plans. Only four states — Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maine, and New York — offer that guarantee to anyone who wants to reenroll in Medicare.

But some hospital systems, including Great Plains Health in North Platte, Nebraska, are so frustrated by Advantage plans that they won’t participate in any of them.

It had the same problems with delays and denials of coverage as other providers, but one incident stands out for CEO Ivan Mitchell: A patient too sick to go home had to stay in the hospital an extra six weeks because her plan wouldn’t cover care in a rehabilitation facility.

With traditional Medicare the only option this year for Great Plains Health patients, Nebraska insurance commissioner Eric Dunning asked for a special enrollment period with guaranteed Medigap access for some 1,200 beneficiaries. After six months, CMS agreed.

Once Delaware’s insurance commissioner contacted CMS about the Bayhealth medical system dropping out of a Cigna Advantage plan, members received a special enrollment period starting in January.

Maine’s congressional delegation pushed for an enrollment period for nearly 4,000 patients of Northern Light Health after the 10-hospital system dropped out of a Humana Advantage plan last year.

“Our constituents have told us that they are anticipating serious challenges, ranging from worries about substantial changes to cost-sharing rates to concerns about maintaining care with current providers,” the delegation told CMS.

CMS granted the request to ensure “that MA enrollees have access to medically necessary care,” then-CMS Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure wrote to Sen. Angus King (I-Maine).

Minnesota insurance officials appealed to CMS on behalf of some 75,000 members of Aetna, Humana, and UnitedHealthcare Advantage plans after six health systems announced last year they would leave the plans in 2025. So many provider changes caused “tremendous problems,” said Kelli Jo Greiner, director of the Minnesota State Health Insurance Assistance Program, known as a SHIP, at the Minnesota Board on Aging. SHIP counselors across the country provide Medicare beneficiaries free help choosing and using Medicare drug and Advantage plans.

Providers serving about 15,000 of Minnesota’s Advantage members ultimately agreed to stay in the insurers’ networks. CMS decided 14,000 Humana members qualified for a network-change special enrollment period.