KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': Cutting Medicaid Is Hard — Even for the GOP

The Host Julie Rovner KFF Health News @jrovner @julierovner.bsky.social Read Julie’s stories. Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the […]

Health Care

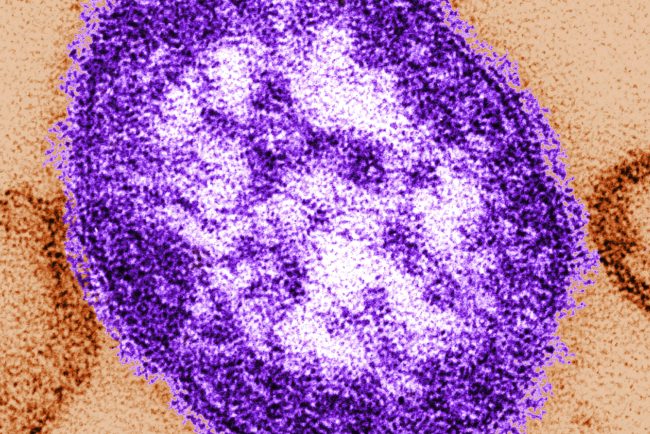

Ontario reports almost 200 new measles cases as virus spreads across Canada

That brings the province’s tally of probable and confirmed cases to 1,440 since an outbreak began in October.

Measles

Meet the Florida Group Chipping Away at Public Benefits One State at a Time

PHOENIX — As an Arizona bill to block people from using government aid to buy soda headed to the governor’s desk in April, the nation’s top health official joined Arizona lawmakers in the state Capitol to celebrate its passage. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert […]

Health Care

As Republicans Eye Sweeping Medicaid Cuts, Missouri Offers a Preview

CRESTWOOD, Mo. — The prospect of sweeping federal cuts to Medicaid is alarming to some Missourians who remember the last time the public medical insurance program for those with low incomes or disabilities was pressed for cash in the state. In 2005, Missouri adopted some […]

Health CareCRESTWOOD, Mo. — The prospect of sweeping federal cuts to Medicaid is alarming to some Missourians who remember the last time the public medical insurance program for those with low incomes or disabilities was pressed for cash in the state.

In 2005, Missouri adopted some of the strictest eligibility standards in the nation, reduced benefits, and increased patients’ copayments for the joint federal-state program due to state budget shortfalls totaling about $2.4 billion over several prior years. More than 100,000 Missourians lost coverage as a result, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia reported that the changes led to increases in credit card borrowing and debt in third-party collections.

A woman told NPR that year that her $6.70-an-hour McDonald’s job put her over the new income limits and rendered her ineligible, even though she was supporting three children on about $300 a week. A woman receiving $865 a month in disability payments worried at a town hall meeting about not being able to raise her orphaned granddaughter as the state asked her to pay $167 a month to keep her health coverage.

Now, Missouri could lose an estimated $2 billion a year in federal funding as congressional Republicans look to cut at least $880 billion over a decade from a pool of funding that includes Medicaid programs nationwide. Medicaid and the closely related Children’s Health Insurance Program together insure roughly 79 million people — about 1 in 5 Americans.

“We’re looking at a much more significant impact with the loss of federal funds even than what 2005 was,” said Amy Blouin, president of the progressive Missouri Budget Project think tank. “We’re not going to be able to protect kids. We’re not going to be able to protect people with disabilities from some sort of impact.”

At today’s spending levels, a cut of $880 billion to Medicaid could lead to states’ losing federal funding ranging from $78 million a year in Wyoming to $13 billion a year in California, according to an analysis from KFF, a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News. State lawmakers nationwide would then be left to address the shortfalls, likely through some combination of slashing benefits or eligibility, raising taxes, or finding a different large budget item to cut, such as education spending.

Republican lawmakers are floating various proposals to cut Medicaid, including one to reduce the money the federal government sends to states to help cover adults who gained access to the program under the Affordable Care Act’s provision known as Medicaid expansion. The 2010 health care law allowed states to expand Medicaid eligibility to cover more adults with low incomes. The federal government is picking up 90% of the tab for that group. About 20 million people nationwide are now covered through that expansion.

Missouri expanded Medicaid in 2021. That has meant that a single working-age adult in Missouri can now earn up to $21,597 a year and qualify for coverage, whereas before, nondisabled adults without children couldn’t get Medicaid coverage. That portion of the program now covers over 329,000 Missourians, more than a quarter of the state’s Medicaid recipients.

For every percentage point that the federal portion of the funding for that group decreases, Missouri’s Medicaid director estimated, the state could lose $30 million to $35 million a year.

But the equation is even more complicated given that Missouri expanded access via a constitutional amendment. Voters approved the expansion in 2020 after the state’s Republican leadership resisted doing so for a decade. That means changes to Medicaid expansion in Missouri would require voters to amend the state constitution again. The same is true in South Dakota and Oklahoma.

So even if Congress attempted to narrowly target cuts to the nation’s Medicaid expansion population, Washington University in St. Louis health economist Timothy McBride said, Missouri’s expansion program would likely stay in place.

“Then you would just have to find the money elsewhere, which would be brutal in Missouri,” McBride said.

In Crestwood, a suburb of St. Louis, Sandra Smith worries her daughter’s in-home nursing care would be on the chopping block. Nearly all in-home services are an optional part of Medicaid that states are not required to include in their programs. But the services have been critical for Sandra and her 24-year-old daughter, Sarah.

Sarah Smith has been disabled for most of her life due to seizures from a rare genetic disorder called Dravet syndrome. She has been covered by Medicaid in various ways since she was 3.

She needs intensive, 24-hour care, and Medicaid pays for a nurse to come to their home 13 hours a day. Her mother serves as the overnight caregiver and covers when the nurses are sick — work Sandra Smith is not allowed to be compensated for and that doesn’t count toward the 63-year-old’s Social Security.

Having nursing help allows Sandra Smith to work as an independent podcast producer and gives her a break from being the go-to-person for providing care 24 hours a day, day after day, year after year.

“I really and truly don’t know what I would do if we lost the Medicaid home care. I have no plan whatsoever,” Sandra Smith said. “It is not sustainable for anyone to do infinite, 24-hour care without dire physical health, mental health, and financial consequences, especially as we parents get into our elder years.”

Elias Tsapelas, director of fiscal policy at the conservative Show-Me Institute, said potential changes to Medicaid programs depend on the extent of any budget cuts that Congress ultimately passes and how much time states have to respond.

A large cut implemented immediately, for example, would require state legislators to look for parts of the budget they have the discretion to cut quickly. But if states have time to absorb funding changes, he said, they would have more flexibility.

“I’m not ready to think that Congress is going to willingly put us on the path of making every state go cut their benefits for the most vulnerable,” Tsapelas said.

Missouri’s congressional delegation split along party lines over the recent budget resolution calling for deep spending cuts, with the Republicans who control six of the eight House seats and both Senate seats all voting for it.

But 76% of the public, including 55% of Republicans, say they oppose major federal funding cuts to Medicaid, according to a national KFF poll conducted April 8-15.

And Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley, a Republican, has said that he does not support cutting Medicaid and posted on the social platform X that he was told by President Donald Trump that the House and Senate would not cut Medicaid benefits and that Trump won’t sign any benefit cuts.

“I hope congressional leadership will get the message,” Hawley posted. He declined to comment for this article.

U.S. House Republicans are aiming to pass a budget by Memorial Day, after many state legislatures, including Missouri’s, will have adjourned for the year.

Meanwhile, Missouri lawmakers are poised to pass a tax cut that is estimated to reduce state revenue by about $240 million in the first year.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Nova Scotia resident becomes province’s 1st measles case in 2 years after U.S. visit

Public health has released a list of possible exposure locations in downtown Halifax, including a hotel, a bar and the Halifax Infirmary ER.

MeaslesPublic health has released a list of possible exposure locations in downtown Halifax, including a hotel, a bar and the Halifax Infirmary ER.

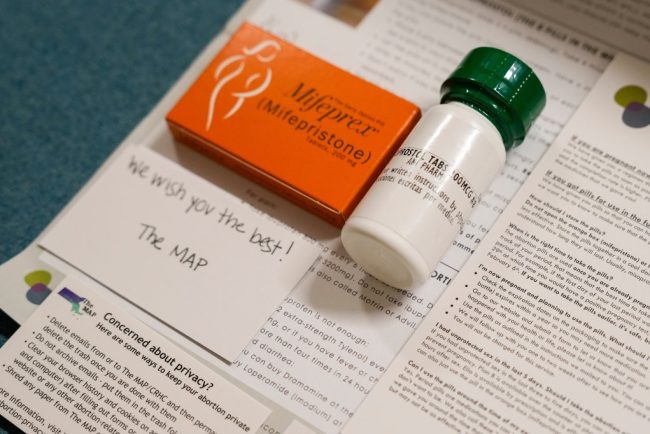

Despite Historic Indictment, Doctors Will Keep Mailing Abortion Pills Across State Lines

When the news broke on Jan. 31 that a New York physician had been indicted for shipping abortion medications to a woman in Louisiana, it stoked fear across the network of doctors and medical clinics who engage in similar work. “It’s scary. It’s frustrating,” said […]

PharmaceuticalsWhen the news broke on Jan. 31 that a New York physician had been indicted for shipping abortion medications to a woman in Louisiana, it stoked fear across the network of doctors and medical clinics who engage in similar work.

“It’s scary. It’s frustrating,” said Angel Foster, co-founder of the Massachusetts Medication Abortion Access Project, a clinic near Boston that mails mifepristone and misoprostol pills to patients in states with abortion bans. But, Foster added, “it’s not entirely surprising.”

Ever since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, abortion providers like her had been expecting prosecution or another kind of legal challenge from states with abortion bans, she said.

“It was unclear when those tests would come, and would it be against an individual provider or a practice or organization?” she said. “Would it be a criminal indictment, or would it be a civil lawsuit,” or even an attack on licensure? she wondered. “All of that was kind of unknown, and we’re starting to see some of this play out.”

The indictment also sparked worry among abortion providers like Kohar Der Simonian, medical director for Maine Family Planning. The clinic doesn’t mail pills into states with bans, but it does treat patients who travel from those states to Maine for abortion care.

“It just hit home that this is real, like this could happen to anybody, at any time now, which is scary,” Der Simonian said.

Der Simonian and Foster both know the indicted doctor, Margaret Carpenter.

“I feel for her. I very much support her,” Foster said. “I feel very sad for her that she has to go through all of this.”

On Jan. 31, Carpenter became the first U.S. doctor criminally charged for providing abortion pills across state lines — a medical practice that grew after the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision on June 24, 2022, which overturned Roe.

Since Dobbs, 12 states have enacted near-total abortion bans, and an additional 10 have outlawed the procedure after a certain point in pregnancy, but before a fetus is viable.

Carpenter was indicted alongside a Louisiana mother who allegedly received the mailed package and gave the pills prescribed by Carpenter to her minor daughter.

The teen wanted to keep the pregnancy and called 911 after taking the pills, according to an NPR and KFF Health News interview with Tony Clayton, the Louisiana local district attorney prosecuting the case. When police responded, they learned about the medication, which carried the prescribing doctor’s name, Clayton said.

On Feb. 11, Louisiana’s Republican governor, Jeff Landry, signed an extradition warrant for Carpenter. He later posted a video arguing she “must face extradition to Louisiana, where she can stand trial and justice will be served.”

New York’s Democratic governor, Kathy Hochul, countered by releasing her own video, confirming she was refusing to extradite Carpenter. The charges carry a possible five-year prison sentence.

“Louisiana has changed their laws, but that has no bearing on the laws here in the state of New York,” Hochul said.

Eight states — New York, Maine, California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington — have passed laws since 2022 to protect doctors who mail abortion pills out of state, and thereby block or “shield” them from extradition in such cases. But this is the first criminal test of these relatively new “shield laws.”

The telemedicine practice of consulting with remote patients and prescribing them medication abortion via the mail has grown in recent years — and is now playing a critical role in keeping abortion somewhat accessible in states with strict abortion laws, according to research from the Society of Family Planning, a group that supports abortion access.

Doctors who prescribe abortion pills across state lines describe facing a new reality in which the criminal risk is no longer hypothetical. The doctors say that if they stop, tens of thousands of patients would no longer be able to end early pregnancies safely at home, under the care of a U.S. physician. But the doctors could end up in the crosshairs of a legal clash over the interstate practice of medicine when two states disagree on whether people have a right to end a pregnancy.

Doctors on Alert but Remain Defiant

Maine Family Planning, a network of clinics across 19 locations, offers abortions, birth control, gender-affirming care, and other services. One patient recently drove over 17 hours from South Carolina, a state with a six-week abortion ban, Der Simonian said.

For Der Simonian, that case illustrates how desperate some of the practice’s patients are for abortion access. It’s why she supported Maine’s 2024 shield law, she said.

Maine Family Planning has discussed whether to start mailing abortion medication to patients in states with bans, but it has decided against it for now, according to Kat Mavengere, a clinic spokesperson.

Reflecting on Carpenter’s indictment, Der Simonian said it underscored the stakes for herself — and her clinic — of providing any abortion care to out-of-state patients. Shield laws were written to protect against the possibility that a state with an abortion ban charges and tries to extradite a doctor who performed a legal, in-person procedure on someone who had traveled there from another state, according to a review of shield laws by the Center on Reproductive Health, Law, and Policy at the UCLA School of Law.

“It is a fearful time to do this line of work in the United States right now,” Der Simonian said. “There will be a next case.” And even though Maine’s shield law protects abortion providers, she said, “you just don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Data shows that in states with total or six-week abortion bans, an average of 7,700 people a month were prescribed and took mifepristone and misoprostol to end their pregnancies by out-of-state doctors practicing in states with shield laws. The data, covering the second quarter of 2024, is part of a #WeCount report estimating the volume and types of abortions in the U.S., conducted by the Society of Family Planning.

Among Louisiana residents, nearly 60% of abortions took place via telemedicine in the second half of 2023 (the most recent period for which estimates are available), giving Louisiana the highest rate of telemedicine abortions among states that passed strict bans after Dobbs, according to the #WeCount survey.

Organizations like the Massachusetts Medication Abortion Access Project, known as the MAP, are responding to the demand for remote care. The MAP was launched after the Dobbs ruling, with the mission of writing prescriptions for patients in other states.

During 2024, the MAP says, it was mailing abortion medications to about 500 patients a month. In the new year, the monthly average has grown to 3,000 prescriptions a month, said Foster, the group’s co-founder.

The majority of the MAP’s patients — 80% — live in Texas or states in the Southeast, a region blanketed with near-total abortion restrictions, Foster said.

But the recent indictment from Louisiana will not change the MAP’s plans, Foster said. The MAP currently has four staff doctors and is hiring one more.

“I think there will be some providers who will step out of the space, and some new providers will step in. But it has not changed our practice,” Foster said. “It has not changed our intention to continue to practice.”

The MAP’s organizational structure was designed to spread potential liability, Foster said.

“The person who orders the pills is different than the person who prescribes the pills, is different from the person who ships the pills, is different from the person who does the payments,” she explained.

In 22 states and Washington, D.C., Democratic leaders helped establish shield laws or similarly protective executive orders, according to the UCLA School of Law review of shield laws.

The review found that in eight states, the shield law applies to in-person and telemedicine abortions. In the other 14 states plus Washington, D.C., the protections do not explicitly extend to abortion via telemedicine.

Most of the shield laws also apply to civil lawsuits against doctors. Over a month before Louisiana indicted Carpenter, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton filed a civil suit against her. A Texas judge ruled against Carpenter on Feb. 13, imposing penalties of more than $100,000.

By definition, state shield laws cannot protect doctors when they leave the state. If they move or even travel elsewhere, they lose the first state’s protection and risk arrest in the destination state, and maybe extradition to a third state.

Physicians doing this type of work accept there are parts of the U.S. where they should no longer go, said Julie F. Kay, a human rights lawyer who helps doctors set up telemedicine practices.

“There’s really a commitment not to visit those banned and restricted states,” said Kay, who worked with Carpenter to help start the Abortion Coalition for Telemedicine.

“We didn’t have anybody going to the Super Bowl or Mardi Gras or anything like that,” Kay said of the doctors who practice abortion telemedicine across state lines.

She said she has talked to other interested doctors who decided against doing it “because they have an elderly parent in Florida, or a college student somewhere, or family in the South.” Any visits, even for a relative’s illness or death, would be too risky.

“I don’t use the word ‘hero’ lightly or toss it around, but it’s a pretty heroic level of providing care,” Kay said.

Governors Clash Over Doctor’s Fate

Carpenter’s case remains unresolved. New York’s rebuff of Louisiana’s extradition request shows the state’s shield law is working as designed, according to David Cohen and Rachel Rebouché, law professors with expertise in abortion laws.

Louisiana officials, for their part, have pushed back in social media posts and media interviews.

“It is not any different than if she had sent fentanyl here. It’s really not,” Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill told Fox 8 News in New Orleans. “She sent drugs that are illegal to send into our state.”

Louisiana’s next step would be challenging New York in federal courts, according to legal experts across the political spectrum.

NPR and KFF Health News asked Clayton, the Louisiana prosecutor who charged Carpenter, whether Louisiana has plans to do that. Clayton declined to answer.

Case Highlights Fraught New Legal Frontier

A major problem with the new shield laws is that they challenge the basic fabric of U.S. law, which relies on reciprocity between states, including in criminal cases, said Thomas Jipping, a senior legal fellow with the Heritage Foundation, which supports a national abortion ban.

“This actually tries to undermine another state’s ability to enforce its own laws, and that’s a very grave challenge to this tradition in our country,” Jipping said. “It’s unclear what legal issues, or potentially constitutional issues, it may raise.”

But other legal scholars disagree with Jipping’s interpretation. The U.S. Constitution requires extradition only for those who commit crimes in one state and then flee to another state, said Cohen, a law professor at Drexel University’s Thomas R. Kline School of Law.

Telemedicine abortion providers aren’t located in states with abortion bans and have not fled from those states — therefore they aren’t required to be extradited back to those states, Cohen said. If Louisiana tries to take its case to federal court, he said, “they’re going to lose because the Constitution is clear on this.”

“The shield laws certainly do undermine the notion of interstate cooperation, and comity, and respect for the policy choices of each state,” Cohen said, “but that has long been a part of American law and history.”

When states make different policy choices, sometimes they’re willing to give up those policy choices to cooperate with another state, and sometimes they’re not, he said.

The conflicting legal theories will be put to the test if this case goes to federal court, other legal scholars said.

“It probably puts New York and Louisiana in real conflict, potentially a conflict that the Supreme Court is going to have to decide,” said Rebouché, dean of the Temple University Beasley School of Law.

Rebouché, Cohen, and law professor Greer Donley worked together to draft a proposal for how state shield laws might work. Connecticut passed the first law — though it did not include protections specifically for telemedicine. It was signed by the state’s governor in May 2022, over a month before the Supreme Court overturned Roe, in anticipation of potential future clashes between states over abortion rights.

In some shield-law states, there’s a call to add more protections in response to Carpenter’s indictment.

New York state officials have. On Feb. 3, Hochul signed a law that allows physicians to name their clinic as the prescriber — instead of using their own names — on abortion medications they mail out of state. The intent is to make it more difficult to indict individual doctors. Der Simonian is pushing for a similar law in Maine.

Samantha Glass, a family medicine physician in New York, has written such prescriptions in a previous job, and plans to find a clinic where she could offer that again. Once a month, she travels to a clinic in Kansas to perform in-person abortions.

Carpenter’s indictment could cause some doctors to stop sending pills to states with bans, Glass said. But she believes abortion should be as accessible as any other health care.

“Someone has to do it. So why wouldn’t it be me?” Glass said. “I just think access to this care is such a lifesaving thing for so many people that I just couldn’t turn my back on it.”

This article is from a partnership that includes WWNO, NPR, and KFF Health News.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

At Social Security, These Are the Days of the Living Dead

Rennie Glasgow, who has served 15 years at the Social Security Administration, is seeing something new on the job: dead people. They’re not really dead, of course. In four instances over the past few weeks, he told KFF Health News, his Schenectady, New York, office […]

Health CareRennie Glasgow, who has served 15 years at the Social Security Administration, is seeing something new on the job: dead people.

They’re not really dead, of course. In four instances over the past few weeks, he told KFF Health News, his Schenectady, New York, office has seen people come in for whom “there is no information on the record, just that they are dead.” So employees have to “resurrect” them — affirm that they’re living, so they can receive their benefits.

Revivals were “sporadic” before, and there’s been an uptick in such cases across upstate New York, said Glasgow. He is also an official with the American Federation of Government Employees, the union that represented 42,000 Social Security employees just before the start of President Donald Trump’s second term.

Martin O’Malley, who led the Social Security Administration toward the end of the Joe Biden administration, said in an interview that he had heard similar stories during a recent town hall in Racine, Wisconsin. “In that room of 200 people, two people raised their hands and said they each had a friend who was wrongly marked as deceased when they’re very much alive,” he said.

It’s more than just an inconvenience, because other institutions rely on Social Security numbers to do business, Glasgow said. Being declared dead “impacts their bank account. This impacts their insurance. This impacts their ability to work. This impacts their ability to get anything done in society.”

“They are terminating people’s financial lives,” O’Malley said.

Though it’s just one of the things advocates and lawyers worry about, these erroneous deaths come after a pair of initiatives from new leadership at the SSA to alter or update its databases of the living and the dead.

Holders of millions of Social Security numbers have been marked as deceased. Separately, according to The Washington Post and The New York Times, thousands of numbers belonging to immigrants have been purged, cutting them off from banks and commerce, in an effort to encourage these people to “self-deport.”

Glasgow said SSA employees received an agency email in April about the purge, instructing them how to resurrect beneficiaries wrongly marked dead. “Why don’t you just do due diligence to make sure what you’re doing in the first place is correct?” he said.

The incorrectly marked deaths are just a piece of the Trump administration’s crash program purporting to root out fraud, modernize technology, and secure the program’s future.

But KFF Health News’ interviews with more than a dozen beneficiaries, advocates, lawyers, current and former employees, and lawmakers suggest the overhaul is making the agency worse at its primary job: sending checks to seniors, orphans, widows, and those with disabilities.

Philadelphian Lisa Seda, who has cancer, has been struggling for weeks to sort out her 24-year-old niece’s difficulties with Social Security’s disability insurance program. There are two problems: first, trying to change her niece’s address; second, trying to figure out why the program is deducting roughly $400 a month for Medicare premiums, when her disability lawyer — whose firm has a policy against speaking on the record — believes they could be zero.

Since March, sometimes Social Security has direct-deposited payments to her niece’s bank account and other times mailed checks to her old address. Attempting to sort that out has been a morass of long phone calls on hold and in-person trips seeking an appointment.

Before 2025, getting the agency to process changes was usually straightforward, her lawyer said. Not anymore.

The need is dire. If the agency halts the niece’s disability payments, “then she will be homeless,” Seda recalled telling an agency employee. “I don’t know if I’m going to survive this cancer or not, but there is nobody else to help her.”

Some of the problems are technological. According to whistleblower information provided to Democrats on the House Oversight Committee, the agency’s efforts to process certain data have been failing more frequently. When that happens, “it can delay or even stop payments to Social Security recipients,” the committee recently told the agency’s inspector general.

While tech experts and former Social Security officials warn about the potential for a complete system crash, day-to-day decay can be an insidious and serious problem, said Kathleen Romig, formerly of the Social Security Administration and its advisory board and currently the director of Social Security and disability policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Beneficiaries could struggle to get appointments or the money they’re owed, she said.

For its more than 70 million beneficiaries nationwide, Social Security is crucial. More than a third of recipients said they wouldn’t be able to afford necessities if the checks stopped coming, according to National Academy of Social Insurance survey results published in January.

Advocates and lawyers say lately Social Security is failing to deliver, to a degree that’s nearly unprecedented in their experience.

Carolyn Villers, executive director of the Massachusetts Senior Action Council, said two of her members’ March payments were several days late. “For one member that meant not being able to pay rent on time,” she said. “The delayed payment is not something I’ve heard in the last 20 years.”

When KFF Health News presented the agency with questions, Social Security officials passed them off to the White House. White House spokesperson Elizabeth Huston referred to Trump’s “resounding mandate” to make government more efficient.

“He has promised to protect social security, and every recipient will continue to receive their benefits,” Huston said in an email. She did not provide specific, on-the-record responses to questions.

Complaints about missed payments are mushrooming. The Arizona attorney general’s office had received approximately 40 complaints related to delayed or disrupted payments by early April, spokesperson Richie Taylor told KFF Health News.

A Connecticut agency assisting people on Medicare said complaints related to Social Security — which often helps administer payments and enroll patients in the government insurance program primarily for those over age 65 — had nearly doubled in March compared with last year.

Lawyers representing beneficiaries say that, while the historically underfunded agency has always had its share of errors and inefficiencies, it’s getting worse as experienced employees have been let go.

“We’re seeing more mistakes being made,” said James Ratchford, a lawyer in West Virginia with 17 years’ experience representing Social Security beneficiaries. “We’re seeing more things get dropped.”

What gets dropped, sometimes, are records of basic transactions. Kim Beavers of Independence, Missouri, tried to complete a periodic ritual in February: filling out a disability update form saying she remains unable to work. But her scheduled payments in March and April didn’t show.

She got an in-person appointment to untangle the problem — only to be told there was no record of her submission, despite her showing printouts of the relevant documents to the agency representative. Beavers has a new appointment scheduled for May, she said.

Social Security employees frequently cite missing records to explain their inability to solve problems when they meet with lawyers and beneficiaries. A disability lawyer whose firm’s policy does not allow them to be named had a particularly puzzling case: One client, a longtime Social Security disability recipient, had her benefits reassessed. After winning on appeal, the lawyer went back to the agency to have the payments restored — the recipient had been going without since February. But there was nothing there.

“To be told they’ve never been paid benefits before is just chaos, right? Unconditional chaos,” the lawyer said.

Researchers and lawyers say they have a suspicion about what’s behind the problems at Social Security: the Elon Musk-led effort to revamp the agency.

Some 7,000 SSA employees have reportedly been let go; O’Malley has estimated that 3,000 more would leave the agency. “As the workloads go up, the demoralization becomes deeper, and people burn out and leave,” he predicted in an April hearing held by House Democrats. “It’s going to mean that if you go to a field office, you’re going to see a heck of a lot more empty, closed windows.”

The departures have hit the agency’s regional payment centers hard. These centers help process and adjudicate some cases. It’s the type of behind-the-scenes work in which “the problems surface first,” Romig said. But if the staff doesn’t have enough time, “those things languish.”

Languishing can mean, in some cases, getting dropped by important programs like Medicare. Social Security often automatically deducts premiums, or otherwise administers payments, for the health program.

Lately, Melanie Lambert, a senior advocate at the Center for Medicare Advocacy, has seen an increasing number of cases in which the agency determines beneficiaries owe money to Medicare. The cash is sent to the payment centers, she said. And the checks “just sit there.”

Beneficiaries lose Medicare, and “those terminations also tend to happen sooner than they should, based on Social Security’s own rules,” putting people into a bureaucratic maze, Lambert said.

Employees’ technology is more often on the fritz. “There’s issues every single day with our system. Every day, at a certain time, our system would go down automatically,” said Glasgow, of Social Security’s Schenectady office. Those problems began in mid-March, he said.

The new problems leave Glasgow suspecting the worst. “It’s more work for less bodies, which will eventually hype up the inefficiency of our job and make us, make the agency, look as though it’s underperforming, and then a closer step to the privatization of the agency,” he said.

Jodie Fleischer of Cox Media Group contributed to this report.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

HIV Testing and Outreach Falter as Trump Funding Cuts Sweep the South

JACKSON, Miss. — Storm clouds hung low above a community center in Jackson, where pastor Andre Devine invited people inside for lunch. Hoagies with smoked turkey and ham drew the crowd, but several people lingered for free preventive health care: tests for HIV and other […]

Health CareJACKSON, Miss. — Storm clouds hung low above a community center in Jackson, where pastor Andre Devine invited people inside for lunch. Hoagies with smoked turkey and ham drew the crowd, but several people lingered for free preventive health care: tests for HIV and other diseases, flu shots, and blood pressure and glucose monitoring.

Between greetings, Devine, executive director of the nonprofit group Hearts for the Homeless, commiserated with his colleagues about the hundreds of thousands of dollars their groups had lost within a couple of weeks, swept up in the Trump administration’s termination of research dollars and clawback of more than $11 billion from health departments across the country.

Devine would have to scale back food distribution for people in need. And his colleagues at the nonprofit health care group My Brother’s Keeper were worried they’d have to shutter the group’s mobile clinic — an RV offering HIV tests, parked beside the community center that morning. Several employees had already been furloughed and the cuts kept coming, said June Gipson, CEO of My Brother’s Keeper.

“People can’t work without being paid,” she said.

The directors of other community-based groups in Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and Tennessee told KFF Health News they too had reduced their spending on HIV testing and outreach because of delayed or slashed federal funds — or they were making plans to do so, anticipating cuts to come.

Scaling back these efforts could prove tragic, Gipson said. Without an extra boost of support to get tested or stay on treatment, many people living with HIV will grow sicker and stand a greater chance of infecting others.

President Donald Trump, in his first term, promised to end America’s HIV epidemic — and he put the resources of the federal government behind the effort. This time, he has deployed the powers of his office to gut funding, abandoning those communities at highest risk of HIV.

Trump’s earlier efforts targeted seven Southern states, including Mississippi, where funds went to community groups and health departments that tailor interventions to historically underserved communities that face discrimination and have less access to quality education, health care, stable income, and generational wealth. Such factors help explain why Black people accounted for 38% of HIV diagnoses in the United States in 2023, despite representing only 14% of the population, and also why half of the country’s new HIV infections occur in the South.

Now, Trump is undermining HIV efforts by barring funds from programs built around diversity, equity, and inclusion. A Day One executive order said they represent “immense public waste and shameful discrimination.”

Since then, his administration has cut millions of dollars in federal grants to health departments, universities, and nonprofit organizations that do HIV work. And in April, it eliminated half of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 10 HIV branch offices, according to an email to grant recipients, reviewed by KFF Health News, from the director of the CDC’s Division of HIV Prevention. The layoffs included staff who had overseen the rollout of HIV grants to health departments and community-based groups, like My Brother’s Keeper.

The CDC provides more than 90% of all federal funding for HIV prevention — about $1 billion annually. The Trump administration’s May 2 budget proposal for fiscal 2026 takes aim at DEI initiatives, including in its explanation for cutting $3.59 billion from the CDC. Although the proposal doesn’t mention HIV prevention specifically, the administration’s drafted plan for HHS, released mid-April, eliminates all prevention funding at the CDC, as well as funding for Trump’s initiative to end the epidemic.

Eliminating federal funds for HIV prevention would lead to more than 143,000 additional people in the U.S. becoming infected with HIV within five years, and about 127,000 additional people who die of AIDS-related causes, according to estimates from the Foundation for AIDS Research, a nonprofit known as amfAR. Excess medical costs would exceed $60 billion, it said.

Eldridge Dwayne Ellis, the coordinator of the mobile testing clinic at My Brother’s Keeper, said curbing the group’s services goes beyond HIV.

“People see us as their only outlet, not just for testing but for confidential conversations, for a shoulder to cry on,” he said. “I don’t understand how someone, with the stroke of a pen, could just haphazardly write off the health of millions.”

Quiet Tears

Ellis came into his role in the mobile clinic haphazardly, when he worked as a construction worker. Suddenly dizzy and unwell on a job, a co-worker suggested he visit the organization’s brick-and-mortar clinic nearby. He later applied for a position with My Brother’s Keeper, inspired by its efforts to give people support to help themselves.

For example, Ellis described a young man who visited the mobile clinic recently who had been kicked out of his home and was sleeping on couches or on the street. Ellis thought of friends he’d known in similar situations that put them at risk of HIV by increasing the likelihood of transactional sex or substance use disorders.

When a rapid test revealed HIV, the young man fell silent. “The quiet tears hurt worse — it’s the dread of mortality,” Ellis said. “I tried to be as strong as possible to let him know his life is not over, that this wasn’t a death sentence.”

Ellis and his team enrolled the man into HIV care that day and stayed in touch. Otherwise, Ellis said, he might not have had the means or fortitude to seek treatment on his own and adhere to daily HIV pills. Not only is that deadly for people with HIV, it’s bad for public health. HIV experts use the phrase “treatment as prevention” because most new infections derive from people who aren’t adhering to treatment well enough to be considered virally suppressed — which keeps the disease from spreading.

Only a third of people living with HIV in Mississippi were virally suppressed in 2022. Nationally, that number is about 65%. That’s worse than in eastern and southern Africa, where 78% of people with HIV aren’t spreading the virus because they’re on steady treatment.

My Brother’s Keeper is one of many groups improving such numbers by helping people get tested and stay on medication. But the funding cuts in Washington have curtailed their work. The first loss was a $12 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, not even two years into a 10-year project. “Programs based primarily on artificial and non-scientific categories, including amorphous equity objectives, are antithetical to the scientific inquiry,” the NIH said in a letter reviewed by KFF Health News.

My Brother’s Keeper then lost a CDC award to reduce health disparities — a grant channeled through the Mississippi state health department — that began with the group’s work during the covid pandemic but had broadened to screening and care for HIV, heart disease, and diabetes. These are some of the maladies that account for why low-income Black people in the Deep South die sooner, on average, than those who are white. According to a recent study, the former’s life expectancy was just 68 years in 2021, on par with the average in impoverished nations like Rwanda and Myanmar.

The group then lost CDC funding that covered the cost of laboratory work to detect HIV, chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis in patients’ blood samples. Mississippi has the highest rate of sexually transmitted diseases among states, in part because people spread infections when they aren’t tested and treated.

“The labs are $200 to $600 per person,” Gipson said, “so now we can’t do that without passing the cost to the patient, and some can’t pay.”

Two other CDC grants on HIV prevention, together worth $841,000, were unusually delayed.

Public health specialists close to the CDC, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they fear retaliation, said they were aware of delays in HIV prevention funding, despite court orders to unfreeze payments for federal grants in January and February. “The faucet was being turned off at a higher level than at the CDC,” one specialist said. The delays have now been compounded, they said, by the gutting of that agency’s HIV workforce in April.

“I know of many organizations reliant on subcontracted federal funds who have not been paid for the work they’ve done, or whose funding has been terminated,” said Dafina Ward, executive director of the Southern AIDS Coalition.

To reach the underserved, these groups offer food, housing assistance, bus passes, disease screening, and a sense of community. A network of the groups was fostered, in part, by Trump’s initiative to end the epidemic. And it showed promise: From 2017 to 2022, new HIV infections decreased by 21% in the cities and the Southern states it targeted.

Disparities in infections were still massive, with the rate of HIV diagnoses about eight times as high for Black people as white people, and the South remained hardest hit. Ward was hopeful at the start of this year, however, as testing became more widespread and HIV prevention drugs — called preexposure prophylaxis, or PrEP — slowly gained popularity. But her outlook has shifted and she fears that grassroots organizations might not weather the funding turmoil.

“We’re seeing an about-face of what it means to truly work towards ending HIV in this country,” she said.

A Closed Clinic

Southeast of Jackson, in Hattiesburg, Sean Fortenberry tears up as he walks into a small room used until recently for HIV testing. He has kept his job at Mississippi’s AIDS Services Coalition by shifting his role but agonizes about the outcome. When Fortenberry tested positive for HIV in 2007, he said, his family and doctor saved his life.

“I never felt that I was alone, and that was really, really important,” he said. “Other people don’t have that, so when I came across this position, I was gung-ho. I wanted to help.”

But the coalition froze its HIV testing clinic and paused mobile testing at homeless shelters, colleges, and churches late last year. Kathy Garner, the group’s executive director, said the Mississippi health department — which funds the coalition with CDC’s HIV prevention dollars — told her to pause outreach in October before the state renewed the group’s annual HIV prevention contract.

Kendra Johnson, communicable diseases director at Mississippi’s health department, said that delays in HIV prevention funds were initially on the department’s end because it was short on administrative staff. Then Trump took office. “We were working with our federal partners to ensure that our new objectives were in line with new HIV prevention activities,” Johnson said. “And we ran into additional delays due to paused communications at the federal level.”

The AIDS coalition remains afloat largely because of federal money from the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program for treatment and from the Department of Housing and Urban Development. “If most of these federal dollars are cut, we would have to close,” Garner said.

The group provides housing or housing assistance to roughly 400 people each year. Research shows that people in stable housing adhere much better to HIV treatment and are far less likely to die than unhoused people with HIV.

Funding cuts have shaken every state, but the South is acutely vulnerable when it comes to HIV, said Gregorio Millett, director of public policy at amfAR. Southern states have the highest level of poverty and a severe shortage of rural clinics, and several haven’t expanded Medicaid so that more low-income adults have health insurance.

Further, Southern states aren’t poised to make up the difference. Alabama, Louisiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Missouri put zero state funds into HIV prevention last year, according to NASTAD, an association of public health officials who administer HIV and hepatitis programs. In contrast, about 40% of Michigan’s HIV prevention budget is provided by the state, 50% of Colorado’s HIV prevention budget, and 88% of New York’s.

“When you are in the South, you need the federal government,” said Gipson, from My Brother’s Keeper. “When we had slavery, we needed the federal government. When we had the push for civil rights, we needed the federal government. And we still need the federal government for health care,” she said. “The red states are going to suffer, and we’re going to start suffering sooner than anyone else.”

‘So Goes Mississippi’

When asked about cuts and delays to HIV prevention funding, the CDC directed queries to HHS. The department’s director of communications, Andrew Nixon, replied in an email: “Critical HIV/AIDS programs will continue under the Administration for a Healthy America (AHA) as a part of Secretary [Robert F.] Kennedy’s vision to streamline HHS to better serve the American people.”

Nixon did not reply to a follow-up question on whether the Trump administration considers HIV prevention critical.

On April 4, Gipson received a fraction of her delayed HIV prevention funds from the CDC. But Gipson said she was afraid to hire back staff amid the turmoil.

Like the directors of many other community organizations, Gipson is going after grants from foundations and companies. Pharmaceutical firms such as Gilead and GSK that produce HIV drugs are among the largest contributors of non-governmental funds for HIV testing, prevention, and care, but private funding for HIV has never come close to the roughly $40 billion that the federal government allocated to HIV annually.

“If the federal government withdraws some or all of its support, the whole thing will collapse,” said Alice Riener, CEO of the community-based organization CrescentCare in Louisiana. “What you see in Mississippi is the beginning of that, and what’s so concerning is the infrastructure we’ve built will collapse quickly but take decades to rebuild.”

Southern health officials are reeling from cuts because state budgets are already tight. Mississippi’s state health officer, Daniel Edney, spoke with KFF Health News on the day the Trump administration terminated $11 billion in covid-era funds intended to help states improve their public health operations. “There’s not a lot of fat, and we’re cutting it to the bone right now,” Edney said.

Mississippi needed this boost, Edney said, because the state ranks among the lowest in health metrics including premature death, access to clinical care, and teen births. But Edney noted hopeful trends: The state had recently moved from 50th to 49th worst in health rankings, and its rate of new HIV cases was dropping.

“The science tells us what we need to do to identify and care for patients, and we’re improving,” he said. “But trends can change very quickly on us, so we can’t take our foot off the gas pedal.”

If that happens, researchers say, the comeback of HIV will go unnoticed at first, as people at the margins of society are infected silently before they’re hospitalized. As untreated infections spread, the rise will eventually grow large enough to make a dent in national statistics, a resurgence that will cost lives and take years, if not decades, to reverse.

Outside the community center on that stormy March morning, pastor Devine lamented not just the loss of his grant from the health department, but a $1 billion cut to food distribution programs at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. He rattled off consequences he feared: People relying on food assistance would be forced to decide between buying groceries, paying bills, or seeing a doctor, driving them further into poverty, into emergency rooms, into crime.

Deja Abdul-Haqq, a program director at My Brother’s Keeper, nodded along as he spoke. “So goes Mississippi, so goes the rest of the United States,” Abdul-Haqq said. “Struggles may start here, but they spread.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Trump Team’s $500 Million Bet on Old Vaccine Technology Puzzles Scientists

The Trump administration’s unprecedented $500 million grant for a broadly protective flu shot has confounded vaccine and pandemic preparedness experts, who said the project was in early stages, relied on old technology, and was just one of more than 200 such efforts. Health and Human […]

PharmaceuticalsThe Trump administration’s unprecedented $500 million grant for a broadly protective flu shot has confounded vaccine and pandemic preparedness experts, who said the project was in early stages, relied on old technology, and was just one of more than 200 such efforts.

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. shifted the money from a pandemic preparedness fund to a vaccine development program led by two scientists whom the administration recently named to senior positions at the National Institutes of Health.

While some experts were pleased that Kennedy had supported any vaccine project, they said the May 1 announcement contravened sound scientific policy, appeared arbitrary, and raised the kinds of questions about conflicts of interest that have dogged many of President Donald Trump’s actions.

Focusing vast resources on a single vaccine candidate “is a little like going to the Kentucky Derby and putting all your money on one horse,” said William Schaffner, a Vanderbilt University professor and past president of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. “In science we normally put money on a number of different horses because we can’t be entirely sure who’s going to win.”

Others were mystified by the decision, since the candidate vaccine uses technology that was largely abandoned in the 1970s and eschews techniques developed in recent decades through funding from the Department of Health and Human Services and the Defense Department.

“This is not a next-generation vaccine,” said Rick Bright, who led HHS’ Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, or BARDA, in the first Trump administration. “It’s so last-generation, or first-generation, it’s mind-blowing.”

The vaccine is being developed at the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases by Jeffery Taubenberger, whom Trump named as acting chief of the institute in late April, and his colleague Matthew Memoli, a critic of U.S. covid-19 policy whom Trump picked to lead the NIH until April 1, when Jay Bhattacharya took office. Bhattacharya named Memoli his principal deputy.

Taubenberger gained fame as an Armed Forces Institute of Pathology scientist in 1997 when his lab sequenced the genome of the 1918 pandemic influenza virus, using tissue samples from U.S. troops who died in that plague. He joined the NIH in 2006.

In a May 1 news release, HHS called the Taubenberger-Memoli vaccine initiative “Generation Gold Standard,” saying it represented “a decisive shift toward transparency, effectiveness, and comprehensive preparedness.” Bhattacharya said it represented a “paradigm shift.”

But the NIH vaccine-makers’ goal of creating a shot that protects against multiple or all strains of influenza — currently vaccines must be given each year to account for shifts in the virus — is not new.

Then-NIAID Director Anthony Fauci launched a network of academic researchers in pursuit of a broadly protective flu vaccine in 2019. In addition to that NIH-led consortium, more than 200 flu vaccines are under development in the U.S. and other countries.

Many use newer technologies, and some are at more advanced stages of human testing than the Taubenberger vaccine, whose approach appears basically the same as the one used in flu vaccines starting in 1944, Bright said.

In the news release, HHS described the vaccine as “in advanced trials” and said it would induce “robust” responses and “long-lasting protection.” But Taubenberger and his colleagues haven’t published a complete human study of the vaccine yet. A study showing the vaccine protected mice from the flu appeared in 2022.

For Operation Warp Speed, which led to the creation of the covid vaccine during Trump’s first term, government scientists reviewed detailed plans and data from academic and commercial laboratories vying for federal money, said Greg Poland, a flu expert and president of the Atria Health Academy of Science and Medicine. “If that’s happening here, it’s opaque to me,” he said.

When asked what data beyond its press release supported the decision, HHS spokesperson Andrew Nixon pointed to the agency’s one-page statement. Asked whether the decision would curtail funding for the Fauci-created consortium or other universal vaccine approaches, Nixon did not specifically respond. “Generation Gold Standard is the most promising,” he said in an email.

Taubenberger did not respond to a request for comment. Nixon and NIH spokesperson Amanda Fine did not respond to requests for an interview with Taubenberger or Memoli.

The HHS statement stressed that by developing the vaccine in-house, the government “ensures radical transparency, public accountability, and freedom from commercial conflicts of interest.” While any vaccine would eventually have to be made commercially, NIH involvement through more stages of development could give the government greater influence on any vaccine’s eventual price, Schaffner said.

If the mRNA-based covid shots produced by Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech represented the cutting edge of vaccine technology, applying ultra-sophisticated approaches never before seen in an inoculation, the approach by Taubenberger and Memoli represents a blast from the past.

Their vaccine is made by inactivating influenza viruses with a carcinogenic chemical called beta-propiolactone. Scientists have used the chemical to neutralize viruses since at least the 1950s. This whole-virus inactivation method, mostly using other chemicals, was the standard way to make flu vaccines into the 1970s, when it was modified, partly because whole-virus vaccines caused high fevers or even seizures in children.

The limited published data from the Taubenberger vaccine, from an initial safety trial involving 45 patients, showed no major side effects. The scientists are testing the vaccine as a regular shot and as an intranasal spray with the idea of stopping the virus in the respiratory tract before it causes a broad infection.

“The notion of a universal influenza A pandemic vaccine is a good one,” said Poland, who called Taubenberger an excellent scientist. But he added: “I’m not so sure about the platform, and the dollar amount is a puzzler. This vaccine’s in very early development.”

Paul Friedrichs, a retired Air Force general who led the Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy in President Joe Biden’s White House, said that “giving $500 million upfront with very little data to support it is unlike anything I’ve ever seen.”

“The technology for developing vaccines has tremendously evolved over many decades,” Friedrichs said. “Why would we go back to an approach historically associated with greater or more frequent adverse events?”

The government appeared to be transferring the money for the Taubenberger vaccine development from an existing $1.3 billion vaccine fund at Project NextGen, a mostly covid-focused program at BARDA, Friedrichs said. Most of that money was earmarked to support advanced research on covid and other viral vaccines, including those protecting against emerging diseases.

It is “very concerning that we’re de-emphasizing covid, which we may live to regret,” Poland said. “It assumes we won’t have a covid variant that escapes the current moderately high levels of covid immunity.”

Nixon said Project NextGen, for which some funds were earmarked for mRNA research, is under review. Kennedy is critical of mRNA vaccines, once claiming, falsely, that they are the deadliest vaccines in history.

Ted Ross, director of global vaccine development at the Cleveland Clinic, said he was “happy to see them investing in respiratory vaccines, including a universal flu vaccine, with all the programs they’ve been cutting.”

“But I don’t think this is the only approach,” Ross said. “Other universal flu vaccines are in progress, and their success and failure are not known yet.”

His team, part of the NIAID-funded flu vaccine consortium, is using artificial intelligence and computer modeling to design vaccines that produce the broadest immunity to influenza, including seasonal and pandemic strains.

As interim director, Memoli oversaw the start of the administration’s massive cuts at the NIH, with the elimination of some 800 agency grants worth over $2 billion. More than 1,200 NIH employees have been fired, and many researchers, including Ross, are in limbo.

His lab is close to testing a candidate vaccine on people, Ross said, while waiting to find out about its NIH funding. “I’m not sure whether my contract is on the chopping block,” he said.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

An Arm and a Leg: Why ‘The Pitt’ Is Our Fave New Drama

People who work in real-life emergency rooms have raved about how the new TV drama “The Pitt” accurately captures the complex dynamics of their workplaces and the medical details of their cases. Host Dan Weissmann talks with Alex Janke, an emergency medicine doctor and health […]

Health CarePeople who work in real-life emergency rooms have raved about how the new TV drama “The Pitt” accurately captures the complex dynamics of their workplaces and the medical details of their cases.

Host Dan Weissmann talks with Alex Janke, an emergency medicine doctor and health policy researcher, about how the show stacks up against his experiences in the ER. They also discuss its depictions of the financial forces that shape day-to-day problems inside ERs.

Dan Weissmann

Host and producer of “An Arm and a Leg.” Previously, Dan was a staff reporter for Marketplace and Chicago’s WBEZ. His work also appears on All Things Considered, Marketplace, the BBC, 99 Percent Invisible, and Reveal, from the Center for Investigative Reporting.

Credits

Emily Pisacreta, Claire Davenport

Producers

Adam Raymonda

Audio wizard

Ellen Weiss

Editor

Click to open the Transcript

Transcript: Why ‘The Pitt’ Is Our Fave New Drama

Note: “An Arm and a Leg” uses speech-recognition software to generate transcripts, which may contain errors. Please use the transcript as a tool but check the corresponding audio before quoting the podcast.

Dan: Hey there. I’ve got a new favorite TV show: “The Pitt.” I signed up for HBO — Max, whatever –thats what my editor says I’m supposed to call it. The show takes place in a Pittsburgh emergency room, and the first season follows the staff through a single, jam-packed day, hour by hour. It’s riveting. Noah Wyle, who got famous playing a young doctor on the show ER in the 1990s, stars here as the senior doc on duty. And people who work in emergency rooms say it gets a lot of things right, including medical details that fly past most of us in scenes like this…

Doctor 1: Bring me up to speed?

Doctor 2: Intubated for agonal respirations. GCS five, probably anticoagulated. Doctor 1: With what?

Doctor 3: First time here. There’s no medical records.

Doctor 1: Call for FFP.

Doctor 2: No, we got four factors…

Dan: And yeah, I basically did not catch any of that. But when I played it for an actual ER doctor, Alex Janke, he kept smiling and nodding along. In any case, those were not the kinds of scenes I called Alex Janke to talk about. Because what drew me to the Pitt — for professional purposes at least — are scenes that show the bigger-picture forces — the financial forces — that MAKE this day, and every day, so difficult for the people who work in big-city ERs, and for the people who show up needing care. Forces that make ERs more crowded, and more chaotic. Less safe, and more expensive. I called Alex Janke because on top of working shifts at ERs, he does research on those forces as a professor at the University of Michigan.

Alex Janke: I care a lot about. Emergency medicine. Like I think that what we do is really, really special. And I also think that if you want to understand the problems in the world, you should come to the emergency department,’cause that’s where people go when they have problems.

Dan: Problems like gun violence, homelessness, sex trafficking,drug addiction, and a likely hate crime bring patients to The Pitt throughout the season. The Pitt also looks at questions that Alex studies: Why do people have to wait so long to get seen at ERs? How badly can those long wait-times affect our health? So, we watched some scenes that address those questions together and Alex was like…

Alex Janke: I’ve gotta find the people that made this show. This is so crazy. They, they’ve gotta have some docs working for them.

Dan: There’s a whole team. There’s a whole team.

Dan: Alex Janke thinks the producers picked the right team… because, he says: This is too real. So here comes a debrief. Basically free of spoilers — in terms of the MEDICAL drama. And I’ll tell you right now: The financial problems? Those storylines do not get wrapped up on The Pitt, or in real life. But the show does help us understand them, and what they cost all of us– doctors, patients, everybody– in money, in our health, and in our emotional well-being.

This is An Arm and a Leg, a show about why health care costs so freaking much, and what we can maybe do about it. I’m Dan Weissmann. I’m a reporter, and I like a challenge. So the job we’ve chosen on this show is to take one of the most enraging, terrifying, depressing parts of American life, and bring you something entertaining, empowering, and useful.

The folks who made “The Pitt” made a super-canny choice: The show follows a single day in this ER — and it happens to be the first day for a crew of new residents and interns. So while we watch them get shown around, we get a tour. First stop, the waiting room. It’s PACKED. A second-year resident explains how patients register, get a quick assessment…

Doctor: And then they come back to waiting room till bed opens up Doctor 2: For how long?

Doctor: Eight hours if they’re lucky. A lot of times 12.

Doctor 3: Ah, is it always this busy?

Doctor: Uh, no. It gets a lot busier.

Dan: Here’s Alex’s take on that snapshot.

Alex Janke: I think this is entirely real. And we can really expect this to be true going into the future that, uh, you know, eight hour waits, 12 hour waits, very high rates of left without being seen are just gonna keep happening all over the country. And it’s not gonna be every day that you walk in the door. but it’s gonna keep happening.

Dan: Why?

Alex Janke: That’s a great question.

Dan: Alex has a couple of answers. One is about demographics: We’ve got more folks now who are old, with complex medical issues than ever before, and that’s only gonna get more true for a long time to come. The other basically gets dramatized in the next couple scenes we watch. First, Noah Wyle’s character, the senior MD on this shift, Dr. Michael Rabinovich — everybody calls him Doctor Robby – gives the newbies his briefing. Here’s the first thing he tells them.

Robby: As you can see, our house is always packed and our department is mostly clogged up with borders. Those are admitted patients waiting for a room upstairs sometimes for days.

Dan: OK, that went by quick, but Dr Robby basically just described WHY people wait eight hours, twelve hours, why this ER and its waiting room is so full. I’ll let Alex explain.

Alex Janke: The emergency department is not full because folks with the sniffles came in when they could have gone to an urgent care. That is not the reason that the ER is crowded. Those patients are so easy, we see ’em out in triage. I love seeing those patients ’cause that’s somebody that I can

get in and out. I can take really good care of that patient sometimes just from the waiting room. The ER is full because there are folks that need to be in the hospital or folks that need to be in skilled nursing facilities or in rehab and we can’t get them to that next step.

Dan: So those patients become “boarders” — get stuck: they can’t get moved to the next step, but of course they can’t go home either.

Alex Janke: And so they wait in the ER and that creates crowding all around all the other patients.

Dan: The “boarders” fill up the ER beds. So everybody else piles up in the waiting room. Things get super-crowded. That sucks for those of us who show up as patients — a lot of us wait a super-long time. And that crowding — and the chaos that comes with it — creates burnout for people who work in ERs.

Alex Janke: The thing that burns you out is feeling like you’re not able to do a good job or you’re not in control of your working environment. And this is the reason. It is because it is crowded. Like an old lady comes in with belly pain. I can’t take care of that patient in the waiting room that I need that lady back in the department. I wanna get a CAT scan on that lady. I need some time with her. And it’s just, it’s, it’s dangerous and unpleasant all around.

Dan: Because you, because you don’t have space to see her. You don’t have a bed, you don’t have capacity to see her. And so she’s in danger.

Alex Janke: Absolutely. Without a doubt. And, you know, there’s a deep, there’s a deep literature on this, crowding impacts the quality of care along every possible dimension. It makes you more likely to screw up. I’m an ER doctor. My whole job is to not screw up. I’m like playing this game and the game is to not miss something really bad. And the faster you make me go with fewer resources, your ER doctor’s just a little more likely to screw up and not handle that correctly. I have gray hairs from a couple of cases.

Dan: He tells me about one of them. A woman who came in with a rash. When he finally examined her, twelve hours later, it turned out that rash was from flesh-eating bacteria. Those twelve hours meant that bacteria did a lot of damage. Alex says that woman spent a long time in the ICU, and took months to fully recover.

Alex Janke: I mean, those are the, you know, that’s one of the cases I know about, like how many patients have I been on shift and I don’t even know what happened,’cause there’s so much chaos going on that I don’t have insight into what might have missed or what we might not have done very well?

Dan: So the ER doesn’t work because it’s too crowded. And it’s crowded because of “boarders” — patients waiting for beds elsewhere. And in the next scene, we get Dr. Robbie’s perspective on WHY that’s happening. That’s when a hospital administrator, Gloria, shows up to give him a hard time. She says, WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT YOUR NUMBERS. Meaning, patient satisfaction numbers.

Gloria: Do you know how likely patients are to recommend this hospital? Robby: Um, this is an emergency department, not a Taco Bell. Gloria: 11%.

Robby: Well, if you want people to be happier, don’t make ’em wait for 12 hours.

Gloria: There’s a nursing shortage across the country.

Robby: Most of our patients are boarders who are waiting for a bed upstairs.

Gloria: We don’t have the beds.

Robby: That’s bullshit. The beds are up there. You just don’t want to hire the staff. You need to care for ‘em.

Dan: Alex has one little problem with this scene. He’s like, these conversations definitely happen, but not on shift, on the ER floor. But you know, OK it’s a TV show, and the whole premise is that we’re on the floor the whole time. And Alex has a second problem. Dr. Robby maybe does too good a job keeping his cool.

Alex Janke: You know, Dr. Robby is rushing from one dying patient to another, and someone shows up in a suit and says, you know, your patients aren’t very satisfied with your care. I think he handles it like an angel. If it were me, I think I would lose my job that day.

Dan: Otherwise, Alex is like: This is dead on.

Alex Janke: There’s so much going on here. This is wild. It’s so wild.

Dan: And he unpacks it. Yes, there’s a nursing shortage. Yes, there’s an actual shortage of hospital beds. And to a degree, these shortages are … business decisions.

Alex Janke: There’s some real truth, there’s a real hook to the idea that the emergency department waiting room and the emergency department beds as a place to keep folks waiting for a bed upstairs in the hospital — it is an optimization problem.

Dan: An optimization problem. That’s what Alex says people who study hospital administration have called this situation. The question is, what are you optimizing for? If you’re a hospital administrator, Alex says, you’re trying to optimize … your budget. You’re asking yourself: How do you get the most return for what you spend? You don’t do it by paying nurses to staff beds with no patients in them. Nobody’s paying you for empty beds.

Alex Janke: I mean, we want our hospital beds full. we’ve gotta pay these enormous costs for inputs, like, uh, nurses and, every single hour of nursing care that you pay for, you wanna make sure that, uh, it’s getting used. Every hospital bed day that you have staffed, you better fill up that bed.

Dan: So, now you’ve got a new equation to balance. Here’s how Alex describes the question:

Alex Janke: How do you maximize your patient bed days —that’s how you get paid — without ever having to turn away business?

Dan: OK, let’s unpack that: You want to maximize patient bed days. The number of beds that actually have patients in them, beds you’re getting paid for, on any given day. But you’ve limited the supply of beds upstairs. You don’t want to pay for something you might not be able to sell. And yet: You don’t want to turn away business.You’ve got a patient who needs a hospital room — a potential paying customer –you don’t wanna tell ‘em, hey we don’t have room for you on our cardiac ward. You gotta go somewhere else. So, how do you make room for patients — for customers — when there’s more demand?

Alex Janke: Well, one way to do that is to queue those patients, put them in a in a slot so that they’re ready to fill up that bed as soon as that bed becomes available. Where does that happen? The emergency department.

Dan: So this is why Alex is so enthusiastic about this scene: It dramatizes this whole analysis — and Dr. Robby’s perspective– the boarders who crowd up the ER and the waiting room: They’re the results of the hospital’s financial strategy. No wonder Dr. Robby’s mad.

Coming up: How doctors get caught in the processes that end up with awful bills for patients.

This episode of An Arm and a Leg is produced in partnership with KFF Health News. That’s a nonprofit newsroom covering health issues in America. Their reporters win all kinds of awards every year. We are honored to work with them.

We’re gonna skip ahead to episode six of The Pitt. No spoilers here. This scene stands alone, and it’s all business. Robby stops by a computer terminal where one of the newbies is charting– writing up her notes after seeing a patient. Listen for a key term right up top: Medical Decision Making. A little later we’ll hear Robby use its initials: MDM.

Dr. Robby: Four-year-old with a fever. Your medical decision making says otitis media.

Dr. Javadi: Yeah, she had an ear infection.

Robby: Did you also consider and rule out meningitis, mastoiditis, malignant otitis external?

Dr. Javadi: I did.

Dr. Robby: Then you should document your cognitive work in the MDM. Dr. Javadi: You want me to pad my chart?

Dr. Robby: No. I want you to show your work. Billing is the side effect of that.

Dan: “Billing is a ‘side effect’ of adding details” to the chart. When I watched that scene with Alex, he was like, Yup: charting is where our work turns into medical bills.

Alex Janke: So when we bill for care, we bill an insurer for care, we bill the chart, right?

Dan: The billing department translates the work described in the chart into 5-digit codes, and each one has a price tag. MDM, medical decision-making, contributes to codes for “evaluation and management” like 99281 or 99285.

Alex Janke: And if you bill for 99285, you get a whole bunch of money. And if you bill for, uh, 99281, then you get a little bit of money.

Dan: The only difference is that last number. It reflects a scale — 1 to 5 — how much work went into this visit. Was this straightforward? That’s a one. Was it high-level? Really complex? That could be a five. Researchers have found that “upcoding” — like billing a level four for something that’s really probably a two — is one reason why, as a country, we spend more on ER bills every year. I tell Alex: In one of the very first episodes of this podcast, we heard from a listener who had brought his son to the local ER — only place open at night — for what turned out to be …and ear infection. The hospital coded the visit a “4” out of

five. Pretty expensive. Our listener said, if that’s a four, what is it when you bring your leg in a bag? Alex was like, Yeah.

Alex Janke: There’s this fight between like physician groups on the one hand, and insurers on the other hand about like how hard our job is and how much they should pay us, and the only one who consistently loses in that fight is the patient.

Dan: Yeah. Well said. Well said.

Alex Janke: You’re absolutely right. It’s definitely true in emergency medicine. And you know, like I, I’ve written on this topic our patients are more medically complex than they have ever been. The complexity of the evaluation management that happens in the emergency department is higher than it has ever been. But that’s no excuse for, you know, leaving the patient with an absurd bill that’s out of proportion to what she did for them. This is one of the ways in which you’re like, put in all of these like little situations where like you’re in a lose-lose situation.

Dan: Lose-lose situation. Alex tells me a story. He was working in triage one day, and a guy came in with a bug bite.

Alex Janke: …and his buddy had convinced him that he might have like a really bad problem. He was like, this is a black widow spider bite. And it was a crazy day and I’m just like floating around at triage, slinging orders. And, he like stopped me in the hallway as he was like thinking about leaving. And he was like, do I really need to be seen for this? Do I really need to be seen for this? And I’m like, well, you have been seen. I am a doctor. And, and he walked out the door and I had this moment where I was like, do I go write a note on this guy? If I write a note, then we’ll bill him.

Dan: And Alex says he knew: That guy didn’t have insurance. Whatever that bill was, he could get stuck paying for it.

Alex Janke: I don’t know what that bill looks like. I don’t have insight into that. I don’t know how the place that I work at operates on that end. I’m almost never involved in it at all.

Dan: What’d you do?

Alex Janke: Nah, I didn’t write a note.