An Arm and a Leg: Winning a Two-Year Fight Over a Bogus Bill

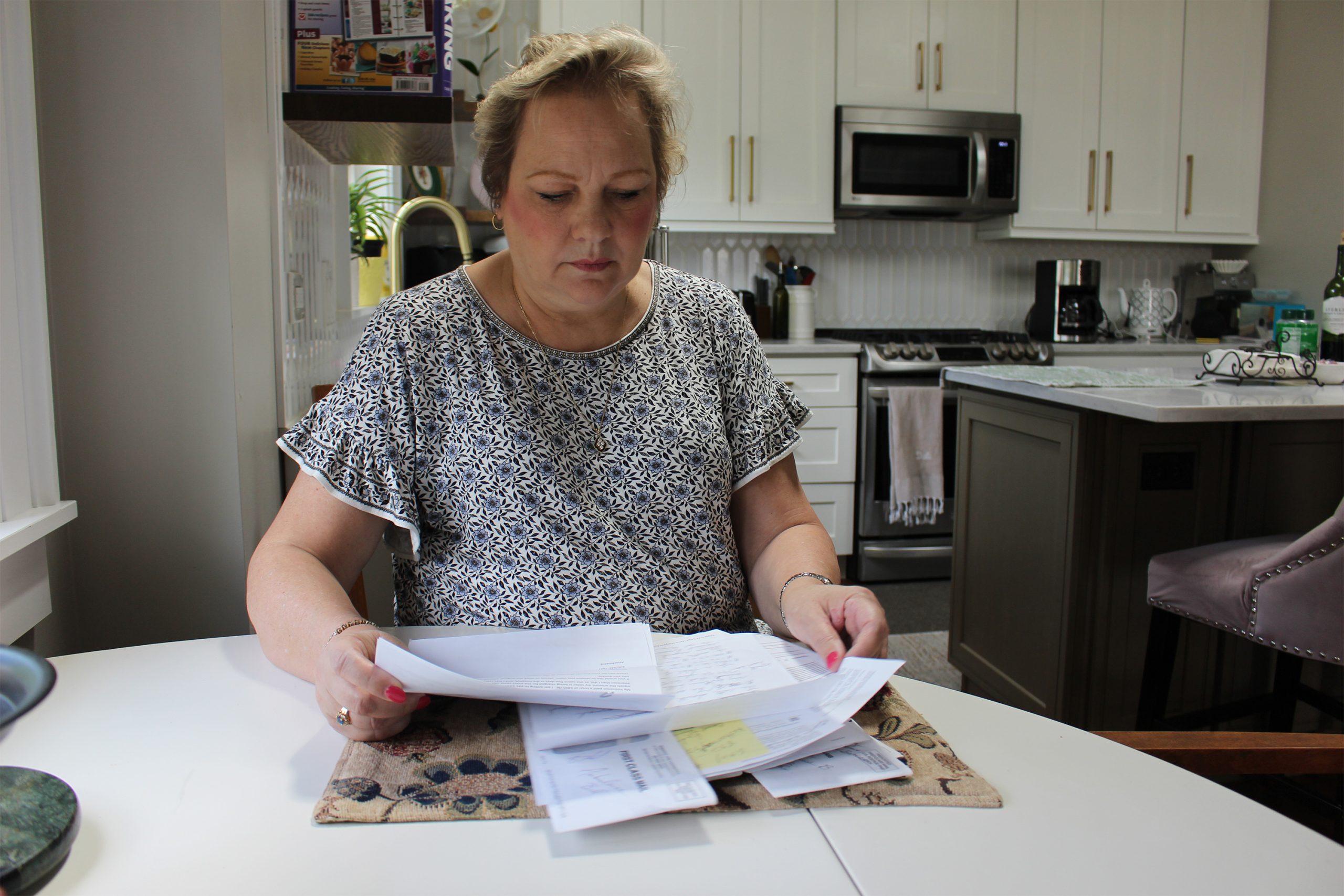

In July 2022, “An Arm and a Leg” listener Meagan experienced a bout of vertigo that landed her in the emergency room. For more than two years after, Meagan endured what felt like a never-ending series of communications with the hospital over a medical bill […]

Health Care

Medi-Cal Under Threat: Who’s Covered and What Could Be Cut?

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — Medi-Cal, California’s complex, $174.6 billion Medicaid program, provides health insurance for nearly 15 million residents with low incomes and disabilities. The state enrolls twice as many people as New York and more than three times as many as Texas — the two […]

Health Care

Quebec declares end to measles outbreak after no cases reported for 32 days

Health officials say an outbreak can be considered over if 32 days pass without a new reported infection.

Measles

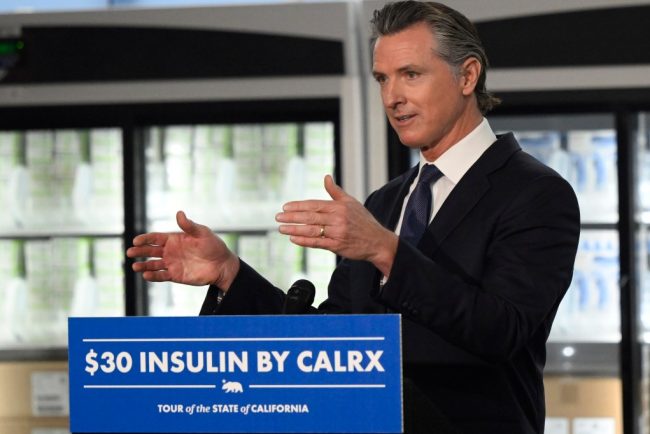

Top California Democrats Clash Over How To Rein In Drug Industry Middlemen

California Gov. Gavin Newsom and state legislators in Sacramento seem to agree: Prescription drug prices are too high. But lawmakers and the second-term governor are at odds over what to do about it, and a recent proposal could trigger one of the biggest health care […]

PharmaceuticalsCalifornia Gov. Gavin Newsom and state legislators in Sacramento seem to agree: Prescription drug prices are too high. But lawmakers and the second-term governor are at odds over what to do about it, and a recent proposal could trigger one of the biggest health care battles in Sacramento this year.

A California bill awaiting its first hearing would subject drug industry intermediaries known as pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs, to licensing by the state Department of Insurance. And it would require them to pass along 100% of the rebates they get from drug companies to the health plans and insurers that hire them to oversee prescription drug benefits.

But the proposal, which would impose some of the toughest PBM regulations in the nation, faces at least one major hurdle: Newsom. He vetoed a similar measure last year, unconvinced it would lower consumer costs. He signaled his intent to offer an alternative but has yet to reveal it.

Any fight over PBM reform promises to be a pricey one. Interest groups on both sides spent at least $7 million combined lobbying California lawmakers and the Newsom administration on health care last year, according to records filed with the secretary of state.

“This bill directly threatens the profitability of PBMs going forward,” said Ge Bai, a health policy professor at Johns Hopkins University who has tracked similar bills in other states. “These bills are really the result of an interindustry dog fight, and these are ridiculously fierce fights because PBMs control revenue for pharmacies, as well as for manufacturers.”

The country’s top three PBMs —CVS Caremark, affiliated with Aetna; UnitedHealth Group’s Optum Rx; and Express Scripts, owned by Cigna — control roughly 80% of prescriptions in the United States, according to the Federal Trade Commission. In theory, they leverage their buying power to extract steep discounts from drug manufacturers and pass savings along to insurance companies and employers who provide health coverage.

But as prescription drug prices continue to spiral and federal efforts to control them stall, state lawmakers are focusing on PBMs, which help insurers decide which drugs their plans cover and how much patients will pay out-of-pocket to get them. However, they have been stymied by the drug industry’s secretive ecosystem of rebates, reimbursements, and obscure fees, thwarting efforts to lower drug costs.

In addition to California, PBM proposals have been introduced this legislative session in Arkansas, Iowa, and at least 20 other states as of Feb. 10, according to the National Academy for State Health Policy. All 50 states and Washington, D.C., have some sort of PBM regulation on the books.

And although President Donald Trump has criticized PBMs and vowed to “knock out the middleman,” his recent actions undoing moves to lower prescription drug prices have left some health care experts skeptical that meaningful reform will come from Washington, D.C.

Meanwhile, state data shows California health plan drug costs have grown by more than 50% since 2017. California insurers spent 11% more on pharmaceuticals in 2023 than in 2022, with specialty and brand-name drugs driving the increase.

Both Newsom and bill author Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) have said PBMs play a role in high drug prices. While Wiener wants to ban some of their practices outright, Newsom has so far taken a more measured approach, calling for more disclosure and pointing to his plan for the state to manufacture its own generic drugs, which has yet to get off the ground.

In vetoing Wiener’s 2024 bill, which passed in a near-unanimous bipartisan vote, Newsom said he was unconvinced that licensing PBMs would improve affordability for patients and instead directed his administration to “propose a legislative approach” to gather more data from PBMs. In a statement, Newsom spokesperson Elana Ross noted that “Big Pharma backed the vetoed bill” and said the Democratic governor, in partnership with the legislature, will take action to address PBMs this year. She declined to elaborate.

In his January budget proposal, Newsom said his administration was “exploring approaches to increase transparency” in the entire drug supply chain, not just PBMs.

Industry representatives say they’re being unfairly targeted with transparency laws and regulations and blame pharmaceutical companies for setting high drug prices.

“The PBM is taking the risk on price variation, and it allows the client to have certainty on what they’re going to be paying,” said Bill Head, an assistant vice president of state affairs for the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, which represents PBMs. “We’re hired because it works. It saves money at the end of the day.”

He said PBMs pass on more than 95% of the rebates they receive from drugmakers — a number health policy researchers say is hard to verify.

Consumer advocates say drugmakers simply raise their prices to maintain profits and PBMs charge insurers far more for many medicines than pharmacies are paid to actually dispense them, a practice known as spread pricing.

A January report by the Federal Trade Commission found the three biggest PBMs appeared to steer the most profitable prescriptions away from competitors and to their affiliated pharmacies, which they reimbursed at markups exceeding 1,000% for some drugs, including some used to treat cancer, multiple sclerosis, and serious lung conditions. Over a six-year period, the analysis found, those PBMs and their affiliated pharmacies made roughly $8.7 billion in additional revenue by marking up prices on a sample of 51 specialty drugs.

Wiener’s latest bill, SB 41, would ban such markups, as well as spread pricing, and bar PBMs from receiving performance bonuses based on drug rebates. Similar provisions were stripped out of last year’s bill in the final days before its passage.

“These are practices that only PBMs are engaging in and they’re causing harm, reducing consumer choice, increasing drug costs, and it’s time to address them,” Wiener said. “I’m not going to let that idea just evaporate because of one veto.”

Clint Hopkins, who has co-owned Pucci’s Pharmacy in Sacramento since 2016, said he often deals with complaints from frustrated patients who don’t understand drug pricing schemes and restrictions set by pharmacy benefit managers.

He’s had to turn away customers whose drugs can cost him hundreds of dollars in losses each time they’re filled and says spread pricing is helping drive independent pharmacies out of business.

“I’m not asking to be paid more. I am asking to be paid fairly — at cost or above.”

Under current law, California requires PBMs to disclose some information about drug rebates, and other information, to its clients. That data is often labeled as proprietary to the companies, leaving an incomplete picture of the supply chain, said Maureen Hensley-Quinn, a senior program director at the National Academy for State Health Policy.

PBM representatives say pharmacies, insurers, and other actors in the supply chain should have to disclose information about their profits and practices, too.

“You want to look under the hood?” Head said. “We’re open to that, but let’s look under everybody’s hood.”

Bai said lawmakers are likely going after PBMs because insurers are one portion of the supply chain that they have the power to regulate. But she warned such legislation could cost consumers more if drugmakers and pharmacies remain unchecked. A better approach, Bai suggested, would be to bar PBMs entirely from managing benefits for generic drugs, one of their biggest revenue sources.

“In health care, there’s no saint and there’s no villain. Everybody’s trying to make money,” Bai said. “These fights will bring no benefit to patients unless we go to the root.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Long-Covid Patients Are Frustrated That Federal Research Hasn’t Found New Treatments

Erica Hayes, 40, has not felt healthy since November 2020 when she first fell ill with covid. Hayes is too sick to work, so she has spent much of the last four years sitting on her beige couch, often curled up under an electric blanket. […]

PharmaceuticalsErica Hayes, 40, has not felt healthy since November 2020 when she first fell ill with covid.

Hayes is too sick to work, so she has spent much of the last four years sitting on her beige couch, often curled up under an electric blanket.

“My blood flow now sucks, so my hands and my feet are freezing. Even if I’m sweating, my toes are cold,” said Hayes, who lives in Western Pennsylvania. She misses feeling well enough to play with her 9-year-old son or attend her 17-year-old son’s baseball games.

Along with claiming the lives of 1.2 million Americans, the covid-19 pandemic has been described as a mass disabling event. Hayes is one of millions of Americans who suffer from long covid. Depending on the patient, the condition can rob someone of energy, scramble the autonomic nervous system, or fog their memory, among many other symptoms.In addition to the brain fog and chronic fatigue, Hayes’ constellation of symptoms includes frequent hives and migraines. Also, her tongue is constantly swollen and dry.

“I’ve had multiple doctors look at it and tell me they don’t know what’s going on,” Hayes said about her tongue.

Estimates of prevalence range considerably, depending on how researchers define long covid in a given study, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts it at 17 million adults.

Despite long covid’s vast reach, the federal government’s investment in researching the disease — to the tune of $1.15 billion as of December — has so far failed to bring any new treatments to market.

This disappoints and angers the patient community, who say the National Institutes of Health should focus on ways to stop their suffering instead of simply trying to understand why they’re suffering.

“It’s unconscionable that more than four years since this began, we still don’t have one FDA-approved drug,” said Meighan Stone, executive director of the Long COVID Campaign, a patient-led advocacy organization. Stone was among several people with long covid who spoke at a workshop hosted by the NIH in September where patients, clinicians, and researchers discussed their priorities and frustrations around the agency’s approach to long-covid research.

Some doctors and researchers are also critical of the agency’s research initiative, called RECOVER, or Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery. Without clinical trials, physicians specializing in treating long covid must rely on hunches to guide their clinical decisions, said Ziyad Al-Aly, chief of research and development with the VA St Louis Healthcare System.

“What [RECOVER] lacks, really, is clarity of vision and clarity of purpose,” said Al-Aly, saying he agrees that the NIH has had enough time and money to produce more meaningful progress.

Now the NIH is starting to determine how to allocate an additional $662 million of funding for long-covid research, $300 million of which is earmarked for clinical trials. These funds will be allocated over the next four years.At the end of October, RECOVER issued a request for clinical trial ideas that look at potential therapies, including medications, saying its goal is “to work rapidly, collaboratively, and transparently to advance treatments for Long COVID.”

This turn suggests the NIH has begun to respond to patients. This has stirred cautious optimism among those who say that the agency’s approach to long covid has lacked urgency in the search for effective treatments.Stone calls this $300 million a down payment. She warns it’s going to take a lot more money to help people like Hayes regain some degree of health.“There really is a burden to make up this lost time now,” Stone said.

The NIH told KFF Health News and NPR via email that it recognizes the urgency in finding treatments. But to do that, there needs to be an understanding of the biological mechanisms that are making people sick, which is difficult to do with post-infectious conditions.

That’s why it has funded research into how long covid affects lung function, or trying to understand why only some people are afflicted with the condition.

Good Science Takes Time

In December 2020, Congress appropriated $1.15 billion for the NIH to launch RECOVER, raising hopes in the long-covid patient community.

Then-NIH Director Francis Collins explained that RECOVER’s goal was to better understand long covid as a disease and that clinical trials of potential treatments would come later.

According to RECOVER’s website, it has funded eight clinical trials to test the safety and effectiveness of an experimental treatment or intervention. Just one of those trials has published results.

On the other hand, RECOVER has supported more than 200 observational studies, such as research on how long covid affects pulmonary function and on which symptoms are most common. And the initiative has funded more than 40 pathobiology studies, which focus on the basic cellular and molecular mechanisms of long covid.

RECOVER’s website says this research has led to crucial insights on the risk factors for developing long covid and on understanding how the disease interacts with preexisting conditions.

It notes that observational studies are important in helping scientists to design and launch evidence-based clinical trials.

Good science takes time, said Leora Horwitz, the co-principal investigator for the RECOVER-Adult Observational Cohort at New York University. And long covid is an “exceedingly complicated” illness that appears to affect nearly every organ system, she said.

This makes it more difficult to study than many other diseases. Because long covid harms the body in so many ways, with widely variable symptoms, it’s harder to identify precise targets for treatment.

“I also will remind you that we’re only three, four years into this pandemic for most people,” Horwitz said. “We’ve been spending much more money than this, yearly, for 30, 40 years on other conditions.”

NYU received nearly $470 million of RECOVER funds in 2021, which the institution is using to spearhead the collection of data and biospecimens from up to 40,000 patients. Horwitz said nearly 30,000 are enrolled so far.

This vast repository, Horwitz said, supports ongoing observational research, allowing scientists to understand what is happening biologically to people who don’t recover after an initial infection — and that will help determine which clinical trials for treatments are worth undertaking.

“Simply trying treatments because they are available without any evidence about whether or why they may be effective reduces the likelihood of successful trials and may put patients at risk of harm,” she said.

Delayed Hopes or Incremental Progress?

The NIH told KFF Health News and NPR that patients and caregivers have been central to RECOVER from the beginning, “playing critical roles in designing studies and clinical trials, responding to surveys, serving on governance and publication groups, and guiding the initiative.”But the consensus from patient advocacy groups is that RECOVER should have done more to prioritize clinical trials from the outset. Patients also say RECOVER leadership ignored their priorities and experiences when determining which studies to fund.

RECOVER has scored some gains, said JD Davids, co-director of Long COVID Justice. This includes findings on differences in long covid between adults and kids.But Davids said the NIH shouldn’t have named the initiative “RECOVER,” since it wasn’t designed as a streamlined effort to develop treatments.

“The name’s a little cruel and misleading,” he said.

RECOVER’s initial allocation of $1.15 billion probably wasn’t enough to develop a new medication to treat long covid, said Ezekiel J. Emanuel, co-director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Healthcare Transformation Institute.

But, he said, the results of preliminary clinical trials could have spurred pharmaceutical companies to fund more studies on drug development and test how existing drugs influence a patient’s immune response.

Emanuel is one of the authors of a March 2022 covid roadmap report. He notes that RECOVER’s lack of focus on new treatments was a problem. “Only 15% of the budget is for clinical studies. That is a failure in itself — a failure of having the right priorities,” he told KFF Health News and NPR via email.

And though the NYU biobank has been impactful, Emanuel said there needs to be more focus on how existing drugs influence immune response.

He said some clinical trials that RECOVER has funded are “ridiculous,” because they’ve focused on symptom amelioration, for example to study the benefits of over-the-counter medication to improve sleep. Other studies looked at non-pharmacological interventions, such as exercise and “brain training” to help with cognitive fog.

People with long covid say this type of clinical research contributes to what many describe as the “gaslighting” they experience from doctors, who sometimes blame a patient’s symptoms on anxiety or depression, rather than acknowledging long covid as a real illness with a physiological basis.

“I’m just disgusted,” said long-covid patient Hayes. “You wouldn’t tell somebody with diabetes to breathe through it.”

Chimére L. Sweeney, director and founder of the Black Long Covid Experience, said she’s even taken breaks from seeking treatment after getting fed up with being told that her symptoms were due to her diet or mental health.

“You’re at the whim of somebody who may not even understand the spectrum of long covid,” Sweeney said.

Insurance Battles Over Experimental Treatments

Since there are still no long-covid treatments approved by the Food and Drug Administration, anything a physician prescribes is classified as either experimental — for unproven treatments — or an off-label use of a drug approved for other conditions. This means patients can struggle to get insurance to cover prescriptions.

Michael Brode, medical director for UT Health Austin’s Post-COVID-19 Program — said he writes many appeal letters. And some people pay for their own treatment.

For example, intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, low-dose naltrexone, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy are all promising treatments, he said.

For hyperbaric oxygen, two small, randomized controlled studies show improvements for the chronic fatigue and brain fog that often plague long-covid patients. The theory is that higher oxygen concentration and increased air pressure can help heal tissues that were damaged during a covid infection.

However, the out-of-pocket cost for a series of sessions in a hyperbaric chamber can run as much as $8,000, Brode said.

“Am I going to look a patient in the eye and say, ‘You need to spend that money for an unproven treatment’?” he said. “I don’t want to hype up a treatment that is still experimental. But I also don’t want to hide it.”

There’s a host of pharmaceuticals that have promising off-label uses for long covid, said microbiologist Amy Proal, president and chief scientific officer at the Massachusetts-based PolyBio Research Foundation. For instance, she’s collaborating on a clinical study that repurposes two HIV drugs to treat long covid.

Proal said research on treatments can move forward based on what’s already understood about the disease. For instance, she said that scientists have evidence — partly due to RECOVER research — that some patients continue to harbor small amounts of viral material after a covid infection. She has not received RECOVER funds but is researching antivirals.

But to vet a range of possible treatments for the millions suffering now — and to develop new drugs specifically targeting long covid — clinical trials are needed. And that requires money.

Hayes said she would definitely volunteer for an experimental drug trial. For now, though, “in order to not be absolutely miserable,” she said she focuses on what she can do, like having dinner with her family.At the same time, Hayes doesn’t want to spend the rest of her life on a beige couch.

RECOVER’s deadline to submit research proposals for potential long-covid treatments is Feb. 1.

This article is from a partnership that includes NPR and KFF Health News.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Health Care Is Newsom’s Biggest Unfinished Project. Trump Complicates That Task.

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — Six years after he entered office vowing to be California’s “health care governor,” Democrat Gavin Newsom has steered tens of billions in public funding to safety net services for the state’s neediest residents while engineering rules to make health care more accessible […]

PharmaceuticalsSACRAMENTO, Calif. — Six years after he entered office vowing to be California’s “health care governor,” Democrat Gavin Newsom has steered tens of billions in public funding to safety net services for the state’s neediest residents while engineering rules to make health care more accessible and affordable for all Californians.

More than a million California residents living in the U.S. without authorization now qualify for Medi-Cal, the state’s version of Medicaid, making California among the first states to cover low-income people regardless of their immigration status. The state is experimenting with Medicaid money to pay for social services such as housing and food assistance, especially for those living on the streets or with chronic diseases. And the state is forcing the health care industry to rein in soaring costs while imposing new rules on doctors, hospitals, and insurers to provide better-quality, more accessible care.

However, Newsom has so far failed to fully deliver on his most sweeping health care policies — and many changes are not yet visible to the public: Health care costs continue to rise, homelessness is worsening, and many Californians still struggle to get basic medical care.

Now, some of Newsom’s signature health initiatives, which could shape his profile on the national stage, are in peril as Donald Trump returns to the White House. According to national health policy experts, California stands to lose billions of dollars in health care funding should the Trump administration alter Medicaid programs as Republicans have indicated is likely. Such a move could force the state to dramatically slash benefits or eligibility.

And although allowing immigrants without legal status to enroll in free health care has been funded almost entirely with state money, it makes California a political target.

“That is fuel to feed the Republican MAGA argument that we are taking tax dollars from good Americans and providing health care to immigrants,” said Mark Peterson, a health care expert at UCLA, referring to the “Make America Great Again” movement.

Newsom declined an interview with KFF Health News. In a statement, he acknowledged that many of his initiatives are works in progress. But although he will attempt to work with Trump, the governor vowed to protect his health care agenda in his final two years in office.

“We are approaching the incoming administration with an open hand, not a closed fist,” Newsom said. “It is a top priority of my administration to ensure that quality health care is available and affordable for all Californians.”

Mark Ghaly, a former Health and Human Services secretary under Newsom, said transforming the way health care is paid for and delivered can be bumpy. “We didn’t do it perfectly,” Ghaly said. “Implementation is always messy in a state of 40 million people.”

Ahead of Trump’s Jan. 20 inauguration, Newsom has proposed allocating $25 million to challenge Trump on reproductive health care, disaster relief, and other services. His request is pending in the state’s Democratic-controlled legislature.

Here are the major initiatives that will shape Newsom’s health care legacy:

Medicaid

Potential federal cuts loom large in America’s most populous state. Of the whopping $261 billion California spends annually on health care and social services, nearly $116 billion flows from the federal government. Most of that goes to Medicaid, which covers more than 1 in 3 Californians. GOP leaders in Washington have floated ideas to kneecap Medicaid, which could slash benefits or cut enrollment.

In addition, California’s expansion of Medi-Cal to 1.5 million immigrants without legal status is projected to cost the state roughly $6.4 billion for the fiscal year ending June 30. Newsom suggested in early December that the state would continue to fund the immigrant health care expansion in the upcoming budget year but declined to say whether he would preserve the coverage in future years.

Advocacy groups are readying to defend those benefits should Trump target California over the issue. “We want to continue to protect access to care and not see a rollback,” said Amanda McAllister-Wallner, interim executive director of Health Access California.

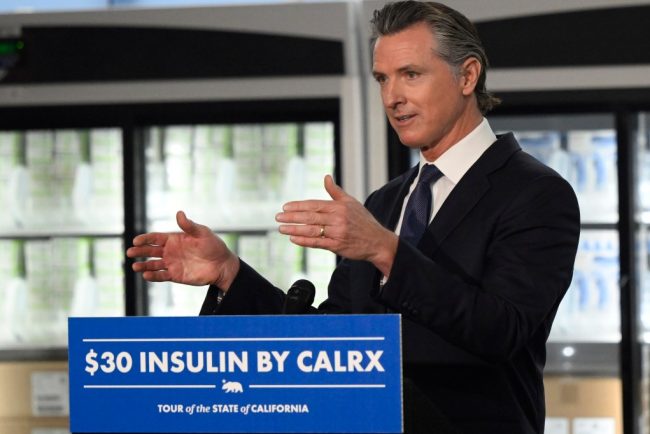

Generic Drugs

Citing the high cost of prescription drugs, Newsom in 2022 plowed $100 million into his plan to produce generic insulin for California and launch a state manufacturing plant to produce a range of generic drugs. Three years later, California has done neither. Newsom did, however, announce a deal in April to purchase in bulk the opioid reversal drug naloxone, which the state made available to schools, health clinics, and other institutions at a discount.

“It’s certainly disappointing that there isn’t much more progress on it,” said former state Sen. Richard Pan, who authored the original generic drug legislation.

On generic insulin, Newsom acknowledged “that it’s taken longer than we hoped to get insulin on the market, but we remain committed to delivering $30 insulin available to all who need it as soon as we can.”

Abortion

The governor helped lead the successful 2022 campaign to enshrine access to abortion in the state constitution. He signed laws to ensure abortions and miscarriages are not criminalized and to allow out-of-state doctors to perform abortions in California; built a stockpile of abortion medication when mifepristone faced a national ban; and set aside $20 million to help Californians who can’t afford abortion care to access it.

Newsom, who has made reproductive rights a central tenet of his political agenda, also funded ads and traversed the country attacking Trump and other Republicans in red states who have rolled back abortion access.

After Trump won the election, Newsom called a special legislative session to ready for potential legal battles with the federal government. He told KFF Health News the state is preparing “in every possible way to protect the rights guaranteed in California’s Constitution and ensure bodily autonomy for all those in our state.”

Rising Health Care Costs

In 2022, Newsom created the Office of Health Care Affordability to set limits on health care spending and impose penalties on industry payers and providers that fail to meet targets. By 2029, California will cap annual price increases for health insurers, doctors, and hospitals at 3%.

While Trump has voiced concern about the steady rise of health care costs nationally — and the quality of health care Americans are receiving — his ideas have focused on deregulation and replacing the Affordable Care Act, which experts say could cost millions their health coverage and increase patient health care spending. California could potentially lose federal subsidies that have helped offset insurance premiums for most of the roughly 1.8 million people who buy their health coverage from Covered California, the state’s ACA marketplace, which would increase patient out-of-pocket costs.

The state could use money it raises from its own health insurance penalty on the uninsured, which Newsom adopted after the Obamacare individual mandate was zeroed out by Congress in 2017. Those state revenues are projected to be $298 million this fiscal year, according to the state Department of Finance. That’s a fraction of the federal health insurance subsidies California receives — roughly $1.7 billion annually.

Health and Homelessness

Under Newsom, California has spent unprecedented public money on tackling homelessness, yet the crisis has worsened under his watch.

From 2019, when Newsom took office, to 2023, homelessness jumped 20% to more than 181,000, despite his funneling more than $20 billion into trying to get people off the streets, including converting hotels and motels into homeless housing. He has also plowed roughly $12 billion into CalAIM, an experimental effort to infuse Medi-Cal with social services, including rental and eviction assistance.

A state audit last year found the state isn’t doing a good job of tracking the effectiveness of taxpayer money. CalAIM isn’t serving as many Californians as expected and patients face difficulty receiving new benefits from health insurers.

“The homelessness crisis on our streets is unacceptable,” Newsom acknowledged. “But we are starting to see progress.”

Experts expect the Trump administration to reverse liberal policies that have allowed Medicaid money to be used for health care experiments through waivers encouraged by the Biden administration. Notably, Trump has attacked Newsom for his handling of the homelessness crisis and has vowed to more forcefully move people off the streets. California’s CalAIM waiver ends at the end of 2026.

Instead of expanding housing and food assistance, for instance, the state could instead see federal moves to end CalAIM benefits and make Medicaid more restrictive.

Mental Health and Substance Use

Newsom has launched the most extensive overhaul of California’s behavioral health system in decades, directing billions in state funding toward a new network of treatment facilities and prevention programs.

Two of his most controversial signature initiatives, Proposition 1 and CARE Court, infuse money into treatment and housing for Californians with behavioral health conditions, especially homeless people living in crisis. And CARE Court allows judges to compel treatment for those suffering from debilitating mental illness and substance use.

Both have been hamstrung by funding challenges, rely on counties for implementation, and could take years to produce noticeable results. Whereas Newsom has sought to expand community-based treatment, Trump has promised a return to institutionalization and suggested homeless people and those with severe behavioral health conditions be moved to “large parcels of inexpensive land.”

Newsom said he hopes his “innovative” approaches will transform behavioral health care with “a laser focus on people with the most serious illness and substance use disorders.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

La salud, un proyecto inconcluso del gobernador de California

SACRAMENTO, California.— Seis años después de asumir el cargo prometiendo ser el “gobernador de la salud” de California, el demócrata Gavin Newsom ha destinado decenas de miles de millones de dólares de fondos públicos a servicios de la red de seguridad para los residentes más […]

PharmaceuticalsSACRAMENTO, California.— Seis años después de asumir el cargo prometiendo ser el “gobernador de la salud” de California, el demócrata Gavin Newsom ha destinado decenas de miles de millones de dólares de fondos públicos a servicios de la red de seguridad para los residentes más necesitados del estado, mientras diseña reglas para hacer que la atención médica sea más accesible y asequible para todos los californianos.

Más de un millón de residentes de California que viven en Estados Unidos sin papeles ahora califican para Medi-Cal, la versión estatal de Medicaid: ha sido uno de los primeros en cubrir a personas de bajos ingresos independientemente de su estatus migratorio.

El estado también está experimentando con fondos de Medicaid para pagar servicios sociales como asistencia para vivienda y alimentos, especialmente para aquellos que viven en las calles o tienen enfermedades crónicas. Además, está obligando a la industria de la salud a controlar los costos desbordantes mientras impone nuevas reglas a médicos, hospitales y aseguradoras para ofrecer una atención de mejor calidad y más accesible.

Sin embargo, hasta ahora, Newsom no ha logrado cumplir por completo con sus políticas de salud más ambiciosas, y muchos cambios aún no son visibles para el público: los costos de la salud siguen aumentando, la escasez de vivienda está empeorando y muchos californianos todavía luchan por obtener atención médica básica.

Ahora, algunas de las iniciativas emblemáticas de Newsom en materia de salud, que podrían definir su perfil en el escenario nacional, están en peligro con el regreso de Donald Trump a la Casa Blanca.

Según expertos en políticas sanitarias, California podría perder miles de millones de dólares en financiamiento para la atención médica si la nueva administración Trump altera los programas de Medicaid, algo que los republicanos han dicho que es probable. Tal movimiento podría obligar al estado a recortar drásticamente beneficios, e incluso la elegibilidad.

Y aunque la inscripción para que inmigrantes indocumentados obtengan atención médica gratuita se ha financiado casi completamente con dinero estatal, esto convierte a California en un blanco político.

“Eso es combustible para alimentar el argumento de la republicana MAGA de que estamos tomando dólares de impuestos de buenos estadounidenses y proporcionando atención médica a los inmigrantes”, dijo Mark Peterson, experto en atención médica de UCLA, en referencia al movimiento “Make America Great Again”.

Newsom rechazó una entrevista con KFF Health News. En un comunicado, reconoció que muchas de sus iniciativas todavía están en proceso de implementarse. Pero, aunque intentará trabajar con Trump, el gobernador prometió proteger su agenda de atención médica en sus dos últimos años en el cargo.

“Nos estamos acercando a la administración entrante con una mano abierta, no con un puño cerrado”, dijo Newsom. “Es una prioridad principal de mi administración asegurar que la atención médica de calidad esté disponible y sea asequible para todos los californianos”.

Mark Ghaly, ex secretario de Salud y Servicios Humanos bajo Newsom, dijo que transformar la forma en que se paga y ofrece la atención médica puede ser complicado. “No lo hicimos perfectamente”, dijo Ghaly. “La implementación siempre es complicada en un estado de 40 millones de personas”.

Antes de la inauguración de Trump el 20 de enero, Newsom propuso asignar $25 millones para desafiar a Trump en atención reproductiva, ayuda para desastres y otros servicios. Su solicitud está pendiente en la Legislatura estatal controlada por demócratas.

Estas son las principales iniciativas que conformarán el legado de Newsom en salud:

Medicaid

Se avecinan posibles recortes federales en el estado más poblado de Estados Unidos. De los asombrosos $261 mil millones que California gasta anualmente en atención médica y servicios sociales, casi $116 mil millones provienen del gobierno federal. La mayor parte de eso va a Medicaid, que cubre a más de 1 de cada tres californianos. Líderes republicanos en Washington han planteado ideas para debilitar el programa, lo que podría reducir beneficios o disminuir la inscripción.

Además, la expansión de Medi-Cal en California para 1.5 millones de inmigrantes sin papeles se proyecta que costará al estado aproximadamente $6.4 mil millones para el año fiscal que termina el 30 de junio.

A principios de diciembre, Newsom sugirió que el estado continuaría financiando la expansión de atención médica para inmigrantes en el próximo año fiscal, pero no quiso decir si mantendría la cobertura en años futuros.

Grupos de defensa están listos para proteger estos beneficios si Trump hace de California su blanco. “Queremos continuar protegiendo el acceso a la atención y no ver un retroceso”, dijo Amanda McAllister-Wallner, directora ejecutiva interina de Health Access California.

Medicamentos genéricos

Citando el alto costo de los medicamentos recetados, en 2022 Newsom destinó $100 millones a su plan para producir insulina genérica para California y lanzar una planta estatal de fabricación para producir una gama de medicamentos genéricos.

Tres años después, California no ha logrado ninguno de los dos. Sin embargo, en abril Newsom anunció un acuerdo para comprar al por mayor naloxona, el medicamento para revertir las sobredosis de opioides, que el estado puso a disposición de escuelas, clínicas de salud y otras instituciones a un precio reducido.

“Es ciertamente decepcionante que no haya mucho más progreso”, dijo el ex senador estatal Richard Pan, quien redactó la legislación original de medicamentos genéricos.

Sobre la insulina genérica, Newsom reconoció “que ha tomado más tiempo del que esperábamos llevar insulina al mercado, pero seguimos comprometidos a ofrecer insulina a $30 disponible para todos los que la necesiten lo antes posible”.

Aborto

El gobernador ayudó a liderar la exitosa campaña de 2022 para incluir el acceso al aborto en la constitución estatal. Firmó leyes para garantizar que los abortos, espontáneos o no, no fueran criminalizados, para permitir que médicos de otros estados realicen abortos en California, almacenar medicamentos abortivos cuando mifepristona enfrentó una prohibición nacional, y destinó $20 millones para ayudar a los californianos que no pueden pagar el cuidado del aborto.

Newsom, quien ha hecho de los derechos reproductivos un pilar central de su agenda política, también financió anuncios y recorrió el país atacando a Trump y a otros republicanos en estados conservadores que han restringido el acceso al aborto.

Después de la victoria electoral de Trump, Newsom convocó a una sesión legislativa especial para prepararse para posibles batallas legales con el gobierno federal. Dijo a KFF Health News que el estado se está preparando “de todas las maneras posibles para proteger los derechos garantizados en la constitución de California y asegurar la autonomía para todos los que están en nuestro estado”.

Costos crecientes de la atención médica

En 2022, Newsom creó la Office of Health Care Affordability para establecer límites al gasto en salud e imponer sanciones a las aseguradoras y proveedores de atención médica que no cumplieran con los objetivos. Para 2029, California limitará los aumentos anuales de precios para aseguradoras, médicos y hospitales al 3%.

Si bien Trump ha expresado preocupación por el aumento constante de los costos de la atención médica a nivel nacional y la calidad de la atención, sus ideas se han centrado en la desregulación y en reemplazar la Ley de Cuidado de Salud a Bajo Precio (ACA), lo que, según expertos, podría costar a millones su cobertura de salud y aumentar los gastos de los pacientes.

California podría perder subsidios federales que han ayudado a reducir las primas de seguros para la mayoría de los aproximadamente 1.8 millones de personas que compran su cobertura de salud a través de Covered California, el mercado estatal de ACA, lo que aumentaría los gastos de bolsillo de los pacientes.

El estado podría usar el dinero que recauda de sus propias multas por no tener seguro de salud, adoptada por Newsom después que el Congreso eliminara el mandato individual de Obamacare en 2017. Según el Departamento de Finanzas del estado, esos ingresos estatales están proyectados en $298 millones para este año fiscal. Eso es una fracción de los aproximadamente $1.7 mil millones anuales en subsidios federales para seguros de salud que recibe California.

Salud y falta de vivienda

Bajo el liderazgo de Newsom, California ha gastado cantidades sin precedentes de dinero público para abordar la crisis de personas sin hogar, pero la situación ha empeorado bajo su mandato.

Desde 2019, cuando Newsom asumió el cargo, hasta 2023, la falta de vivienda aumentó un 20%: más de 181,000 personas no tienen techo, a pesar que el estado destinó más de $20 mil millones para tratar de sacar a las personas de las calles, incluido un programa para convertir hoteles y moteles en viviendas para los sin hogar.

Además, se han invertido aproximadamente $12 mil millones en CalAIM, un esfuerzo experimental para integrar servicios sociales en Medi-Cal, como asistencia para alquilar y para prevenir desalojos.

El año pasado, una auditoría estatal encontró que el estado no estaba haciendo un buen trabajo en el seguimiento de la efectividad del dinero de los contribuyentes. CalAIM no está sirviendo a tantos californianos como se esperaba, y los pacientes enfrentan dificultades para recibir los nuevos beneficios de los aseguradores de salud.

“La crisis de personas sin hogar en nuestras calles es inaceptable”, reconoció Newsom. “Pero estamos comenzando a ver avances”.

Se espera que la administración Trump revierta las políticas liberales que han permitido el uso de dinero de Medicaid para experimentos de atención médica a través de exenciones alentadas por la administración Biden.

Notablemente, Trump ha criticado a Newsom por su manejo de la crisis de personas sin hogar y ha prometido sacar a las personas de las calles con más fuerza. La exención de CalAIM en California termina a finales de 2026.

Por ejemplo, en lugar de expandir la asistencia de vivienda y alimentos, el estado podría enfrentarse a movimientos federales para terminar los beneficios de CalAIM y hacer que Medicaid sea más restrictivo.

Salud mental y adicciones

Newsom ha lanzado la reforma más extensa del sistema de salud conductual de California en décadas, destinando miles de millones en fondos estatales a una nueva red de instalaciones de tratamiento y programas de prevención.

Dos de sus iniciativas emblemáticas más controvertidas, la Proposición 1 y CARE Court, inyectan dinero en el tratamiento y la vivienda para californianos con afecciones de salud conductual, especialmente personas sin hogar que viven en crisis. CARE Court permite a los jueces ordenar tratamiento para quienes sufren enfermedades mentales debilitantes y trastornos por adicciones.

Ambas iniciativas han enfrentado desafíos de financiamiento, dependen de los condados para su implementación y podrían tardar años en producir resultados visibles.

Mientras que Newsom ha buscado expandir el tratamiento en las comunidades, Trump ha sugerido un regreso a la institucionalización y propuso trasladar a personas sin hogar y a aquellos con graves afecciones de salud conductual a “grandes extensiones de tierra económica”.

Newsom dijo que espera que sus enfoques “innovadores” transformen la atención de salud conductual con “un enfoque en las personas con enfermedades más graves y adicciones”.

Esta historia fue producida por Kaiser Health News, que publica California Healthline, un servicio editorialmente independiente de la California Health Care Foundation.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

‘Bill of the Month’: The Series That Dissects and Slashes Medical Bills

Over 6½ years ago, KFF Health News and NPR kicked off “Bill of the Month,” a crowdsourced investigation highlighting the impact of medical bills on patients. The goal was to understand how the U.S. health care system generates outsize bills and to empower patients with […]

PharmaceuticalsOver 6½ years ago, KFF Health News and NPR kicked off “Bill of the Month,” a crowdsourced investigation highlighting the impact of medical bills on patients.

The goal was to understand how the U.S. health care system generates outsize bills and to empower patients with strategies to avoid them. We asked readers and listeners to submit their bills — and they kept coming. “Bill of the Month” has received nearly 10,000 submissions, each a picture of a health system’s dysfunction and the financial burden it places on the patients.

Since 2018, we have analyzed bills totaling almost $6.3 million — including nearly $2.8 million that patients were expected to pay out-of-pocket.

Cited at statehouses and the U.S. Capitol, the series has led to changes in health policy. Two patients featured by “Bill of the Month” were invited to the White House in 2019 to discuss their surprise bills: Elizabeth Moreno’s $18,000 urine test and Drew Calver’s $109,000 heart attack. In 2020, Congress passed the federal No Surprises Act, shielding patients from most out-of-network bills in emergencies, among other protections.

Last year, the Biden administration announced plans to lower health costs that included targeting a loophole that allowed health providers to evade the surprise-billing law — a problem first identified by “Bill of the Month.”

Many patients submitted high prescription drug bills. In treatment for prostate cancer, Paul Hinds was billed nearly $74,000 for two shots of an old drug called Lupron, which can cost just a couple of hundred dollars overseas.

Now, the federal government has identified Lupron as one of the medicines that has seen its price rise faster than inflation — meaning its manufacturer owes rebates to Medicare under President Joe Biden’s 2022 Inflation Reduction Act.

The law also authorized the Biden administration to begin negotiating the price of specified drugs for Medicare patients, who now benefit from a cap on the price of insulin.

“Bill of the Month” has helped many patients and readers get their medical bills reduced or forgiven. Roughly 1 in 3 bills were resolved for patients by the time their features were published.

Bisi Bennett was charged $550,124 after her son was in a neonatal intensive care unit for nearly two months — despite having insurance. In a recent interview, nearly three years after her bill was investigated by “Bill of the Month,” she said she initially thought resolving the bill would be simple.

“Nine months later, 10 months later, I was still fighting with them,” she said. “I really did feel like it kind of robbed me a little bit of the joy of the first months of motherhood.”

Once a reporter started making calls, Bennett said, “they somehow miraculously figured out how to bill the right parties and get it sorted out.”

But relief from individual bills is one thing; patients say bigger solutions are needed for what ails our health system. “This isn’t just about my bill,” Calver said in 2018, when his nearly $109,000 bill was reduced to $332 after being investigated by “Bill of the Month.” “I don’t feel any consumer should have to go through this.”

The Takeaways

The “Bill of the Month” mantra is: If the bill is unexpected or seems off, don’t write the check. Each installment offered directions to navigate health care’s rough financial waters.

Some bills memorably illustrated the absurdity of a system that turns ordinary mishaps into extraordinary revenues. After 3-year-old Lucy Branson got a Polly Pocket doll shoe stuck up her nose, her family was charged about $2,659 for an ER doctor to fish it out with forceps — essentially a long pair of tweezers.

Here are some of the most important lessons — and some patients who offered their experiences to teach them:

- Before scheduling services, ask if a provider is in-network — then read waiting-room forms closely. Feeling sick and unable to rule out covid-19, Elyse Greenblatt booked a telemedicine appointment. But her in-network doctor’s office paired her with an out-of-network doctor — and said she’d signed a consent form. Her insurer declined to pay a penny of the $660 bill.

- Ask for an itemized bill, and question charges that don’t make sense. Eloise Reynolds paid her husband’s final hospital bill after he died from colon cancer. A year later, she received a second bill for his stay. Reynolds requested an itemized bill — and using a yardstick as a straight edge, went line by line to sort out why the hospital said she owed nearly $1,100 more. The balance was eventually deemed a “clerical error” and eliminated.

- Beware ambulances. The landmark No Surprises Act protected patients from many surprise bills in emergencies, but it does not apply to ground ambulances, which are unlikely to contract with insurance and thus might bill willy-nilly. When Peggy Dula was in a car accident, she was picked up by a fire department ambulance that was out-of-network. Though she wasn’t terribly hurt, her ride generated a $3,606 charge, and — after her insurance paid an amount it deemed “reasonable and customary” — she owed around $2,711.

- Location Matters, Part 1: Any intervention or test done in a hospital is likely to cost more than elsewhere. After her first prenatal checkup, Reesha Ahmed had her blood drawn for routine tests by a hospital lab. The bill: $9,520. Ahmed, who had a miscarriage, owed $2,390.

- Location Matters, Part 2: Doctors’ offices can be reclassified as hospital facilities if they’re purchased by a hospital system — and then add on hospital facility fees. Kyunghee Lee, a retired seamstress, went to her doctor for regular injections to treat arthritis for a copay of about $30. Then the office moved one floor up — and her bill changed: Newly designated as taking place in “a hospital-based setting,” one visit was billed at $1,394, including a facility fee listed as “operating room services.” Lee owed about $355.

- Location Matters, Part 3: Some free-standing emergency rooms may look like urgent care centers but come with ER charges. Tieqiao Zhang believed he was visiting urgent care when he sought treatment for a kidney stone at a facility called an “urgent care emergency center.” He went there twice and, both times, was given IV hydration and painkillers, then sent home. The visits yielded a bill of $19,543, including a $500 copay for each visit to what was actually a free-standing ER.

- Sometimes it can pay to pay cash. Dani Yuengling needed a breast biopsy after a concerning mammogram. The hospital’s online price calculator listed a price of about $1,400 for those without insurance. So she was shocked to see her own bill, paid using insurance, was almost $18,000, of which she owed more than $5,000 under the terms of her high-deductible plan.

The Resolution

Some bills signal that there’s more to be done to tame a health care industry in which seemingly everything can be billable. Mansi Bhatt took her toddler, Martand, to the emergency room for a burn on his hand, but after a long wait, they left before being seen by a doctor. Just checking in yielded an $859 bill, which the family had to pay since they hadn’t met their deductible.

Even new protections, such as those for air-ambulance bills, have problems. Amari Vaca was 3 months old and recovering from open-heart surgery when he contracted the life-threatening virus RSV, or respiratory syncytial virus. When doctors said he needed specialized care, he was transferred by air ambulance to a different hospital. The family’s insurer denied the claim, determining the flight wasn’t medically necessary, and the hospital declined to file an appeal. Vaca’s mother, Sara England, notified KFF Health News in October that their final appeal was denied. They owe $97,000.

And old bills die hard. When “Bill of the Month” reconnected with Phil Gaimon this fall, he said he had called his providers recently to check his outstanding balance — and learned it was, at last, zero.

Gaimon was competing to qualify for the Olympics when he was in a bicycle crash and wound up with bills topping $200,000. “I think I was home from the hospital in 10 days, riding my bike again in a month,” he said in an interview. “And then the bills … three years.”

While our “Bill of the Month” partnership with NPR is sunsetting, the “Bill of the Month” series will continue as KFF Health News investigates your medical bills. Keep them coming! And watch for future stories in The Washington Post’s Well+Being.

Elisabeth Rosenthal is a senior contributing editor for KFF Health News and the creator of “Bill of the Month.”

Emily Siner reported the audio story.

Henry Larweh and Molly Castle Work of KFF Health News contributed reporting for this article.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

New Alberta COVID data highlights value of getting newly formulated vaccine once available: expert

The latest data published on the Alberta respiratory virus dashboard show that between August 2023 and August 2024, 732 deaths in Alberta were attributed to COVID-19.

CoronavirusThe latest data published on the Alberta respiratory virus dashboard show that between August 2023 and August 2024, 732 deaths in Alberta were attributed to COVID-19.

Your ‘summer cold’ could likely be COVID-19, doctors say amid surge

Gayle Robin was surprised when her sister in California told her in early July she had tested positive for COVID-19, which is rising in Canada, health experts say.

CoronavirusGayle Robin was surprised when her sister in California told her in early July she had tested positive for COVID-19, which is rising in Canada, health experts say.

Not too late to get flu, COVID-19 shots before Christmas: experts

With a record number of influenza cases recorded in Alberta, experts are recommending people get their flu shots.

CoronavirusWith a record number of influenza cases recorded in Alberta, experts are recommending people get their flu shots.

Quebec health-care establishments argue against allowing COVID-19 class action

If the case is allowed to go ahead, it would cover all residents of long-term care homes where COVID-19 outbreaks occurred during the first two waves of the pandemic.

CoronavirusIf the case is allowed to go ahead, it would cover all residents of long-term care homes where COVID-19 outbreaks occurred during the first two waves of the pandemic.

Manitoba’s two major political parties say they would not repeat COVID-19 lockdowns

Manitobans were never locked in their homes. But at the height of the pandemic, there were temporary restrictions on having visitors.

CoronavirusManitobans were never locked in their homes. But at the height of the pandemic, there were temporary restrictions on having visitors.