El costo humano de los recortes de Trump a los programas de tratamiento de adicciones

Cuando la administración Trump recortó a finales de marzo más de $11.000 millones en fondos estatales destinados a la era de covid-19, los programas de recuperación de adicciones sufrieron pérdidas rápidas. Una organización de Indiana que emplea a personas en recuperación para ayudar a compañeros […]

Health Care

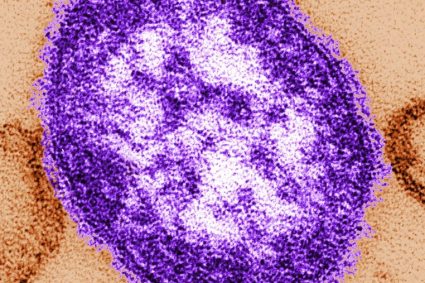

Manitoba measles cases climb as vaccination rates fall

Driedger says public health messaging that is specific to each type of vaccine is more effective in helping vaccine-hesitant people make a decision.

Measles

Ontario Liberals call for urgent action to tackle ‘staggering’ measles outbreak

The latest data from Public Health Ontario shows the province has recorded 1,020 new measles since an outbreak began last October.

Measles

Confirmed measles case in Calgary area prompts AHS public alert

The alert was issued Friday evening. A representative with AHS tells Global News that currently one person has been confirmed with a case of measles.

MeaslesThe alert was issued Friday evening. A representative with AHS tells Global News that currently one person has been confirmed with a case of measles.

‘Dead Zones’ Where Internet and Health Care Lag

Congressional Republicans and President Donald Trump’s administration are taking aim at a $42 billion infrastructure program launched in 2021 to bring high-speed internet to all Americans. Republican critics say the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program from former President Joe Biden’s bipartisan infrastructure law has […]

Rural HealthCongressional Republicans and President Donald Trump’s administration are taking aim at a $42 billion infrastructure program launched in 2021 to bring high-speed internet to all Americans.

Republican critics say the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program from former President Joe Biden’s bipartisan infrastructure law has been slow to get “shovels into the ground.” U.S. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick last week said the program had too many “woke mandates” and announced a “rigorous review.”

Democrats, though, say a pause in the program will only further delay construction. More delays mean America’s least connected, least healthy counties will continue to wait for the high-speed internet needed to use telehealth, which is one of the few bipartisan solutions for rural health care shortages.

Here’s what our reporting found: Lots of people are waiting for high-speed internet. And that’s hurting them.

My colleague Holly K. Hacker mapped federal broadband data and, working with researchers from George Washington University, found that nearly 3 million people live in more than 200 mostly rural counties where in-person care is extremely limited and telehealth is largely out of reach.

Those “dead zone” counties are concentrated in regions often pinpointed for having inadequate services: Appalachia, the rural South, and the remote West. The analysis also showed that people who live in these counties tend to be sicker and die earlier than most other Americans.

Back in September 2020, I wrote an article about Trump’s first administration announcing a sweeping plan to transform health care in rural America. The word “telehealth” appeared in the plan more than 90 times. I wanted to understand whether telehealth could really help rural places, like where I grew up in Kansas.

In the coming months, we’ll take you to some dead zone counties to answer that question. The first feature, which published and aired this week, follows Barbara Williams, who lives in Greene County, Alabama, and is managing diabetes without a dependable internet connection.

That can mean “a huge difference in diabetes outcomes,” said Nestoras Mathioudakis, an endocrinologist and the co-medical director of Johns Hopkins Medicine Diabetes & Education Program.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

COVID-19 likely leaked from Wuhan lab, reports say Germany’s spies assessed

Germany’s spy agency put at 80 to 90 per cent the likelihood that the coronavirus behind COVID-19 was accidentally released from a Wuhan lab, two German newspapers reported.

CoronavirusGermany’s spy agency put at 80 to 90 per cent the likelihood that the coronavirus behind COVID-19 was accidentally released from a Wuhan lab, two German newspapers reported.

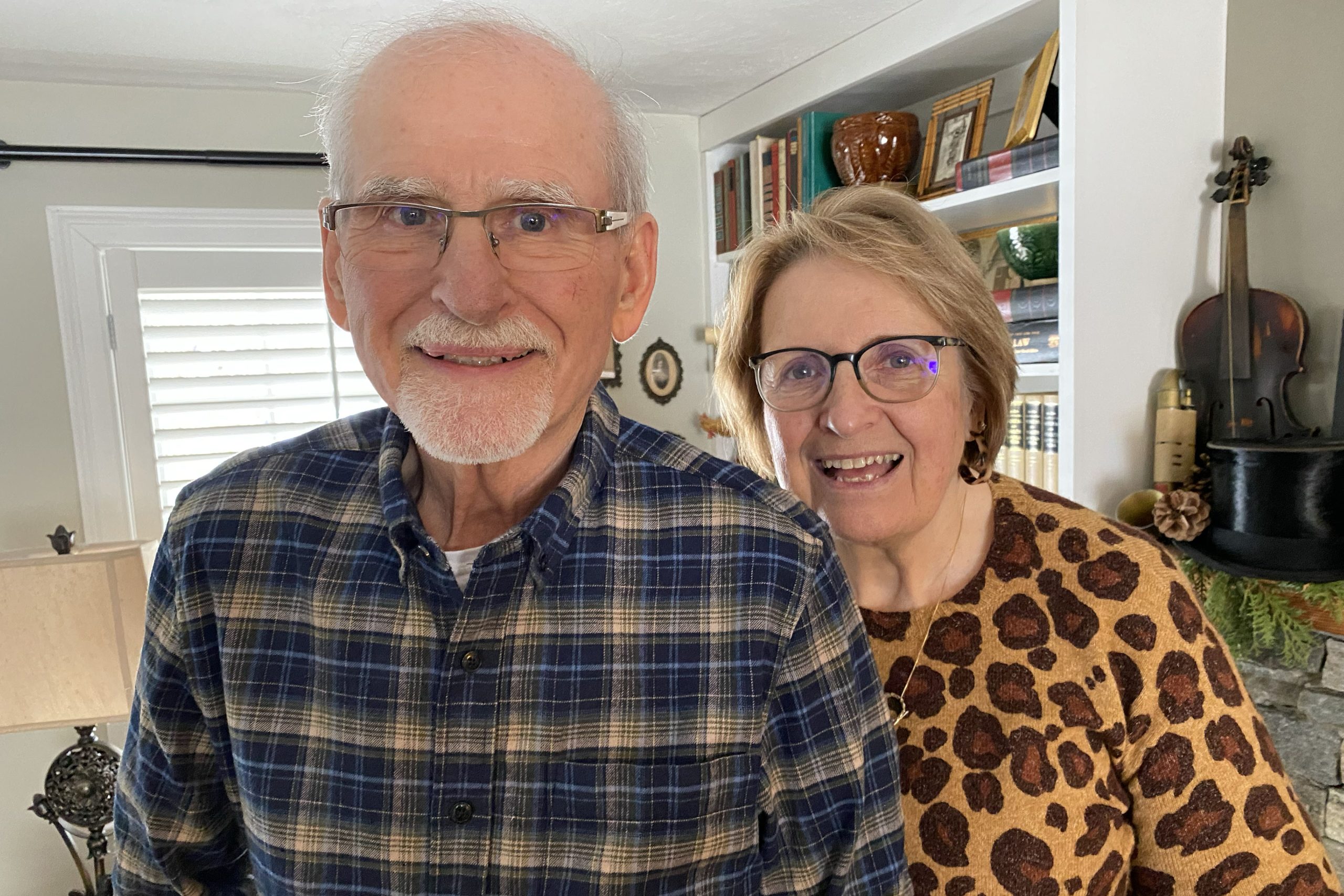

Sent Home To Heal, Patients Avoid Wait for Rehab Home Beds

After a patch of ice sent Marc Durocher hurtling to the ground, and doctors at UMass Memorial Medical Center repaired the broken hip that resulted, the 75-year-old electrician found himself at a crossroads. He didn’t need to be in the hospital any longer. But he […]

Rural HealthAfter a patch of ice sent Marc Durocher hurtling to the ground, and doctors at UMass Memorial Medical Center repaired the broken hip that resulted, the 75-year-old electrician found himself at a crossroads.

He didn’t need to be in the hospital any longer. But he was still in pain, unsteady on his feet, unready for independence.

Patients nationwide often stall at this intersection, stuck in the hospital for days or weeks because nursing homes and physical rehabilitation facilities are full. Yet when Durocher was ready for discharge in late January, a clinician came by with a surprising path forward: Want to go home?

Specifically, he was invited to join a research study at UMass Chan Medical School in Worcester, Massachusetts, testing the concept of “SNF at home” or “subacute at home,” in which services typically provided at a skilled nursing facility are instead offered in the home, with visits from caregivers and remote monitoring technology.

Durocher hesitated, worried he might not get the care he needed, but he and his wife, Jeanne, ultimately decided to try it. What could be better than recovering at his home in Auburn with his dog, Buddy?

Such rehab at home is underway in various parts of the country — including New York, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin — as a solution to a shortage of nursing home and rehab beds for patients too sick to go home but not sick enough to need hospitalization.

Staffing shortages at post-acute facilities around the country led to a 24% increase over three years in hospital length of stay among patients who need skilled nursing care, according to a 2022 analysis. With no place to go, these patients occupy expensive hospital beds they don’t need, while others wait in emergency rooms for those spots. In Massachusetts, for example, at least 1,995 patients were awaiting hospital discharge in December, according to a survey of hospitals by the Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association.

Offering intensive services and remote monitoring technology in the home can work as an alternative — especially in rural areas, where nursing homes are closing at a faster rate than in cities and patients’ relatives often must travel far to visit. For patients of the Marshfield Clinic Health System who live in rural parts of Wisconsin, the clinic’s six-year-old SNF-at-home program is often the only option, said Swetha Gudibanda, medical director of the hospital-at-home program.

“This is going to be the future of medicine,” Gudibanda said.

But the concept is new, an outgrowth of hospital-at-home services expanded by a covid-19 pandemic-inspired Medicare waiver. SNF-at-home care remains uncommon, lost in a fiscal and regulatory netherworld. No federal standards spell out how to run these programs, which patients should qualify, or what services to offer. No reimbursement mechanism exists, so fee-for-service Medicare and most insurance companies don’t cover such care at home.

The programs have emerged only at a few hospital systems with their own insurance companies (like the Marshfield Clinic) or those that arrange for “bundled payments,” in which providers receive a set fee to manage an episode of care, as can occur with Medicare Advantage plans.

In Durocher’s case, the care was available — at no cost to him or other patients — only through the clinical trial, funded by a grant from the state Medicaid program. State health officials supported two simultaneous studies at UMass and Mass General Brigham hoping to reduce costs, improve quality of care, and, crucially, make it easier to transition patients out of the hospital.

The American Health Care Association, the trade group representing more than 15,000 long-term and post-acute care providers, calls “SNF at home” a misnomer because, by law, such services must be provided in an institution and meet detailed requirements. And the association points out that skilled nursing facilities provide services and socialization that can never be replicated at home, such as daily activity programs, religious services, and access to social workers.

But patients at home tend to get up and move around more than those in a facility, speeding their recovery, said Wendy Mitchell, medical director of the UMass Chan clinical trial. Also, therapy is tailored to their home environment, teaching patients to navigate the exact stairs and bathrooms they’ll eventually use on their own.

A quarter of people who go into nursing homes suffer an “adverse event,” such as infection or bed sore, said David Levine, clinical director for research for Mass General Brigham’s Healthcare at Home program and leader of its study. “We cause a lot of harm in facility-based care,” he said.

By contrast, in 2024, not one patient in the Rehabilitation Care at Home program of Nashville-based Contessa Health developed a bed sore and only 0.3% came down with an infection while at home, according to internal company data. Contessa delivers care in the home through partnerships with five health systems, including Mount Sinai Health System in New York City, the Allegheny Health Network in Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin’s Marshfield Clinic.

Contessa’s program, which has been providing in-home post-hospital rehabilitation since 2019, depends on help from unpaid family caregivers. “Almost universally, our patients have somebody living with them,” said Robert Moskowitz, Contessa’s acting president and chief medical officer.

The two Massachusetts-based studies, however, do enroll patients who live alone. In the UMass trial, an overnight home health aide can stay for a day or two if needed. And while alone, patients “have a single-button access to a live person from our command center,” said Apurv Soni, an assistant professor of medicine at UMass Chan and the leader of its study.

But SNF at home is not without hazards, and choosing the right patients to enroll is critical. The UMass research team learned an important lesson when a patient with mild dementia became alarmed by unfamiliar caregivers coming to her home. She was readmitted to the hospital, according to Mitchell.

The Mass General Brigham study relies heavily on technology intended to reduce the need for highly skilled staff. A nurse and physician each conducts an in-home visit, but the patient is otherwise monitored remotely. Medical assistants visit the home to gather data with a portable ultrasound, portable X-ray, and a device that can analyze blood tests on-site. A machine the size of a toaster oven dispenses medication, with a robotic arm that drops the pills into a dispensing unit.

The UMass trial, the one Durocher enrolled in, instead chose a “light touch” with technology, using only a few devices, Soni said.

The day Durocher went home, he said, a nurse met him there and showed him how to use a wireless blood pressure cuff, wireless pulse oximeter, and digital tablet that would transmit his vital signs twice a day. Over the next few days, he said, nurses came by to take blood samples and check on him. Physical and occupational therapists provided several hours of treatment every day, and a home health aide came a few hours a day. To his delight, the program even sent three meals a day.

Durocher learned to use the walker and how to get up the stairs to his bedroom with one crutch and support from his wife. After just one week, he transitioned to less-frequent, in-home physical therapy, covered by his insurance.

“The recovery is amazing because you’re in your own setting,” Durocher said. “To be relegated to a chair and a walker, and at first somebody helping you get up, or into bed, showering you — it’s very humbling. But it’s comfortable. It’s home, right?”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Your Neighbor Has Backyard Chickens. Should You Be Worried?

If your neighbor is a backyard chicken hobbyist, should you be worried about bird flu? KFF Health News national public health correspondent Amy Maxmen answers that question and shares her reporting, on WAMU’s “Health Hub” segment March 5. The latest outbreak of bird flu has […]

Rural HealthIf your neighbor is a backyard chicken hobbyist, should you be worried about bird flu? KFF Health News national public health correspondent Amy Maxmen answers that question and shares her reporting, on WAMU’s “Health Hub” segment March 5.

The latest outbreak of bird flu has upended egg, poultry, and dairy operations, sickened dozens of farmworkers, and killed at least one person in the U.S. Traditional methods to curb H5N1 have so far failed. While the virus isn’t known to be spreading between people, each new infection is a chance for it to evolve. That could set the stage for another pandemic.

Scientists worry the United States isn’t doing enough to track and curb the virus. On WAMU’s “Health Hub,” KFF Health News public health correspondent Amy Maxmen explains the threat bird flu poses to public health and actions the government is taking to control the outbreak.

KFF Health News producer Taylor Cook contributed reporting to this segment.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Millions in US Live in Places Where Doctors Don’t Practice and Telehealth Doesn’t Reach

BOLIGEE, Ala. — Green lights flickered on the wireless router in Barbara Williams’ kitchen. Just one bar lit up — a weak signal connecting her to the world beyond her home in the Alabama Black Belt. If you regularly experience connection issues, click here to read […]

Rural HealthBOLIGEE, Ala. — Green lights flickered on the wireless router in Barbara Williams’ kitchen. Just one bar lit up — a weak signal connecting her to the world beyond her home in the Alabama Black Belt.

If you regularly experience connection issues, click here to read a version of this story designed to open faster in low-signal areas.

Next to the router sat medications, vitamin D pills, and Williams’ blood glucose monitor kit.

“I haven’t used that thing in a month or so,” said Williams, 72, waving toward the kit. Diagnosed with diabetes more than six years ago, she has developed nerve pain from neuropathy in both legs.

Williams is one of nearly 3 million Americans who live in mostly rural counties that lack both health care and reliable high-speed internet, according to an analysis by KFF Health News, which showed that these people tend to live sicker and die younger than others in America.

Compared with those in other regions, patients across the rural South, Appalachia, and remote West are most often unable to make a video call to their doctor or log into their patient portals. Both are essential ways to participate in the U.S. medical system. And Williams is among those who can do neither.

This year, more than $42 billion allocated in the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act is expected to begin flowing to states as part of a national “Internet for All” initiative launched by the Biden administration. But the program faces uncertainty after Commerce Department Secretary Howard Lutnick last week announced a “rigorous review” asserting that the previous administration’s approach was full of “woke mandates.”

High rates of chronic illness and historical inequities are hallmarks of many of the more than 200 U.S. counties with poor services that KFF Health News identified. Dozens of doctors, academics, and advocates interviewed for this article unanimously agreed that limited internet service hinders medical care and access.

Without fast, reliable broadband, “all we’re going to do is widen health care disparities within telemedicine,” said Rashmi Mullur, an endocrinologist and chief of telehealth at VA Greater Los Angeles. Patients with diabetes who also use telemedicine are more likely to get care and control their blood sugar, Mullur found.

Diabetes requires constant management. Left untreated, uncontrolled blood sugar can cause blindness, kidney failure, nerve damage, and eventually death.

Williams, who sees a nurse practitioner at the county hospital in the next town, said she is not interested in using remote patient monitoring or video calls.

“I know how my sugar affects me,” Williams said. “I get a headache if it’s too high.” She gets weaker when it’s down, she said, and always carries snacks like crackers or peppermints.

Williams said she could even drink a soda pop — orange, grape — when her sugar is low but would not drink one when she felt it was high because she would get “kind of goozie-woozy.”

‘This Is America’

Connectivity dead zones persist in American life despite at least $115 billion lawmakers have thrown toward fixing the inequities. Federal broadband efforts are fragmented and overlapping, with more than 133 funding programs administered by 15 agencies, according to a 2023 federal report.

“This is America. It’s not supposed to be this way,” said Karthik Ganesh, chief executive of Tampa, Florida-based OnMed, a telehealth company that in September installed a walk-in booth at the Boligee Community Center about 10 minutes from Williams’ home. Residents can call up free life-size video consultations with an OnMed health care provider and use equipment to check their weight and blood pressure.

OnMed, which partnered with local universities and the Alabama Cooperative Extension System, relies on SpaceX’s Starlink to provide a high-speed connection in lieu of other options.

A short drive from the community center, beyond Boligee’s Main Street with its deserted buildings and an empty railroad depot and down a long gravel drive, is the 22-acre property where Williams lives.

Last fall, Williams washed a dish in her kitchen, with its unforgiving linoleum-topped concrete floors. A few months earlier, she said, a man at the community center signed her up for “diabetic shoes” to help with her sore feet. They never arrived.

As Williams spoke, steam rose from a pot of boiling potatoes on the stove. Another pan sizzled with hamburger steak. And on a back burner simmered a mix of Velveeta cheese, diced tomatoes, and peppers.

She spent years on her feet as head cook at a diner in Cleveland, Ohio. The oldest of nine, Williams returned to her family home in Greene County more than 20 years ago to care for her mother and a sister, who both died from cancer in the back bedroom where she now sleeps.

Williams looked out a window and recalled when the landscape was covered in cotton that she once helped pick. Now three houses stand in a carefully tended clearing surrounded by tall trees. One belongs to a brother and the other to a sister who drives with her daily to the community center for exercise, prayers, and friendship with other seniors.

All the surviving siblings, Williams said, have diabetes. “I don’t know how we became diabetic,” she said. Neither of their parents had been diagnosed with the illness.

In Greene County, an estimated quarter of adults have diabetes — twice the national average. The county, which has about 7,600 residents, also has among the nation’s highest rates for several chronic diseases such as high blood pressure, stroke, and obesity, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data shows.

The county’s population is predominately Black. The federal CDC reports that Black Americans are more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes and are 40% more likely than their white counterparts to die from the condition. And in the South, rural Black residents are more likely to lack home internet access, according to the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, a Washington-based think tank.

To identify counties most lacking in reliable broadband and health care providers, KFF Health News used data from the Federal Communications Commission and George Washington University’s Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity. Reporters also analyzed U.S. Census Bureau, CDC, and other data to understand the health status and demographics of those counties.

The analysis confirms that internet and care gaps are “hitting areas of extreme poverty and high social vulnerability,” said Clese Erikson, deputy director of the health workforce research center at the Mullan Institute.

Digital Haves vs. Have-Nots

Just over half of homes in Greene County have access to reliable high-speed internet — among the lowest rates in the nation. Greene County also has some of the country’s poorest residents, with a median household income of about $31,500. Average life expectancy is less than 72 years, below the national average.

By contrast, the KFF Health News analysis found that counties with the highest rates of internet access and health care providers correlated with higher life expectancy, less chronic disease, and key lifestyle factors such as higher incomes and education levels.

One of those is Howard County, Maryland, between Baltimore and Washington, D.C., where nearly all homes can connect to fast, reliable internet. The median household income is about $147,000 and average life expectancy is more than 82 years — a decade longer than in Greene County. A much smaller share of residents live with chronic conditions such as diabetes.

One is 78-year-old Sam Wilderson, a retired electrical engineer who has managed his Type 2 diabetes for more than a decade. He has fiber-optic internet at his home, which is a few miles from a cafe he dines at every week after Bible study. On a recent day, the cafe had a guest Wi-Fi download speed of 104 megabits per second and a 148 Mbps upload speed. The speeds are fast enough for remote workers to reliably take video calls.

Americans are demanding more speed than ever before. Most households have multiple devices — televisions, computers, gaming systems, doorbells — in addition to phones that can take up bandwidth. The more devices connected, the higher minimum speeds are needed to keep everything running smoothly.

To meet increasing needs, federal regulators updated the definition of broadband last year, establishing standard speeds of 100/20 Mbps. Those speeds are typically enough for several users to stream, browse, download, and play games at the same time.

Christopher Ali, professor of telecommunications at Penn State, recommends minimum standard speeds of 100/100 Mbps. While download speeds enable consumption, such as streaming or shopping, fast upload speeds are necessary to participate in video calls, say, for work or telehealth.

At the cafe in Howard County, on a chilly morning last fall, Wilderson ordered a glass of white wine and his usual: three-seeded bread with spinach, goat cheese, smoked salmon, and over-easy eggs. After eating, Wilderson held up his wrist: “This watch allows me to track my diabetes without pricking my finger.”

Wilderson said he works with his doctors, feels young, and expects to live well into his 90s, just as his father and grandfather did.

Telehealth is crucial for people in areas with few or no medical providers, said Ry Marcattilio, an associate director of research at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. The national research and advocacy group works with communities on broadband access and reviewed KFF Health News’ findings.

High-speed internet makes it easier to use video visits for medical checkups, which most patients with diabetes need every three months.

Being connected “can make a huge difference in diabetes outcomes,” said Nestoras Mathioudakis, an endocrinologist and the co-medical director of Johns Hopkins Medicine Diabetes & Education Program, who treats patients in Howard County.

Paying More for Less

At Williams’ home in Alabama, pictures of her siblings and their kids cover the walls of the hallway and living room. A large, wood-framed image of Jesus at the Last Supper with his disciples hangs over her kitchen table.

Williams sat down as her pots simmered and sizzled. She wasn’t feeling quite right. “I had a glass of orange juice and a bag of potato chips, and I knew that wasn’t enough for breakfast, but I was cooking,” Williams said.

Every night Williams takes a pill to control her diabetes. In the morning, if she feels as if her sugar is dropping, she knows she needs to eat. So, that morning, she left the room to grab a peppermint, walking by the flickering wireless router.

The router’s download and upload speeds were 0.03/0.05 Mbps, nearly unusable by modern standards. Williams’ connection on her house phone can sound scratchy, and when she connects her cellphone to the router, it does not always work. Most days it’s just good enough for her to read a daily devotional website and check Facebook, though the stories don’t always load.

Rural residents like Williams paid nearly $13 more a month on average in late 2020 for slow internet connections than those in urban areas, according to Brian Whitacre, an agricultural economics professor at Oklahoma State University.

“You’re more likely to have competition in an urban area,” Whitacre said.

In rural Alabama, cellphone and internet options are limited. Williams pays $51.28 a month to her wireless provider, Ring Planet, which did not respond to calls and emails.

In Howard County, Maryland, national fiber-optic broadband provider Verizon Communications faces competition from Comcast, a hybrid fiber-optic and cable provider. Verizon advertises a home internet plan promising speeds of 300/300 Mbps starting at $35 a month for its existing mobile customers. The company also offers a discounted price as low as $20 a month for customers who participate in certain federal assistance programs.

“Internet service providers look at the economics of going into some of these communities and there just isn’t enough purchasing power in their minds to warrant the investment,” said Ross DeVol, chief executive of Heartland Forward, a nonpartisan think tank based in Bentonville, Arkansas, that specializes in state and local economic development.

Conexon, a fiber-optic cable construction company, estimates it costs $25,000 per mile to build above-ground fiber lines on poles and $60,000 to $70,000 per mile to build underground.

Former President Joe Biden’s 2021 infrastructure law earmarked $65 billion with a goal of connecting all Americans to high-speed internet. Money was designated to establish digital equity programs and to help low-income customers pay their internet bills. The law also set aside tens of billions through the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program, known as BEAD, to connect homes and businesses.

That effort prioritizes fiber-optic connections, but federal regulators recently outlined guidance for alternative technologies, including low Earth orbit satellites like SpaceX’s Starlink service.

Funding the use of satellites in federal broadband programs has been controversial inside federal agencies. It has also been a sore point for Elon Musk, who is chief executive of SpaceX, which runs Starlink, and is a lead adviser to President Donald Trump.

After preliminary approval, a federal commission ruled that Starlink’s satellite system was “not reasonably capable” of offering reliable high speeds. Musk tweeted last year that the commission had “illegally revoked” money awarded under the agency’s Trump-era Rural Digital Opportunity Fund.

In February, Trump nominated Arielle Roth to lead the federal agency overseeing the infrastructure act’s BEAD program. Roth is telecommunications policy director for the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. Last year, she criticized the program’s emphasis on fiber and said it was beleaguered by a “woke social agenda” with too many regulations.

Commerce Secretary Lutnick last week said he will get rid of “burdensome regulations” and revamp the program to “take a tech-neutral approach.” Republicans echoed his positions during a U.S. House subcommittee hearing the same day.

When asked about potentially weakening the program’s required low-cost internet option, former National Telecommunications and Information Administration official Sarah Morris said such a change would build internet connections that people can’t afford. Essentially, she said, they would be “building bridges to nowhere, building networks to no one.”

‘That Hurt’

Over a lunch of tortilla chips with the savory sauce that had been simmering on the stove, Williams said she hadn’t been getting regular checkups before her diabetes diagnosis.

“To tell you the truth, if I can get up and move and nothing is bothering me, I don’t go to the doctor,” Williams said. “I’m just being honest.”

Years ago, Williams recalled, “my head was hurting me so bad I had to just lay down. I couldn’t stand up, walk, or nothing. I’d get so dizzy.”

Williams thought it was her blood pressure, but the doctor checked for diabetes. “How did they know? I don’t know,” Williams said.

As lunch ended, she pulled out her glucose monitor. Williams connected the needle and wiped her finger with an alcohol pad. Then she pricked her finger.

“Oh,” Williams said, sucking air through her teeth. “That hurt.”

She placed the sample in the machine, and it quickly displayed a reading of 145 — a number, Williams said, that meant she needed to stop eating.

Click to open the Methodology

Methodology

Here’s how KFF Health News did its analysis for the “Dead Zone” series, which pinpointed counties that lag behind the rest of the United States in access to broadband service and health care providers.

To identify “dead zones,” KFF Health News consulted two main data sources.

- The Federal Communications Commission National Broadband Map was used to identify broadband deserts as of June 2024. We used the FCC’s minimum speed standard of 100 Mbps download and 20 Mbps upload, and followed its definition of reliable broadband: service accessible via wired (fiber optics, cable, DSL) or licensed fixed wireless technology. It’s the standard for grants awarded through the federal Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program, known as BEAD. The FCC data shows whether such service is available, and not necessarily whether households subscribe to it.

- Data from George Washington University’s Fitzhugh Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity was used to determine counties with health provider shortages. GWU’s data on primary care providers (family and internal medicine doctors, pediatricians, obstetricians and gynecologists, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) reflects providers who serve at least one person enrolled in Medicaid. We used the most recent years available: 2020 for 44 states, and 2019 data for Texas. Five states — Delaware, Florida, Maine, Minnesota, and New Hampshire — were excluded from analysis because they lacked reliable data for either year.

GWU’s data for behavioral health providers reflects psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors, therapists, and addiction medicine specialists, regardless of whether their patients receive Medicaid. We used data from 2021, the most recent year available.

We classified counties as “dead zones” if they met these criteria:

- Fewer than 70% of homes had access to fast, reliable broadband.

- They ranked in the bottom third of Medicaid primary care providers, defined as the number of Medicaid enrollees per provider.

- They ranked in the bottom third of behavioral health providers, defined as the number of residents per provider.

A total of 210 counties met those criteria. At the other extreme, we defined 203 counties as “most served” if they had the most residences with broadband access (at least 96.7%) and ranked in the top third of Medicaid primary care and behavioral health provider ratios.

We also compared the health outcomes and demographics of dead zone counties relative to others using several data sources:

- U.S. Census Bureau, for data on household income, education levels, and other demographics.

- County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, part of the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, for data on life expectancy and the percentage of residents living in rural areas.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for data on diabetes, high blood pressure, and other chronic health conditions.

This project was produced in partnership with InvestigateTV. InvestigateTV is Gray Television’s national investigative team and provides innovative, original journalism from a dedicated investigative team and partners, as well as weekday and weekend shows. Gray is the nation’s second-largest television broadcaster, with television stations serving 113 markets.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

States Facing Doctor Shortages Ease Licensing Rules for Foreign-Trained Physicians

A growing number of states have made it easier for doctors who trained in other countries to get medical licenses, a shift supporters say could ease physician shortages in rural areas. The changes involve residency programs — the supervised, hands-on training experience that doctors must […]

Rural HealthA growing number of states have made it easier for doctors who trained in other countries to get medical licenses, a shift supporters say could ease physician shortages in rural areas.

The changes involve residency programs — the supervised, hands-on training experience that doctors must complete after graduating medical school. Until recently, every state required physicians who completed a residency or similar training abroad to repeat the process in the U.S. before obtaining a full medical license.

Since 2023, at least nine states have dropped this requirement for some doctors with international training, according to the Federation of State Medical Boards. More than a dozen other states are considering similar legislation.

About 26% of doctors who practice in the U.S. were born elsewhere, according to the Migration Policy Institute. They need federal visas to live in the U.S., plus state licenses to practice medicine.

Proponents of the new laws say qualified doctors shouldn’t have to spend years completing a second residency training. Opponents worry about patient safety and doubt the licensing change will ease the doctor shortage.

Lawmakers in Republican- and Democratic-leaning states have approved the idea at a time when many other immigration-related programs are under attack. They include Florida, Iowa, Idaho, Illinois, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Tennessee, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

President Donald Trump has defended a federal visa program that many foreign doctors rely on, but they could still be hampered by his broad efforts to tighten immigration rules.

Supporters of the new licensing laws include Zalmai Afzali, an internal medicine doctor who finished medical school and a residency program in Afghanistan before fleeing the Taliban and coming to the U.S. in 2001.

He said most physicians trained elsewhere would be happy to work in rural or other underserved areas.

“I would go anywhere as long as they let me work,” said Afzali, who now treats patients who live in rural areas and small cities in northeastern Virginia. “I missed being a physician. I missed what I did.”

It took Afzali 12 years to obtain copies of his diploma and transcript, study for exams, and finish a three-year U.S.-based residency program before he could be fully licensed to practice as a doctor in his new country.

But a commission of national health organizations questions whether loosening residency requirements for foreign-trained doctors would ease the shortage. Doctors in these programs could still face licensing and employment barriers, it wrote in a report that makes recommendations without taking a stance on such legislation.

Erin Fraher, a health policy professor at the University of North Carolina who advises the commission and studies the issue, said lawmakers who support the changes predict they will boost the rural health workforce. But it’s unclear whether that will happen, she said, because the programs are just getting started.

“I think the potential is there, but we need to see how this pans out,” Fraher said.

Afzali struggled to support his family while trying to get his medical license. His jobs included working at a department store for $7.25 an hour and administering chemotherapy for $20 an hour. Afzali said nurse practitioners at the latter job had less training than him but earned nearly four times as much.

“I do not know how I did it,” he said. “I mean, you get really depressed.”

Many of the state bills to ease residency requirements have been based on model legislation from the Cicero Institute, a conservative think tank that sent representatives to testify to legislatures after proposing such programs in 2020.

The new pathways are open only to internationally trained physicians who meet certain conditions. Common requirements include working as a physician for several years after graduating from a medical school and residency program with similar rigor to those found in the U.S. They also must pass the standard three-part exam that all physicians take to become licensed in the U.S.

Those who qualify are granted a restricted license to practice, and most states require them to do so under supervision of another physician. They can receive full licensure after several years.

About 10 of the laws or bills also require the doctors to work for several years in a rural or underserved area.

But states without this requirement, such as Tennessee, may not see an impact in rural areas, researchers from Harvard Medical School and Rand Corp. argued in the New England Journal of Medicine. In addition to including that condition, states could offer incentives to rural hospitals that agree to hire doctors from the new training pathways, they wrote.

Lawmakers, physicians, and health organizations that oppose the changes say there are better ways to safely increase the number of rural doctors.

Barbara Parker is a registered nurse and former Republican lawmaker in Arizona, where the legislature is considering a bill for at least the fourth year in a row.

“It’s a really poor answer to the doctor shortage,” said Parker, who voted against the legislation last year.

Parker said making it easier for foreign-trained physicians to practice in the U.S. would unethically poach doctors from countries with greater health care needs. And she said she doubts that all international residencies are on par with those in the U.S. and worries that granting licenses to physicians who trained in them could lead to poor care for patients.

She is also concerned that hospitals are trying to save money by recruiting internationally trained doctors over those trained in the U.S. The former often will accept lower pay, Parker said.

“This is driven by corporate greed,” she said.

Parker said better ways to increase the number of rural doctors include raising pay, expanding loan repayment programs for those who practice in rural areas, and creating accelerated training for nurse practitioners and physician assistants who want to become doctors.

The advisory commission — recently formed by the Federation of State Medical Boards, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, and Intealth, a nonprofit that evaluates international medical schools and their graduates — published its recommendations to help lawmakers and medical boards make sure these new pathways are safe and effective.

The commission and Fraher said state medical boards should collect data on the new rules, such as how many doctors participate, what their specialties are, and where they work once they gain their full licenses. The results could be compared with other methods of easing the rural doctor shortage, such as adding residency programs at rural hospitals.

“What is the benefit of this particular pathway relative to other levers that they have?” Fraher said.

The commission noted that while state medical boards can rely on an outside organization that evaluates the strength of foreign medical schools, there isn’t a similar rating for residency programs. Such an effort is expected to launch in mid-2025, the commission said.

The group also said states should require supervising physicians to evaluate participants before they’re granted a full license.

Afzali, the physician from Afghanistan, said some internationally trained primary care doctors have more training than their U.S. counterparts, because they had to practice procedures that are done only by specialists in the U.S.

But he agreed with the commission’s recommendation that states require doctors who did residencies abroad to have supervision while they hold a provisional license. That would help ensure patient safety while also helping the physicians adjust to cultural differences and learn the technical side of the U.S. health system, such as billing and electronic health records, the commission wrote.

Fraher noted that doctors in programs with supervision requirements need to find an experienced colleague with the time and interest in providing this oversight at a health facility willing to hire them.

The commission pointed out other potential hurdles, such as malpractice insurers possibly declining to cover physicians who obtain state licenses without completing a U.S. residency. The commission and the American Board of Medical Specialties also pointed to the issue of specialty certification, which is managed by national organizations that have their own residency requirements.

Physicians who aren’t eligible to take board exams could lose out on employment opportunities, and patients might have concerns about their qualifications, the board wrote. But it said a majority of its member boards would consider certifying these doctors if states added requirements it recommended.

Lawmakers’ plans to use these new licensing pathways to increase the number of rural doctors will require the foreign-trained doctors to navigate all these obstacles and unknowns, Fraher said.

“There’s a lot of things that need to happen to make this a reality,” she said.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

With RFK Jr. in Charge, Supplement Makers See Chance To Cash In

Last fall, before being named the senior U.S. health official, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said the Trump administration would liberate Americans from the FDA’s “aggressive suppression” of vitamins, dietary supplements, and other substances — ending the federal agency’s “war on public health,” as he put […]

PharmaceuticalsLast fall, before being named the senior U.S. health official, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said the Trump administration would liberate Americans from the FDA’s “aggressive suppression” of vitamins, dietary supplements, and other substances — ending the federal agency’s “war on public health,” as he put it.

In fact, the FDA can’t even require that supplements be effective before they are sold. When Congress, at the agency’s urging, last considered legislation to require makers of vitamins, herbal remedies, and other pills and potions to show proof of their safety and worth before marketing the products, it got more negative mail, phone calls, and telegrams than at any time since the Vietnam War, by some accounts. The backlash resulted in a 1994 law that enabled the dietary supplement industry to put its products on the market without testing and to tout unproven benefits, as long as the touting doesn’t include claims to treat or cure a disease. Annual industry revenues have grown from $4 billion to $70 billion since.

With Kennedy now in the driver’s seat, the industry will likely expect more: It aims to make bolder health claims for its products and even get the government, private insurers, and flexible spending accounts to pay for supplements, essentially putting them on an equal footing with FDA-approved pharmaceuticals.

On Feb. 13, the day Kennedy was sworn in as secretary of Health and Human Services, President Donald Trump issued a “Make America Healthy Again” agenda targeting alleged corruption in health regulatory agencies and instructing them to “ensure the availability of expanded treatment options and the flexibility for health insurance coverage to provide benefits that support beneficial lifestyle changes and disease prevention.”

Kennedy has said exercise, dietary supplements, and nutrition, rather than pharmaceutical products, are key to good health. Supplement makers want consumers to be able to use programs like health savings accounts, Medicare, and even benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, to pay for such items as vitamins, fish oil, protein powders, and probiotics.

“Essentially they’re seeking a government subsidy,” said Pieter Cohen, a Harvard University physician who studies supplements.

As the Senate Finance Committee questioned Kennedy during his Jan. 29 confirmation hearing, supporters in the Alliance for Natural Health lunched on quinoa salad in the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center and crowed that the moment had finally arrived for their health freedom movement, which has combined libertarian capitalism and mistrust of the medical establishment to champion unregulated compounds since the 19th century.

“The greatest opportunity of our lifetimes is before us,” said Jonathan Emord, the group’s general counsel, who has brought many successful lawsuits against the FDA’s restrictions on unproven health claims. “RFK has dedicated his whole life to opposing the undue influence” of the pharmaceutical industry and “assuring that our interests triumph,” Emord said.

In speeches and in a pamphlet called “The MAHA Mandate,” Emord and alliance founder Robert Verkerk said Kennedy would free companies to make greater claims for their products’ alleged benefits. Emord said his group was preparing to sue the FDA to prevent it from restricting non-pharmaceutical production of substances like biopeptides — complex molecules related to drugs like Ozempic.

HHS spokesperson Andrew Nixon did not respond to a request for comment on the agency’s plans vis-à-vis dietary supplements.

While the basic law governing the FDA establishes that a substance alleged to have treatment or curative effects is by definition a “drug,” and therefore comes under the agency’s requirements for high standards of scientific evidence, the new administration could reallocate money away from enforcement, said Mitch Zeller, former head of the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products.

As a Senate aide early in his career, Zeller investigated a tainted L-tryptophan supplement that killed at least 30 people and sickened thousands in the U.S. in 1989. The scandal led the FDA to seek heavier regulation of supplements, but a powerful backlash resulted in the relatively weak supplements law of 1994.

Even that law’s enforcement could be undercut with a stroke of the pen that would keep FDA inspectors out of the field, Zeller said.

Sweeping changes couldn’t come too soon for Nathan Jones, founder and CEO of Xlear, a company that makes products containing xylitol, an artificial sweetener. The Federal Trade Commission sued Xlear in 2021 for making what it called false claims that its nasal spray could prevent and treat covid.

Jones points to a handful of studies evaluating whether xylitol prevents cavities and infections, saying the FDA would require overly expensive studies to get xylitol approved as a drug. Meanwhile, he said, dentists have been bought out by “Big Toothpaste.”

One can hardly find any products “without fluoride for oral health,” he said. “Crest and Colgate don’t want it to happen,” he said.

Kennedy’s desire to rid water supplies of fluoride because of its alleged impact on children’s IQ is welcome news, he said, and not only because it could highlight the value of his products. Jones stresses, as do many health freedom advocates, that clean air and water and unadulterated food do more to prevent and cure disease than vaccines and drugs. For example, he and other advocates claim, wrongly, that the United States eliminated the crippling disease polio through better sanitation, not vaccination.

The Alliance for Natural Health hopes that in lieu of strict FDA standards, Kennedy will enable companies to make expanded marketing claims based on evidence from non-FDA sources, Verkerk said, such as the National Institutes of Health’s nutritional information site, which describes the pros and cons of different supplements.

Kennedy has also called for relaxing the strictures on psychedelic drugs, which interest some veterans as potential remedies for such conditions as post-traumatic stress disorder. VETS, a San Diego-based organization, has paid for 1,000 veterans to get treatment with the powerful hallucinogen ibogaine at clinics in Mexico and other countries, said the group’s co-founder Amber Capone.

She got involved after her husband, a retired Navy SEAL, pulled out of a suicidal spiral after spending a week at an ibogaine clinic near Tijuana, Mexico, in 2017. She wants NIH, the Defense Department, and the Department of Veterans Affairs to fund research on the illegal substance — which can cause cardiac complications and is listed as a Schedule I drug, on par with heroin and LSD — so it can be made legally available when appropriate.

Coincidentally, the push for less onerous standards on supplements and psychedelics would come while Kennedy is demanding “gold-standard science” to review preservatives and other food additives that he has said could play a role in the country’s high rate of chronic diseases.

“Put aside the fact that there’s precious little evidence to support” that idea, said Stuart Pape, a former FDA food center attorney. “There’s been no indication they want the same rigor for supplements and nutraceuticals.”

Although most of these products don’t have major safety concerns, “we have no idea which products work, so in the best case people are throwing away a ton of money,” Zeller said. “The worst-case scenario is they are relying on unproven products to treat underlying conditions, and time is going by when they could have been using more effective FDA-authorized products for diseases.”

Supplement makers aren’t entirely unified. Groups such as the Consumer Healthcare Products Association and the Council for Responsible Nutrition have advocated for the FDA to crack down on products that are unsafe or falsely represented. The Alliance for Natural Health and the Natural Products Association, meanwhile, largely want the government to get out of the way.

“The time has come to embrace a radical shift — from reactive disease management to proactive health cultivation, from top-down public health diktats to personalized, individual-centric care,” Emord and Verkerk state in their “MAHA Mandate.”

We’d like to speak with current and former personnel from the Department of Health and Human Services or its component agencies who believe the public should understand the impact of what’s happening within the federal health bureaucracy. Please message KFF Health News on Signal at (415) 519-8778 or get in touch here.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Journalists Discuss Health Care for Incarcerated Children and the Possibility of a Bird Flu Pandemic

KFF Health News editor-at-large for public health Céline Gounder discussed the possibility of a bird flu pandemic on WAMU’s “1A” on Feb. 20. Gounder also discussed the potential of an off-label drug being studied to help some autistic kids improve their ability to speak on […]

PharmaceuticalsKFF Health News editor-at-large for public health Céline Gounder discussed the possibility of a bird flu pandemic on WAMU’s “1A” on Feb. 20. Gounder also discussed the potential of an off-label drug being studied to help some autistic kids improve their ability to speak on CBS News’ “CBS Evening News” on Feb. 17.

KFF Health News senior correspondent Renuka Rayasam discussed the expansion of health care access to incarcerated youths on WUGA’s “The Georgia Health Report” on Feb. 14.

- Click here to hear Rayasam on “The Georgia Health Report”

- Read Rayasam’s “Some Incarcerated Youths Will Get Health Care After Release Under New Law”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Pain Clinics Made Millions From ‘Unnecessary’ Injections Into ‘Human Pin Cushions’

McMINNVILLE, Tenn. — Each month, Michelle Shaw went to a pain clinic to get the shots that made her back feel worse — so she could get the pills that made her back feel better. Shaw, 56, who has been dependent on opioid painkillers since […]

PharmaceuticalsMcMINNVILLE, Tenn. — Each month, Michelle Shaw went to a pain clinic to get the shots that made her back feel worse — so she could get the pills that made her back feel better.

Shaw, 56, who has been dependent on opioid painkillers since she injured her back in a fall a decade ago, said in both an interview with KFF Health News and in sworn courtroom testimony that the Tennessee clinic would write the prescriptions only if she first agreed to receive three or four “very painful” injections of another medicine along her spine.

The clinic claimed the injections were steroids that would relieve her pain, Shaw said, but with each shot her agony would grow. Shaw said she eventually tried to decline the shots, then the clinic issued an ultimatum: Take the injections or get her painkillers somewhere else.

“I had nowhere else to go at the time,” Shaw testified, according to a federal court transcript. “I was stuck.”

Shaw was among thousands of patients of Pain MD, a multistate pain management company that was once among the nation’s most prolific users of what it referred to as “tendon origin injections,” which normally inject a single dose of steroids to relieve stiff or painful joints. As many doctors were scaling back their use of prescription painkillers due to the opioid crisis, Pain MD paired opioids with monthly injections into patients’ backs, claiming the shots could ease pain and potentially lessen reliance on painkillers, according to federal court documents.

Now, years later, Pain MD’s injections have been proved in court to be part of a decade-long fraud scheme that made millions by capitalizing on patients’ dependence on opioids. The Department of Justice has successfully argued at trial that Pain MD’s “unnecessary and expensive injections” were largely ineffective because they targeted the wrong body part, contained short-lived numbing medications but no steroids, and appeared to be based on test shots given to cadavers — people who felt neither pain nor relief because they were dead.

Four Pain MD employees have pleaded guilty or been convicted of health care fraud, including company president Michael Kestner, who was found guilty of 13 felonies at an October trial in Nashville, Tennessee. According to a transcript from Kestner’s trial that became public in December, witnesses testified that the company documented giving patients about 700,000 total injections over about eight years and said some patients got as many as 24 shots at once.

“The defendant, Michael Kestner, found out about an injection that could be billed a lot and paid well,” said federal prosecutor James V. Hayes as the trial began, according to the transcript. “And they turned some patients into human pin cushions.”

The Department of Justice declined to comment for this article. Kestner’s attorneys either declined to comment or did not respond to requests for an interview. At trial, Kestner’s attorneys argued that he was a well-intentioned businessman who wanted to run pain clinics that offered more than just pills. He is scheduled to be sentenced on April 21 in a federal court in Nashville.

According to the transcript of Kestner’s trial, Shaw and three other former patients testified that Pain MD’s injections did not ease their pain and sometimes made it worse. The patients said they tolerated the shots only so Pain MD wouldn’t cut off their prescriptions, without which they might have spiraled into withdrawal.

“They told me that if I didn’t take the shots — because I said they didn’t help — I would not get my medication,” testified Patricia McNeil, a former patient in Tennessee, according to the trial transcript. “I took the shots to get my medication.”

In her interview with KFF Health News, Shaw said that often she would arrive at the Pain MD clinic walking with a cane but would leave in a wheelchair because the injections left her in too much pain to walk.

“That was the pain clinic that was supposed to be helping me,” Shaw said in her interview. “I would come home crying. It just felt like they were using me.”

‘Not Actually Injections Into Tendons at All’

Pain MD, which sometimes operated under the name Mid-South Pain Management, ran as many as 20 clinics in Tennessee, Virginia, and North Carolina throughout much of the 2010s. Some clinics averaged more than 12 injections per patient each month, and at least two patients each received more than 500 shots in total, according to federal court documents.

All those injections added up. According to Medicare data filed in federal court, Pain MD and Mid-South Pain Management billed Medicare for more than 290,000 “tendon origin injections” from January 2010 to May 2018, which is about seven times that of any other Medicare biller in the U.S. over the same period.

Tens of thousands of additional injections were billed to Medicaid and Tricare during those same years, according to federal court documents. Pain MD billed these government programs for about $111 per injection and collected more than $5 million from the government for the shots, according to the court documents.

More injections were billed to private insurance too. Christy Wallace, an audit manager for BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee, testified that Pain MD billed the insurance company about $40 million for more than 380,000 injections from January 2010 to March 2013. BlueCross paid out about $7 million before it cut off Pain MD, Wallace said.

These kinds of enormous billing allegations are not uncommon in health care fraud cases, in which fraudsters sometimes find a legitimate treatment that insurance will pay for and then overuse it to the point of absurdity, said Don Cochran, a former U.S. attorney for the Middle District of Tennessee.

Tennessee alone has seen fraud allegations for unnecessary billing of urine testing, skin creams, and other injections in just the past decade. Federal authorities have also investigated an alleged fraud scheme involving a Tennessee company and hundreds of thousands of catheters billed to Medicare, according to The Washington Post, citing anonymous sources.

Cochran said the Pain MD case felt especially “nefarious” because it used opioids to make patients play along.

“A scheme where you get Medicare or Medicaid money to provide a medically unnecessary treatment is always going to be out there,” Cochran said. “The opioid piece just gives you a universe of compliant people who are not going to question what you are doing.”

“It was only opioids that made those folks come back,” he said.

The allegations against Pain MD became public in 2018 when Cochran and the Department of Justice filed a civil lawsuit against the company, Kestner, and several associated clinics, alleging that Pain MD defrauded taxpayers and government insurance programs by billing for “tendon origin injections” that were “not actually injections into tendons at all.”

Kestner, Pain MD, and several associated clinics have each denied all allegations in that lawsuit, which is ongoing.Scott Kreiner, an expert on spine care and pain medicine who testified at Kestner’s criminal trial, said that true tendon origin injections (or TOIs) typically are used to treat inflamed joints, like the condition known as “tennis elbow,” by injecting steroids or platelet-rich plasma into a tendon. Kreiner said most patients need only one shot at a time, according to the transcript.

But Pain MD made repeated injections into patients’ backs that contained only lidocaine or Marcaine, which are anesthetic medications that cause numbness for mere hours, Kreiner testified. Pain MD also used needles that were often too short to reach back tendons, Kreiner said, and there was no imaging technology used to aim the needle anyway. Kreiner said he didn’t find any injections in Pain MD’s records that appeared medically necessary, and even if they had been, no one could need so many.

“I simply cannot fathom a scenario where the sheer quantity of TOIs that I observed in the patient records would ever be medically necessary,” Kreiner said, according to the trial transcript. “This is not even a close call.”

Jonathan White, a physician assistant who administered injections at Pain MD and trained other employees to do so, then later testified against Kestner as part of a plea deal, said at trial that he believed Pain MD’s injection technique was based on a “cadaveric investigation.”

According to the trial transcript, White said that while working at Pain MD he realized he could find no medical research that supported performing tendon origin injections on patients’ backs instead of their joints. When he asked if Pain MD had any such research, White said, an employee responded with a two-paragraph letter from a Tennessee anatomy professor — not a medical doctor — that said it was possible to reach the region of back tendons in a cadaver by injecting “within two fingerbreadths” of the spine. This process was “exactly the procedure” that was taught at Pain MD, White said.

During his own testimony, Kreiner said it was “potentially dangerous” to inject a patient as described in the letter, which should not have been used to justify medical care.

“This was done on a dead person,” Kreiner said, according to the trial transcript. “So the letter says nothing about how effective the treatment is.”

Over-Injecting ‘Killed My Hand’

Pain MD collapsed into bankruptcy in 2019, leaving some patients unable to get new prescriptions because their medical records were stuck in locked storage units, according to federal court records.

At the time, Pain MD defended the injections and its practice of discharging patients who declined the shots. When a former patient publicly accused the company of treating his back “like a dartboard,” Pain MD filed a defamation lawsuit, then dropped the suit about a month later.

“These are interventional clinics, so that’s what they offer,” Jay Bowen, a then-attorney for Pain MD, told The Tennessean newspaper in 2019. “If you don’t want to consider acupuncture, don’t go to an acupuncture clinic. If you don’t want to buy shoes, don’t go to a shoe store.”

Kestner’s trial told another story. According to the trial transcript, eight former Pain MD medical providers testified that the driving force behind Pain MD’s injections was Kestner himself, who is not a medical professional and yet regularly pressured employees to give more shots.

One nurse practitioner testified that she received emails “every single workday” pushing for more injections. Others said Kestner openly ranked employees by their injection rates, and implied that those who ranked low might be fired.

“He told me that if I had to feed my family based on my productivity, that they would starve,” testified Amanda Fryer, a nurse practitioner who was not charged with any crime.

Brian Richey, a former Pain MD nurse practitioner who at times led the company’s injection rankings, and has since taken a plea deal that required him to testify in court, said at the trial that he “performed so many injections” that his hand became chronically inflamed and required surgery.

“‘Over injecting killed my hand,’” Richey said on the witness stand, reading a text message he sent to another Pain MD employee in 2017, according to the trial transcript. “‘I was in so much pain Injecting people that didnt want it but took it to stay a patient.’”

“Why would they want to stay there?” a prosecutor asked.

“To keep getting their narcotics,” Richey responded, according to the trial transcript.

Throughout the trial, defense attorney Peter Strianse argued that Pain MD’s focus on injections was a result of Kestner’s “obsession” with ensuring that the company “would never be called a pill mill.”

Strianse said that Kestner “stayed up at night worrying” about patients coming to clinics only to get opioid prescriptions, so he pushed his employees to administer injections, too.

“Employers motivating employees is not a crime,” Strianse said at closing arguments, according to the court transcript. “We get pushed every day to perform. It’s not fraud; it’s a fact of life.”

Prosecutors insisted that this defense rang hollow. During the trial, former employees had testified that most patients’ opioid dosages remained steady or increased while at Pain MD, and that the clinics did not taper off the painkillers no matter how many injections were given.

“Giving them injections does not fix the pill mill problem,” federal prosecutor Katherine Payerle said during closing arguments, according to the trial transcript. “The way to fix being a pill mill is to stop giving the drugs or taper the drugs.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).