In a Broken Mental Health System, a Tiny Jail Cell Becomes an Institution of Last Resort

POLSON, Mont. — When someone accused of a crime in this small northwestern Montana town needs mental health care, chances are they’ll be locked in a basement jail cell the size of a walk-in closet. Prisoners, some held in this isolation cell for months, have […]

Rural Health

Trump Administration Retreats From 100% Withholding on Social Security Clawbacks

The Social Security Administration is backing off a plan it announced in March to withhold 100% of many beneficiaries’ monthly payments to claw back money the government had allegedly overpaid them. Instead, the agency will default to withholding 50% of old-age, survivors, and disability insurance […]

Health Care

When Hospitals Ditch Medicare Advantage Plans, Thousands of Members Get To Leave, Too

For several years, Fred Neary had been seeing five doctors at the Baylor Scott & White Health system, whose 52 hospitals serve central and northern Texas, including Neary’s home in Dallas. But in October, his Humana Medicare Advantage plan — an alternative to government-run Medicare […]

Health Care

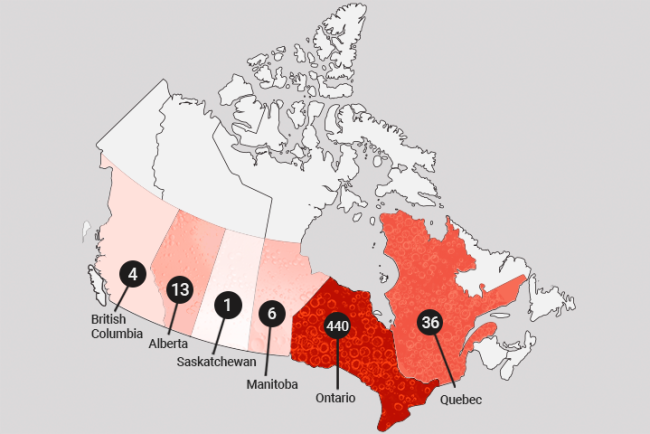

Ontario measles case count rises by a 100 in just a week, total reaches 572

Public Health Ontario is now reporting 572 confirmed and suspected cases since the outbreak began in October. That’s an increase of 102 cases since March 20.

MeaslesPublic Health Ontario is now reporting 572 confirmed and suspected cases since the outbreak began in October. That’s an increase of 102 cases since March 20.

With Few Dentists and Fluoride Under Siege, Rural America Risks New Surge of Tooth Decay

In the wooded highlands of northern Arkansas, where small towns have few dentists, water officials who serve more than 20,000 people have for more than a decade openly defied state law by refusing to add fluoride to the drinking water. For its refusal, the Ozark […]

Health CareIn the wooded highlands of northern Arkansas, where small towns have few dentists, water officials who serve more than 20,000 people have for more than a decade openly defied state law by refusing to add fluoride to the drinking water.

For its refusal, the Ozark Mountain Regional Public Water Authority has received hundreds of state fines amounting to about $130,000, which are stuffed in a cardboard box and left unpaid, said Andy Anderson, who is opposed to fluoridation and has led the water system for nearly two decades.

This Ozark region is among hundreds of rural American communities that face a one-two punch to oral health: a dire shortage of dentists and a lack of fluoridated drinking water, which is widely viewed among dentists as one of the most effective tools to prevent tooth decay. But as the anti-fluoride movement builds unprecedented momentum, it may turn out that the Ozarks were not behind the times after all.

“We will eventually win,” Anderson said. “We will be vindicated.”

Fluoride, a naturally occurring mineral, keeps teeth strong when added to drinking water, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Dental Association. But the anti-fluoride movement has been energized since a government report last summer found a possible link between lower IQ in children and consuming amounts of fluoride that are higher than what is recommended in American drinking water. Dozens of communities have decided to stop fluoridating in recent months, and state officials in Florida and Texas have urged their water systems to do the same. Utah is poised to become the first state to ban it in tap water.

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who has long espoused fringe health theories, has called fluoride an “industrial waste” and “dangerous neurotoxin” and said the Trump administration will recommend it be removed from all public drinking water.

Separately, Republican efforts to extend tax cuts and shrink federal spending may squeeze Medicaid, which could deepen existing shortages of dentists in rural areas where many residents depend on the federal insurance program for whatever dental care they can find.

Dental experts warn that the simultaneous erosion of Medicaid and fluoridation could exacerbate a crisis of rural oral health and reverse decades of progress against tooth decay, particularly for children and those who rarely see a dentist.

“If you have folks with little access to professional care and no access to water fluoridation,” said Steven Levy, a dentist and leading fluoride researcher at the University of Iowa, “then they are missing two of the big pillars of how to keep healthy for a lifetime.”

Many already are.

Overlapping ‘Dental Deserts’ and Fluoride-Free Zones

Nearly 25 million Americans live in areas without enough dentists — more than twice as many as prior estimates by the federal government — according to a recent study from Harvard University that measured U.S. “dental deserts” with more depth and precision than before.

Hawazin Elani, a Harvard dentist and epidemiologist who co-authored the study, found that many shortage areas are rural and poor, and depend heavily on Medicaid. But many dentists do not accept Medicaid because payments can be low, Elani said.

The ADA has estimated that only a third of dentists treat patients on Medicaid.

“I suspect this situation is much worse for Medicaid beneficiaries,” Elani said. “If you have Medicaid and your nearest dentists do not accept it, then you will likely have to go to the third, or fourth, or the fifth.”

The Harvard study identified over 780 counties where more than half of the residents live in a shortage area. Of those counties, at least 230 also have mostly or completely unfluoridated public drinking water, according to a KFF analysis of fluoride data published by the CDC. That means people in these areas who can’t find a dentist also do not get protection for their teeth from their tap water.

The KFF Health News analysis does not cover the entire nation because it does not include private wells and 13 states do not submit fluoride data to the CDC. But among those that do, most counties with a shortage of dentists and unfluoridated water are in the south-central U.S., in a cluster that stretches from Texas to the Florida Panhandle and up into Kansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma.

In the center of that cluster is the Ozark Mountain Regional Public Water Authority, which serves the Arkansas counties of Boone, Marion, Newton, and Searcy. It has refused to add fluoride ever since Arkansas enacted a statewide mandate in 2011. After weekly fines began in 2016, the water system unsuccessfully challenged the fluoride mandate in state court, then lost again on appeal.

Anderson, who has chaired the water system’s board since 2007, said he would like to challenge the fluoride mandate in court again and would argue the case himself if necessary. In a phone interview, Anderson said he believes that fluoride can hamper the brain and body to the point of making people “get fat and lazy.”

“So if you go out in the streets these days, walk down the streets, you’ll see lots of fat people wearing their pajamas out in public,” he said.

Nearby in the tiny, no-stoplight community of Leslie, Arkansas, which gets water from the Ozark system, the only dentist in town operates out of a one-man clinic tucked in the back of an antique store. Hand-painted lettering on the store window advertises a “pretty good dentist.”

James Flanagin, a third-generation dentist who opened this clinic three years ago, said he was drawn to Leslie by the quaint charms and friendly smiles of small-town life. But those same smiles also reveal the unmistakable consequences of refusing to fluoridate, he said.

“There is no doubt that there is more dental decay here than there would otherwise be,” he said. “You are going to have more decay if your water is not fluoridated. That’s just a fact.”

Fluoride Seen as a Great Public Health Achievement

Fluoride was first added to public water in an American city in 1945 and spread to half of the U.S. population by 1980, according to the CDC. Because of “the dramatic decline” in cavities that followed, in 1999 the CDC dubbed fluoridation as one of 10 great public health achievements of the 20th century.

Currently more than 70% of the U.S. population on public water systems get fluoridated water, with a recommended concentration of 0.7 milligrams per liter, or about three drops in a 55-gallon barrel, according to the CDC.

Fluoride is also present in modern toothpaste, mouthwash, dental varnish, and some food and drinks — like raisins, potatoes, oatmeal, coffee, and black tea. But several dental experts said these products do not reliably reach as many low-income families as drinking water, which has an additional benefit over toothpaste of strengthening children’s teeth from within as they grow.

Two recent polls have found that the largest share of Americans support fluoridation, but a sizable minority does not. Polls from Axios/Ipsos and AP-NORC found that 48% and 40% of respondents wanted to keep fluoride in public water supplies, while 29% and 26% supported its removal.

Chelsea Fosse, an expert on oral health policy at the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, said she worried that misguided fears of fluoride would cause many people to stop using fluoridated toothpaste and varnish just as Medicaid cuts made it harder to see a dentist.

The combination, she said, could be “devastating.”

“It will be visibly apparent what this does to the prevalence of tooth decay,” Fosse said. “If we get rid of water fluoridation, if we make Medicaid cuts, and if we don’t support providers in locating and serving the highest-need populations, I truly don’t know what we will do.”

Multiple peer-reviewed studies have shown what ending water fluoridation could look like. In the past few years, studies of cities in Alaska and Canada have shown that communities that stopped fluoridation saw significant increases in children’s cavities when compared with similar cities that did not. A 2024 study from Israel reported a “two-fold increase” in dental treatments for kids within five years after the country stopped fluoridating in 2014.

Despite the benefits of fluoridation, it has been fiercely opposed by some since its inception, said Catherine Hayes, a Harvard dental expert who advises the American Dental Association on fluoride and has studied its use for three decades.

Fluoridation was initially smeared as a communist plot against America, Hayes said, and then later fears arose of possible links to cancer, which were refuted through extensive scientific research. In the ’80s, hysteria fueled fears of fluoride causing AIDS, which was “ludicrous,” Hayes said.

More recently, the anti-fluoride movement seized on international research that suggests high levels of fluoride can hinder children’s brain development and has been boosted by high-profile legal and political victories.

Last August, a hotly debated report from the National Institutes of Health’s National Toxicology Program found “with moderate confidence” that exposure to levels of fluoride that are higher than what is present in American drinking water is associated with lower IQ in children. The report was based on an analysis of 74 studies conducted in other countries, most of which were considered “low quality” and involved exposure of at least 1.5 milligrams of fluoride per liter of water — or more than twice the U.S. recommendation — according to the program.

The following month, in a long-simmering lawsuit filed by fluoride opponents, a federal judge in California said the possible link between fluoride and lowered IQ was too risky to ignore, then ordered the federal Environmental Protection Agency to take nonspecified steps to lower that risk. The EPA started to appeal this ruling in the final days of the Biden administration, but the Trump administration could reverse course.

The EPA and Department of Justice declined to comment. The White House and Department of Health and Human Services did not respond to questions about fluoride.

Despite the National Toxicology Program’s report, Hayes said, no association has been shown to date between lowered IQ and the amount of fluoride actually present in most Americans’ water. The court ruling may prompt additional research conducted in the U.S., Hayes said, which she hoped would finally put the campaign against fluoride to rest.

“It’s one of the great mysteries of my career, what sustains it,” Hayes said. “What concerns me is that there’s some belief amongst some members of the public — and some of our policymakers — that there is some truth to this.”

Not all experts were so dismissive of the toxicology program’s report. Bruce Lanphear, a children’s health researcher at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, published an editorial in January that said the findings should prompt health organizations “to reassess the risks and benefits of fluoride, particularly for pregnant women and infants.”

“The people who are proposing fluoridation need to now prove it’s safe,” Lanphear told NPR in January. “That’s what this study does. It shifts the burden of proof — or it should.”

Cities and States Rethink Fluoride

At least 14 states so far this year have considered or are considering bills that would lift fluoride mandates or prohibit fluoride in drinking water altogether. In February, Utah lawmakers passed the nation’s first ban, which Republican Gov. Spencer Cox told ABC4 Utah he intends to sign. And both Florida Surgeon General Joseph Ladapo and Texas Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller have called for their respective states to end fluoridation.

“I don’t want Big Brother telling me what to do,” Miller told The Dallas Morning News in February. “Government has forced this on us for too long.”

Additionally, dozens of cities and counties have decided to stop fluoridation in the past six months — including at least 16 communities in Florida with a combined population of more than 1.6 million — according to news reports and the Fluoride Action Network, an anti-fluoride group.

Stuart Cooper, executive director of that group, said the movement’s unprecedented momentum would be further supercharged if Kennedy and the Trump administration follow through on a recommendation against fluoride.

Cooper predicted that most U.S. communities will have stopped fluoridating within years.

“I think what you are seeing in Florida, where every community is falling like dominoes, is going to now happen in the United States,” he said. “I think we’re seeing the absolute end of it.”

If Cooper’s prediction is right, Hayes said, widespread decay would be visible within years. Kids’ teeth will rot in their mouths, she said, even though “we know how to completely prevent it.”

“It’s unnecessary pain and suffering,” Hayes said. “If you go into any children’s hospital across this country, you’ll see a waiting list of kids to get into the operating room to get their teeth fixed because they have severe decay because they haven’t had access to either fluoridated water or other types of fluoride. Unfortunately, that’s just going to get worse.”

Methodology: How We Counted

This KFF Health News article identifies communities with an elevated risk of tooth decay by combining data on areas with dentist shortages and unfluoridated drinking water. Our analysis merged Harvard University research on dentist-shortage areas with large datasets on public water systems published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.The Harvard research determined that nearly 25 million Americans live in dentist-shortage areas that span much of rural America. The CDC data details the populations served and fluoridation status of more than 38,000 public water systems in 37 states. We classified counties as having elevated risk of tooth decay if they met three criteria:More than half of the residents live in a dentist-shortage area identified by Harvard.The number of people receiving unfluoridated water from water systems based in that county amounts to more than half of the county’s population.The number of people receiving unfluoridated water from water systems based in that county amounts to at least half of the total population of all water systems based in that county, even if those systems reached beyond the county borders, which many do.

Our analysis identified approximately 230 counties that meet these criteria, meaning they have both a dire shortage of dentists and largely unfluoridated drinking water.

But this total is certainly an undercount. Thirteen states do not report water system data to the CDC, and the agency data does not include private wells, most of which are unfluoridated.

KFF Health News data editor Holly K. Hacker contributed to this article.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Con pocos dentistas y el flúor en el banquillo, zonas rurales corren el riesgo de una nueva oleada de caries

En las tierras altas boscosas del norte de Arkansas, donde los pueblos pequeños tienen pocos dentistas, los funcionarios del agua que atienden a más de 20.000 personas han desafiado abiertamente la ley estatal durante más de una década al negarse a aregar flúor al agua […]

Health CareEn las tierras altas boscosas del norte de Arkansas, donde los pueblos pequeños tienen pocos dentistas, los funcionarios del agua que atienden a más de 20.000 personas han desafiado abiertamente la ley estatal durante más de una década al negarse a aregar flúor al agua potable.

Por su negativa, la Ozark Mountain Regional Public Water Authority ha recibido cientos de multas estatales por un valor aproximado de $130.000, que se guardan en una caja de cartón y no se pagan, según Andy Anderson, quien se opone a la fluoración y ha dirigido el sistema de agua durante casi dos décadas.

Esta región de Ozark se encuentra entre cientos de comunidades rurales estadounidenses que enfrentan un doble golpe para la salud bucal: una grave escasez de dentistas y la falta de agua potable fluorada, considerada ampliamente por los dentistas como una de las herramientas más efectivas para prevenir la caries.

Pero a medida que el movimiento contra el flúor cobra un impulso sin precedentes, podría resultar que los habitantes de Ozark no se quedaron atrás después de todo.

“Al final ganaremos”, dijo Anderson. “Seremos reivindicados”.

El flúor, un mineral natural, mantiene los dientes fuertes cuando se añade al agua potable, según los Centros para el Control y Prevención de Enfermedades (CDC) y la Asociación Dental Americana (ADA). Sin embargo, el movimiento antiflúor se ha revitalizado desde que un informe gubernamental del verano pasado descubrió una posible relación entre un coeficiente intelectual más bajo en niños y el consumo de cantidades de flúor superiores a las recomendadas en el agua potable estadounidense.

Decenas de comunidades han decidido dejar de fluorar su agua en los últimos meses, y las autoridades estatales de Florida y Texas han instado a sus sistemas de agua a hacer lo mismo. Utah está a punto de convertirse en el primer estado en prohibir el flúor en el agua del grifo.

El secretario de Salud y Servicios Humanos, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., quien desde hace tiempo ha defendido teorías alternativas sobre la salud, ha calificado el flúor de “residuo industrial” y “neurotoxina peligrosa” y ha afirmado que la administración Trump recomendará su eliminación del agua potable pública.

Por otra parte, los esfuerzos republicanos por extender los recortes de impuestos y reducir el gasto federal podrían afectar negativamente a Medicaid, lo que podría agravar la escasez de dentistas en las zonas rurales, donde muchos residentes dependen del programa federal de seguros para cualquier tipo de atención dental.

Los expertos en odontología advierten que la erosión simultánea de Medicaid y la fluoración podría exacerbar una crisis de salud bucal rural y revertir décadas de progreso contra la caries dental, especialmente en niños y personas que rara vez van al dentista.

“Si las personas tienen poco acceso a atención profesional y no tienen acceso a la fluoración del agua, entonces están perdiendo dos de los pilares fundamentales para mantenerse saludables de por vida”, afirmó Steven Levy, dentista e investigador líder en fluoruro en la Universidad de Iowa.

Muchos ya los han perdido.

Doble crisis: desiertos dentales y “libres de flúor”

Casi 25 millones de estadounidenses viven en zonas sin suficientes dentistas —más del doble de lo que estimaba el gobierno federal— según un estudio reciente de la Universidad de Harvard que midió los “desiertos dentales” del país con mayor profundidad y precisión que antes.

Hawazin Elani, dentista y epidemióloga de Harvard, coautora del estudio, descubrió que muchas zonas con escasez son rurales y pobres, y dependen en gran medida de Medicaid. Pero muchos dentistas no aceptan Medicaid porque los pagos pueden ser bajos, dijo Elani.

La ADA ha estimado que solo un tercio de los dentistas atienden a pacientes con Medicaid.

“Sospecho que esta situación es mucho peor para los beneficiarios de Medicaid”, dijo Elani. “Si tienes Medicaid y tu dentista más cercano no lo acepta, probablemente tendrás que ir al tercero, cuarto o quinto”.

El estudio de Harvard identificó más de 780 condados donde más de la mitad de los residentes viven en una zona con escasez de agua. De esos condados, al menos 230 también tienen agua potable pública sin fluor, total o en parte, según un análisis de datos de fluoruro de KFF publicado por los CDC. Esto significa que las personas en estas áreas que no pueden encontrar un dentista tampoco obtienen protección para sus dientes con el agua del grifo.

En el centro de este grupo se encuentra la Ozark Mountain Regional Public Water Authority, que presta servicios a los condados de Boone, Marion, Newton y Searcy, en Arkansas. Se ha negado a añadir flúor desde que Arkansas promulgó un mandato estatal en 2011. Tras el inicio de las multas semanales en 2016, el sistema de agua impugnó sin éxito el mandato de flúor en un tribunal estatal, y luego volvió a perder en apelación.

Anderson, quien preside la junta del sistema de agua desde 2007, afirmó que le gustaría impugnar el mandato de flúor de nuevo en los tribunales y que, de ser necesario, presentaría el caso él mismo. En una entrevista telefónica, afirmó creer que el flúor puede perjudicar el cerebro y el cuerpo hasta el punto de hacer que las personas “engorden y se vuelvan perezosas”.

Cerca de allí, en la pequeña comunidad de Leslie, Arkansas, que recibe agua del sistema de Ozark, el único dentista de la ciudad opera en una clínica unipersonal.

Es un dentista escondido en la trastienda de una tienda de antigüedades. Unas letras pintadas a mano en el escaparate anuncian un “buen dentista”.

James Flanagin, dentista de tercera generación que abrió esta clínica hace tres años, comentó que se sintió atraído por Leslie por el encanto pintoresco y las sonrisas amables de la vida de pueblo. Pero esas mismas sonrisas también revelan las inconfundibles consecuencias de negarse a fluorar, afirmó.

“No cabe duda de que aquí hay más caries de las que habría en otras circunstancias”, afirmó. “Vas a tener más caries si tu agua no está fluorada. Es un hecho”.

El flúor, un gran logro de la salud pública

El flúor se agregó por primera vez al agua pública en una ciudad estadounidense en 1945 y, para 1980, se había extendido a la mitad de la población del país, según los CDC. Debido a la drástica disminución de las caries que se produjo posteriormente, en 1999 los CDC clasificaron la fluoración como uno de los 10 grandes logros de salud pública del siglo XX.

Actualmente, más del 70 % de la población estadounidense que utiliza sistemas públicos de agua recibe agua fluorada, con una concentración recomendada de 0,7 miligramos por litro, o aproximadamente tres gotas en un barril de 55 galones, según los CDC.

El flúor también está presente en la pasta de dientes moderna, el enjuague bucal, el barniz dental y algunos alimentos y bebidas, como las pasas, las papas, la avena, el café y el té negro. Sin embargo, varios expertos dentales afirmaron que estos productos no llegan de forma fiable a tantas familias de bajos ingresos como el agua potable, que tiene el beneficio adicional, en comparación con la pasta de dientes, de fortalecer los dientes de los niños desde dentro a medida que crecen.

Dos encuestas recientes han revelado que la mayor parte de los estadounidenses apoya la fluoración, pero una minoría considerable no lo hace. Encuestas de Axios/Ipsos y AP-NORC revelaron que el 48% y el 40% de los encuestados deseaban mantener el flúor en el suministro público de agua, mientras que el 29% y el 26% apoyaban eliminarlo.

Chelsea Fosse, experta en políticas de salud bucal de la American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, expresó su preocupación por el temor injustificado al flúor, que podría llevar a muchas personas a dejar de usar pasta dental y esmalte fluorados, justo cuando los recortes a Medicaid dificultan la consulta con el dentista.

Esta combinación, afirmó, podría ser devastadora.

“Será evidente el impacto que esto tiene en la prevalencia de la caries dental”, declaró Fosse. “Si eliminamos la fluoración del agua, si recortamos Medicaid y si no apoyamos a los proveedores para que identifiquen y atiendan a las poblaciones más necesitadas, realmente no sé qué haremos”.

Múltiples estudios han demostrado cómo podría ser la eliminación de la flúor del agua. En los últimos años, estudios realizados en ciudades de Alaska y Canadá han demostrado que las comunidades que suspendieron la fluoración experimentaron aumentos significativos en la incidencia de caries en niños, en comparación con ciudades similares que no lo hicieron.

Un estudio realizado en 2024 en Israel reportó un aumento del doble en los tratamientos dentales para niños en los cinco años posteriores a la suspensión de la fluoración en el país en 2014.

A pesar de los beneficios de la fluoración, algunos se han opuesto ferozmente desde su inicio, según Catherine Hayes, experta dental de Harvard que asesora a la Asociación Dental Americana sobre el flúor y ha estudiado su uso durante tres décadas.

Inicialmente, la fluoración se desprestigió como un complot comunista contra Estados Unidos, dijo Hayes, y posteriormente surgieron temores de posibles vínculos con el cáncer, que fueron refutados mediante una extensa investigación científica.

En la década de 1980, la histeria alimentó el temor de que el flúor causara sida, lo cual era “absurdo”, dijo Hayes. Más recientemente, el movimiento antiflúor se aprovechó de investigaciones internacionales que sugieren que los altos niveles de flúor pueden obstaculizar el desarrollo cerebral infantil, y se ha visto impulsado por importantes victorias legales y políticas.

En agosto pasado, un informe muy debatido del Programa Nacional de Toxicología de los Institutos Nacionales de la Salud concluyó, con “un nivel de confianza moderado”, que la exposición a niveles de flúor superiores a los presentes en el agua potable estadounidense se asocia con un coeficiente intelectual más bajo en los niños.

El informe se basó en un análisis de 74 estudios realizados en otros países, la mayoría de los cuales se consideraron de “baja calidad” e implicaron una exposición de al menos 1,5 miligramos de flúor por litro de agua —más del doble de la recomendación estadounidense—, según el programa.

Al mes siguiente, en una demanda de larga data presentada por opositores al flúor, un juez federal de California declaró que el posible vínculo entre el flúor y un coeficiente intelectual más bajo era demasiado arriesgado como para ignorarlo, y ordenó a la Agencia de Protección Ambiental (EPA) federal que tomara medidas no especificadas para reducir ese riesgo.

La EPA comenzó a apelar este fallo en los últimos días de la administración Biden, pero la administración Trump podría revertir su postura.

La EPA y el Departamento de Justicia declinaron hacer comentarios. La Casa Blanca y el Departamento de Salud y Servicios Humanos no respondieron a las preguntas sobre el fluoruro.

A pesar del informe del Programa Nacional de Toxicología, Hayes afirmó que, hasta la fecha, no se ha demostrado una asociación entre un coeficiente intelectual bajo y la cantidad de fluoruro presente en el agua de la mayoría de los estadounidenses. El fallo judicial podría impulsar investigaciones adicionales en el país. Hayes espera que finalmente pongan fin a la campaña contra el flúor.

“Es uno de los grandes misterios de mi carrera, qué la sustenta”, declaró Hayes. “Lo que me preocupa es que algunos miembros del público, y algunos de nuestros legisladores, creen que hay algo de cierto en esto”.

No todos los expertos desestimaron el informe del programa de toxicología. Bruce Lanphear, investigador de salud infantil de la Universidad Simon Fraser en Columbia Británica, publicó un editorial en enero que afirmaba que los hallazgos deberían impulsar a las organizaciones sanitarias a “reevaluar los riesgos y beneficios del flúor, especialmente para las mujeres embarazadas y los bebés”.

“Quienes proponen la fluoración ahora deben demostrar que es segura”, declaró Lanphear a NPR en enero. “Eso es lo que hace este estudio: desplaza la carga de la prueba, o debería”.

Ciudades y estados reconsideran el flúor

En lo que va del año, al menos 14 estados han considerado o están considerando proyectos de ley que levantarían los mandatos de flúor o prohibirían por completo el flúor en el agua potable.

En febrero, los legisladores de Utah aprobaron la primera prohibición del país. El gobernador republicano Spencer Cox le dijo a ABC4 que planea firmarla. Tanto el director general de servicios de salud de Florida, Joseph Ladapo, como el comisionado de agricultura de Texas, Sid Miller, han instado a sus respectivos estados a poner fin a la fluoración.

“No quiero que el ‘Gran Hermano’ me diga qué hacer”, declaró Miller a The Dallas Morning News en febrero. “El gobierno nos ha impuesto esto durante demasiado tiempo”.

Además, decenas de ciudades y condados han decidido suspender la fluoración en los últimos seis meses, incluyendo al menos 16 comunidades de Florida con una población combinada de más de 1.6 millones, según informes de prensa y la Red de Acción contra el Flúor.

Stuart Cooper, director ejecutivo de ese grupo, afirmó que el impulso sin precedentes del movimiento sería más fuerte si Kennedy y la administración Trump cumplen con la recomendación contra el flúor.

Cooper predijo que la mayoría de las comunidades estadounidenses dejarán de fluora su agua en unos años.

“Creo que lo que se está viendo en Florida, donde todas las comunidades se desmoronan como fichas de dominó, ocurrirá ahora en Estados Unidos”, afirmó. “Creo que estamos presenciando su fin absoluto”.

Si la predicción de Cooper es correcta, afirmó Hayes, la caries generalizada sería visible en unos años. Los dientes de los niños se pudrirán, agregó, aunque “sabemos cómo prevenirlo por completo”.

“Es un dolor y un sufrimiento innecesarios”, afirmó Hayes. “Si se va a cualquier hospital infantil del país, se verá una lista de espera de niños para entrar al quirófano y que les arreglen los dientes porque tienen caries graves por no haber tenido acceso ni al agua fluorada ni a otros tipos de flúor. Desafortunadamente, esto solo va a empeorar”.

La editora de datos de KFF Health News, Holly K. Hacker, contribuyó con este artículo.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Montana Examines Ways To Ease Health Care Workforce Shortages

HELENA, Mont. — Mark Nay’s first client had lost the van she was living in and was struggling with substance use and medical conditions that had led to multiple emergency room visits. Nay helped her apply for Medicaid and food assistance and obtain copies of […]

Rural HealthHELENA, Mont. — Mark Nay’s first client had lost the van she was living in and was struggling with substance use and medical conditions that had led to multiple emergency room visits.

Nay helped her apply for Medicaid and food assistance and obtain copies of her birth certificate and other identification documents needed to apply for housing assistance. He also advocated for her in the housing process and in the health care system, helping her find a provider and get to appointments.

After a year of “steady engagement,” Nay said, the client has a place to live, is insured, is connected to the health care system, and has the resources needed to “really start to be successful and stable” in her life.

Nay is one of two community health workers in a program that St. Peter’s Health of Helena started in 2022, focusing on people experiencing or at risk of homelessness who had five or more ER visits in a year. Nay and his colleague, Colette Murley, link their clients to services to meet basic needs, whether it’s health care, food, housing, or insurance. The goal is to provide stability and, ultimately, to improve health outcomes.

Similar work is done in hospitals, community health centers, and other settings across Montana by people with titles such as case manager, outreach worker, navigator, and care manager. State Rep. Ed Buttrey, a Great Falls Republican, is sponsoring a bill in Montana’s legislative session to put a common title — community health worker — to the type of work they do and define in law what the role entails. The bill also would provide for licensure and allow, but not require, Medicaid to cover the service.

“Health care is just a very difficult system to navigate, especially when you’re trying to sign up for service and you’re trying to get access to coverage for service,” Buttrey said. “So that’s where I see the biggest benefit.”

Buttrey’s HB 850 is one of several bills still alive this session that are related to Montana’s health care workforce, which is stretched thin throughout the state, the fourth-largest by land area. According to the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration, more than one-fourth of the state’s residents live in an area with a shortage of primary care health professionals.

Other pending workforce bills include three interstate compact bills, to recognize licenses issued in other states for physician assistants, psychologists, and respiratory therapists. Then there are bills to prohibit noncompete clauses for physicians and some categories of mid-level practitioners. Other measures would allow more unsupervised activities by certain aides and assistants, let nurses provide low-cost home visits to low-income patients, allow licensure of doulas, and let physician assistants and physical therapists be considered “treating physicians” for workers’ compensation purposes.

State Rep. Jodee Etchart, a Billings Republican and a physician assistant, is sponsoring two of the interstate compact licensure bills and one of the bills to limit noncompete clauses.

Etchart termed the compact bills “a no-brainer” because they allow people to get licensed, get a job, and start working in Montana right away.

In 2023, Etchart sponsored successful bills to allow physician assistants to practice without physician supervision and to expand the scope of practice for direct-entry midwives. Those bills, she said, helped pave the way for the progress this year’s workforce bills have made this session.

“It opened a lot of people’s eyes about how we can increase access to health care all over Montana,” she said.

The 2023 bill allowing independent practice by physician assistants drew opposition from physicians, with the Montana Medical Association saying it extended their scope of practice without requiring additional training. This session, the MMA has supported the bills to remove noncompete provisions but opposed bills on expanding the scope of practice for chiropractors and optometrists. MMA CEO Jean Branscum said the group generally believes scope-of-practice changes don’t fix workforce problems if the expanded practice isn’t supported by evidence or training.

Buttrey said this session’s bills to extend unsupervised practice and enact licensure compacts are an acknowledgment of the difficulty that small, rural communities have in attracting doctors. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners have been filling those gaps, he said.

Community health workers fill a different type of gap. They don’t provide direct medical care, instead helping people find the health care and support services they need to become and remain healthy.

Many states have already adopted definitions for community health workers and started providing Medicaid reimbursement for their services.

The requests to add to the list of Medicaid-covered services come at a time when Congress is considering significant budget cuts that could affect the amount of funding the federal government contributes to the Medicaid program. Although the legislature this session continued Montana’s Medicaid expansion program for low-income adults without disabilities, some legislators expressed concern about potential federal changes that could lower the amount of federal funds available for the program.

State Sen. Carl Glimm, a Kila Republican, was one of those legislators. He said he has similar concerns about increasing the types of services covered by Medicaid.

“The more stuff we add,” he said, “the more responsibility the state has” if the federal government shifts more of the program’s costs to the states.

Buttrey’s bill would define a community health worker as a “frontline public health worker” who helps people obtain medical and social services, advocates for their health, and educates individuals, providers, and the community about health care needs. Workers could be licensed after completing training and supervision requirements.

Most medical providers don’t have time to delve into all the outside factors influencing a patient’s health, said Cindy Stergar, CEO of the Montana Primary Care Association, which is supporting Buttrey’s bill. Community health workers can assist with that, she said, adding that research shows people with complex needs become healthier faster when their basic nonmedical needs, such as food and housing, are met.

“At the end of the day, the patient is better,” Stergar said. “That’s first and foremost.”

The Area Health Education Center at Montana State University has been offering community health worker training since 2018, and the University of Montana’s Center for Children, Families and Workforce Development began a training program in 2023. Together, the programs have trained nearly 500 people in how to identify the medical and social factors influencing a person’s health and in strategies for connecting the person with the right community resources.

“Ideally, what community health workers are doing is getting out of the clinic walls, meeting people where they are, and addressing the priorities of the client to get to the root cause of their health conditions and health needs,” said Mackenzie Petersen, project director for the training program at the University of Montana.

Supporters of the community health worker role say the workers are uniquely positioned to observe, understand, and address the barriers preventing a person from getting and staying healthy.

The barriers might be a lack of transportation or insurance or, for a homeless person, the inability to refrigerate a prescribed medication. A community health worker can arrange rides to appointments, help with insurance applications, or make sure a health care provider prescribes a medication that doesn’t need refrigeration.

Murley, with the St. Peter’s Health program, recalled that one of her clients was making frequent trips to the ER with suicidal ideation. Murley learned that he faced bullying in his apartment building and helped him relocate. The ER visits dropped off.

As Nay put it: “It’s really about helping the people that we work with create a path to their health.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Many People With Disabilities Risk Losing Their Medicaid if They Work Too Much

PLEASANTVILLE, Iowa — Zach Mecham has heard politicians demand that Medicaid recipients work or lose their benefits. He also has run into a jumble of Medicaid rules that effectively prevent many people with disabilities from holding full-time jobs. “Which is it? Do you want us […]

Health CarePLEASANTVILLE, Iowa — Zach Mecham has heard politicians demand that Medicaid recipients work or lose their benefits. He also has run into a jumble of Medicaid rules that effectively prevent many people with disabilities from holding full-time jobs.

“Which is it? Do you want us to work or not?” he said.

Mecham, 31, relies on the public insurance program to pay for services that help him live on his own despite a disability caused by muscular dystrophy. He uses a wheelchair to get around and a portable ventilator to breathe.

A paid assistant stays with Mecham at night. Then a home health aide comes in the morning to help him get out of bed, go to the bathroom, shower, and get dressed for work at his online marketing business. Without the assistance, he would have to shutter his company and move into a nursing home, he said.

Private health insurance plans generally do not cover such support services, so he relies on Medicaid, which is jointly financed by federal and state governments and covers millions of Americans who have low incomes or disabilities.

Like most other states, Iowa has a Medicaid “buy-in program,” which allows people with disabilities to join Medicaid even if their incomes are a bit higher than would typically be permitted. About two-thirds of such programs charge premiums, and most have caps on how much money participants can earn and save.

Some states have raised or eliminated such financial caps for people with disabilities. Mecham has repeatedly traveled to the Iowa Capitol to lobby legislators to follow those states’ lead. The “Work Without Worry” bill would remove income and asset caps and instead require Iowans with disabilities to pay 6% of their incomes as premiums to remain in Medicaid. Those fees would be waived if participants pay premiums for employer-based health insurance, which would help cover standard medical care.

Disability rights advocates say income and asset caps for Medicaid buy-in programs can prevent participants from working full time or accepting promotions. “It’s a trap — a poverty trap,” said Stephen Lieberman, a policy director for the United Spinal Association, which supports the changes.

Lawmakers in Florida, Hawaii, Indiana, Iowa, Maine, Mississippi, and New Jersey have introduced bills to address the issue this year, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Several other states have raised or eliminated their program’s income and asset caps. Iowa’s proposal is modeled on a Tennessee law passed last year, said Josh Turek, a Democratic state representative from Council Bluffs. Turek, who is promoting the Iowa bill, uses a wheelchair and earned two gold medals as a member of the U.S. Paralympics basketball team.

Proponents say allowing people with disabilities to earn more money and still qualify for Medicaid would help ease persistent worker shortages, including in rural areas where the working-age population is shrinking.

Turek believes now is a good time to seek expanded employment rights for people with disabilities, since Republicans who control the state and federal governments have been touting the value of holding a job. “That’s the trumpet I’ve been blowing,” he said with a smile.

The Iowa Legislature has been moving to require many nondisabled Medicaid recipients to work or to document why they can’t. Opponents say most Medicaid recipients who can work already do so, and the critics say work requirements add red tape that is expensive to administer and could lead Medicaid recipients to lose their coverage over paperwork issues.

Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds has made Medicaid work requirements a priority this year. “If you can work, you should. It’s common sense and good policy,” the Republican governor told legislators in January in her “Condition of the State Address.” “Getting back to work can be a lifeline to stability and self-sufficiency.”

Her office did not respond to KFF Health News’ queries about whether Reynolds supports eliminating income and asset caps for Iowa’s buy-in program, known as Medicaid for Employed People with Disabilities.

National disability rights activists say income and asset caps on Medicaid buy-in programs discourage couples from marrying or even pressure them to split up if one or both partners have disabilities. That’s because in many states a spouse’s income and assets are counted when determining eligibility.

In Iowa, for example, the monthly net income cap is $3,138 for a single person and $4,259 for a couple.

Iowa’s current asset cap for a single person in the Medicaid buy-in plan is $12,000. For a couple, that cap rises only to $13,000. Countable assets include investments, bank accounts, and other things that could be easily converted to cash, but not a primary home, vehicle, or household furnishings.

“You have couples who have been married for decades who have to go through what we call a ‘Medicaid divorce,’ just to get access to these supports and services that cannot be covered in any other way,” said Maria Town, president of the American Association of People with Disabilities.

Town said some states, including Massachusetts, have removed income caps for people with disabilities who want to join Medicaid. She said the cost of adding such people to the program is at least partially offset by the premiums they pay for coverage and the increased taxes they contribute because they are allowed to work more hours. “I don’t think it has to be expensive” for the state and federal governments, she said.

Congress has considered a similar proposal to allow people with disabilities to work more hours without losing their Social Security disability benefits, but that bill has not advanced.

Although most states have Medicaid buy-in programs, enrollment is relatively low, said Alice Burns, a Medicaid analyst at KFF, a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

Fewer than 200,000 people nationwide are covered under the options, Burns said. “Awareness of these programs is really limited,” she said, and the income limits and paperwork can dissuade potential participants.

In states that charge premiums for Medicaid buy-in programs, monthly fees can range from $10 to 10% of a person’s income, according to a KFF analysis of 2022 data.

The Iowa proposal to remove income and asset caps has drawn bipartisan backing from legislators, including a 20-0 vote of approval from the House Health and Human Services Committee. “This aligns with things both parties are aiming to do,” said state Rep. Carter Nordman, a Republican who chaired a subcommittee meeting on the bill. Nordman said he supports the idea but wants to see an official estimate of how much it would cost the state to let more people with disabilities participate in the Medicaid buy-in program.

Mecham, the citizen activist lobbying for the Iowa bill, said he hopes it allows him to expand his online marketing and graphic design business, “Zach of All Trades.”

On a recent morning, health aide Courtnie Imler visited Mecham’s modest house in Pleasantville, a town of about 1,700 people in an agricultural region of central Iowa. Imler chatted with Mecham while she used a hoist to lift him out of his wheelchair and onto the toilet. Then she cleaned him up, brushed his hair, and helped him put on jeans and a John Deere T-shirt. She poured him a cup of coffee and put a straw in it so he could drink it on his own, swept the kitchen floor, and wiped the counters. After about an hour, she said goodbye.

After getting cleaned up and dressed, Mecham rolled his motorized wheelchair over to his plain wooden desk, fired up his computer, and began working on a social media video for a client promoting a book. He scrolled back and forth through footage of an interview she’d done, so he could pick the best clip to post online. He also shoots video, takes photos, and writes advertising copy.

Mecham loves feeling productive, and he figures he could work at least twice as many hours if not for the risk of losing Medicaid coverage. He said he’s allowed to make a bit more money than Iowa Medicaid’s standard limit because he signed up for a federal option under which he eventually expects to work his way off Social Security disability payments.

There are several such options for people with disabilities, but they all involve complicated paperwork and frequent reports, he said. “This is such a convoluted system that I have to navigate to build any kind of life for myself,” he said. Many people with disabilities are intimidated by the rules, so they don’t apply, he said. “If you get it wrong, you lose the health care your life depends on.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Bill That Congressman Says Protects Medicaid Doesn’t — And Would Likely Require Cutting It

“On Feb. 25, I voted yes on a budget resolution that protects Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid while cutting some spending elsewhere.” Rep. Nick LaLota (R-N.Y.), in a YouTube video posted March 4, 2025 On Feb. 25, Rep. Nick LaLota (R-N.Y.) voted in favor of […]

Health Care“On Feb. 25, I voted yes on a budget resolution that protects Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid while cutting some spending elsewhere.”

Rep. Nick LaLota (R-N.Y.), in a YouTube video posted March 4, 2025

On Feb. 25, Rep. Nick LaLota (R-N.Y.) voted in favor of a House budget resolution that calls for sharp cuts in spending across a vast array of government areas. Medicaid is among the programs that could be at risk — catapulting it to the center of the political debate.

President Donald Trump has insisted he won’t harm Medicaid, Medicare, and Social Security benefits, saying his administration is looking to root out fraud. But Democrats have pushed back, saying the sheer size of the proposed cuts will result in harm to the Medicaid program, its enrollees, and medical providers.

A KFF tracking poll has found widespread public support for Medicaid, which suggests efforts to cut the program could face political headwinds. KFF is a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

LaLota, who represents part of Long Island, posted a video for his constituents explaining his position: “I voted yes on a budget resolution that protects Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid while cutting some spending elsewhere.” Because much of his video focused on Medicaid, we did too. We found that his statement in this regard was layered with mischaracterizations and inaccuracies. Yet, in his video, LaLota advises his constituents to get their information straight from him, saying, “I’ll always be honest with you.”

We asked LaLota’s office for the information he used to back up his statement. The budget resolution makes no cuts to those programs, he wrote in a statement emailed by his communications aide Mary O’Hara. “Rather, it opens the door to protect Medicaid with common-sense solutions which ensure its availability for those Americans who qualify, including the removal of illegals from the rolls, work requirements for able-bodied adults, and the elimination of waste, fraud, and abuse.”

Let’s parse what the resolution does say and do, and the changes it could trigger for Medicaid.

Explaining the Basics

Budget resolutions are not law, but rather blueprints that guide lawmakers on budget-related legislation. The House-passed resolution — approved with 217 Republicans voting for it and 214 Democrats and one Republican against — is just one part of the budget process. The Senate also has a say, so changes are possible.

As written, the resolution seeks broad spending reductions across a range of areas overseen by various committees. It specifically asks the House Committee on Energy and Commerce to submit proposals “to reduce the deficit by not less than $880,000,000,000 [$880 billion] for the period of fiscal years 2025 through 2034.”

It does not say it would protect Medicaid. The word Medicaid is nowhere in the document. It does not prescribe any specific action on the program, such as instituting work requirements for recipients. Lawmakers separately draft legislation to make program adjustments to achieve the spending cut targets.

A little background: Medicaid is a state-federal program that provides medical coverage to lower-income residents, as well as payments to nursing homes for caring for seniors and disabled residents. Medicaid and the closely related Children’s Health Insurance Program cover more than 79 million people.

Medicare is the federal program that provides health insurance for some disabled people and most people over age 65. More than 68 million people are enrolled.

The resolution directs the committee to draft legislative language that would cut spending from areas under its jurisdiction, which include Medicaid and about half of Medicare.

Social Security is mainly overseen in the House by the Committee on Ways and Means. The panel also shares jurisdiction over Medicare with Energy and Commerce.

Policy experts and the Congressional Budget Office have said that, after removing Medicare from consideration, there’s not enough under the committee’s jurisdiction to cut $880 billion without substantially reducing Medicaid spending. (Medicare is generally considered a third rail because its beneficiaries are a powerful voting bloc.)

Indeed, of the $8.8 trillion in projected spending under the committee’s purview for the 10-year period, Medicaid accounts for $8.2 trillion, or 93%.

“Even if the committee eliminated all of non-Medicare and non-Medicaid spending, they would still have to cut Medicaid by well over $700 billion,” said Alice Burns, an associate director of KFF’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured.

Adding work requirements — most Medicaid recipients already have jobs — would not yield that level of savings and could increase state costs. Other cuts suggested by Republicans, including capping federal spending per enrollee, reducing federal matching dollars, and eliminating the use of provider taxes, which states use to pay for their share of Medicaid spending, could force states to cut spending or find new revenue sources.

“Cuts to Medicaid could mean eliminating coverage for children, parents, working adults or those who might need long term care; limiting benefits; or cutting payment rates for health plans or providers. These choices could come at a time when state revenue growth is slowing, and most states face requirements to pass balanced budgets,” according to an analysis by Robin Rudowitz, vice president of the KFF Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured.

The downstream effects if the House-passed budget resolution were enacted would be wide-ranging and significantly alter the safety net program, said Edwin Park, a research professor at the Center for Children and Families at Georgetown University.

He noted growing opposition to such large-scale Medicaid cuts from “beneficiaries and parents of children with disabilities, families with parents in nursing homes, and from health care providers.”

“Medicaid cuts are highly unpopular even among Trump voters,” he said.

Opposition to Medicaid cuts helped kill the 2017 attempt to repeal the Affordable Care Act during the first Trump administration, noted Joseph Antos, a senior fellow emeritus at the American Enterprise Institute.

Antos thinks the current spending cut target is unrealistic and will likely not survive the effort to merge the House budget blueprint with what the Senate wishes to do.

“Ultimately, the problem is you can’t take that much out of Medicaid,” Antos said.

LaLota’s focus on immigrants lacking legal status as a way to reduce federal spending on Medicaid is also misleading.

A number of states, including New York, offer coverage to children or adults regardless of immigration status, but they can use only state money to pay for such programs.

“States cannot use federal funding to cover undocumented immigrants,” Burns said. So removing them “won’t do anything for the deficit reduction targets.”

Our Ruling

LaLota said, “On Feb. 25, I voted yes on a budget resolution that protects Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid while cutting some spending elsewhere.”

His statement is inaccurate and mischaracterizes laws and the language included in the budget resolution, creating a false impression of what his vote supported.

The 32-word sentence that directs the Energy and Commerce Committee to trim $880 billion over 10 years from programs it authorizes does not include any protections, guardrails, or specific directions for the panel to follow.

We rate this claim False.

Sources:

Rep. Nick LaLota, constituent video, March 4, 2025.

Clerk, United States House of Representatives, “Roll Call 50 | Bill Number H. Con. Res. 14,” Feb. 25, 2025.

Newsweek, “Donald Trump Issues Social Security, Medicaid Update,” March 10, 2025.

Rep. Hakeem Jeffries, press release, March 16, 2025.

KFF, February tracking poll, March 7, 2025.

Medicaid.gov, “October 2024 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights,” accessed March 17, 2025.

Congressional Budget Office, letter to Reps. Brendan Boyle and Frank Pallone, March 5, 2025.

KFF Quick Takes, “As Governors Meet in D.C., Possible Federal Medicaid Cuts Loom as Big State Funding Issue,” Feb. 20, 2025.

KFF, “Key Facts on Health Coverage of Immigrants, Jan. 15, 2025.

Telephone interview with Joseph Antos, senior fellow emeritus, American Enterprise Institute, March 17, 2025.

Telephone interview with Edwin Park, research professor at the Center for Children and Families, Georgetown University, March 17, 2025.

Telephone interview with Alice Burns, associate director, Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, KFF, March 17, 2025.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Ontario measles outbreak linked to New Brunswick Mennonite gathering

Dr. Kieran Moore wrote measles is ‘disproportionately affecting some Mennonite, Amish, and other Anabaptist communities’ because of under-immunization and exposures.

MeaslesDr. Kieran Moore wrote measles is ‘disproportionately affecting some Mennonite, Amish, and other Anabaptist communities’ because of under-immunization and exposures.

Medicaid Cuts Would Kneecap Health Services, Tribal Leaders Warn

While Congress considers potentially massive cuts to federal Medicaid funding, tribal health leaders are bracing for a crisis. Indian Country has a unique relationship to Medicaid, because the program helps tribes cover chronic funding shortfalls left by the Indian Health Service, the federal agency responsible […]

Health CareWhile Congress considers potentially massive cuts to federal Medicaid funding, tribal health leaders are bracing for a crisis.

Indian Country has a unique relationship to Medicaid, because the program helps tribes cover chronic funding shortfalls left by the Indian Health Service, the federal agency responsible for providing health care to Native Americans.

With the related Children’s Health Insurance Program, Medicaid provides coverage to more than a million Native Americans. The joint state-federal program also accounts for about two-thirds of non-IHS revenue for tribal health providers. That income helps create financial stability and covers some operational costs for tribal hospitals and clinics. Tribal leaders want an exemption from any cuts and are preparing for a fight to preserve their access.

“Medicaid is one of the ways in which the federal government meets its trust and treaty obligations to provide health care to us,” said Liz Malerba, director of policy and legislative affairs for the United South and Eastern Tribes Sovereignty Protection Fund, a nonprofit advocacy organization for 33 tribes spanning from Texas to Maine. Malerba is a citizen of the Mohegan Tribe.

“So we view any disruption or cut to Medicaid as an abrogation of that responsibility,” she said.

Last month, the House approved a budget resolution that requires lawmakers to cut spending to offset tax breaks. The House Committee on Energy and Commerce, which oversees spending on Medicaid, is instructed to slash $880 billion over the next decade.

The IHS projects that it will bill Medicaid about $1.3 billion this fiscal year, which represents less than half of 1% of overall federal spending on Medicaid.

If Congress makes big cuts to the program, tribal health facilities will likely need to scale back services for a population that experiences severe health disparities, a high incidence of chronic illness, and a shorter life expectancy.

“When you’re talking about somewhere between 30% to 60% of a facility’s budget is made up by Medicaid dollars, that’s a very difficult hole to try and backfill,” said Winn Davis, congressional relations director for the National Indian Health Board.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Calls for Ford government to do more to tackle growing measles outbreak

On Thursday, Public Health Ontario reported a total of 470 measles cases, up from 120 cases the week before. Thirty-four people were in hospital and two in intensive care.

MeaslesOn Thursday, Public Health Ontario reported a total of 470 measles cases, up from 120 cases the week before. Thirty-four people were in hospital and two in intensive care.

Measles is spreading across Canada. A look at the affected areas

Measles is surging across Canada, alarming health officials as new cases emerge in the Prairies, possibly signaling the westward spread of Ontario’s outbreak.

MeaslesMeasles is surging across Canada, alarming health officials as new cases emerge in the Prairies, possibly signaling the westward spread of Ontario’s outbreak.